Splatoon is my favorite multiplayer shooter series right now. There’s a lot of reasons for that, from the inimitable youthful aesthetic, to the novelty of its premise, to the breadth of self-expression available to players. I think what most draws me back to this game again and again is just how effortlessly it induces the Flow State. The Flow State is a psychological concept that you may have come across by many names in different fields. It is being fully immersed and cognitively absorbed with a task. It is being ‘in the zone’, so to speak. It is associated with a certain energy, a joy, in the act of doing. As applied to games, it’s what happens when you become so involved in with the game, so in sync with its rules and systems that you feel time slip away, when effort becomes so natural it feels like no effort at all. It’s the kind of thing I make games for, as opposed to any other medium, and Splatoon pulls it off beautifully in the way its most basic gameplay is structured.

You’re a Kid Now You’re a Squid Now

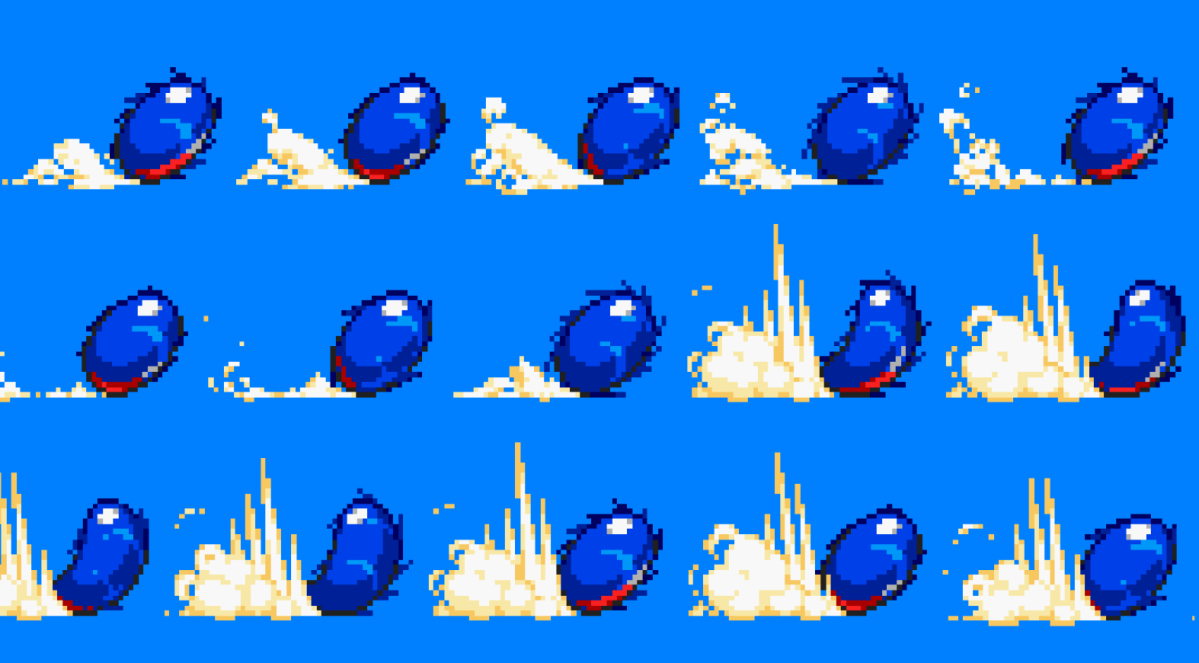

Like many great games Splatoon is a system built on mobility and positioning. However, its breakout idea is that the players have agency not only in how they move, but in what areas of the game space are available to them to move. Most shooters’ main actions are move and shoot. Splatoon adds move, shoot, and claim turf. Your team claims turf on any playable surface they shoot with their ink-based weaponry. At any time, players may shift from their ‘kid’ form, in which they can shoot to claim turf or defeat opponents (‘splat’ them) to their ‘squid’ or ‘swim’ form. In the swim form, shooting is not available as an action, but mobility options are greatly expanded. While swimming, a player is significantly faster on the ground, while also gaining the ability to scale sheer walls that have been claimed by allied ink.

Splatoon has a created an inherent meaningful decisions layered on top of the typical scenario in a competitive shooter. Like in other games, players have the option to take cover, spray suppressive fire, focus down single targets, and the rest, but they also have the omnipresent option to forego offense entirely for the swim form, making them more mobile, and harder to see. The last essential wrinkle is that ammo (ink) is limited, the player can only load so much at one time. To reload, the player needs to swim through allied ink that has already been laid down. This also quickly heals any damage you’ve taken, acting as a catch-all resource renewal action.

Your two modes now create a feedback loop. Shooting can accomplish two things. One: splatting players which gives you and your teammates safe space to advance the game’s main objective, which is usually to claim turf. And two: claiming turf, which is the metric by which the winning team is judged, but also provides a tactical advantage in allied ink’s utility to evasive maneuvers, ambushes, and advantageous positioning. The more angles you have on your opponent, the more limited their options as opposed to yours. Swimming accomplishes two things as well. One: The increased swim speed, decreased visibility, and healing of the swim form makes a swimming player a much less vulnerable target than a shooting one. Two: A swimming player is restoring ammunition, which must be done to continue shooting.

Here Splatoon has through incentives solidified its gameplay loop to where shooting gives you more space for swimming, and swimming enables you to continue shooting. After getting used to the unconventional systems, it quickly becomes intuitive how they relate to each other, and thus players will naturally begin to fall into a pattern, which typically looks like this:

Lay down plentiful amounts of ink to claim turf, including a path to your next desired, probably tactically chosen, location. Then, swim to that location to reload your ink. Engage the enemy team either though frontal assault or ambush tactics, utilizing your own turf for advantage. Whether the enemy is splatted, or you or pushed back, you’ll relocated using your own turf, renewing your resources at the same time, and repeat. Ink and swim, ink and swim.

The Simple Pleasure of Splatter

Splatoon is a crunchy, colorful, game with lush audio-visual feedback. A lot of care was clearly taken to making the act of laying down ink very satisfying. There’s a simple joy in seeing color overtake the environment, permanent marks of your activity. The wild shapes and pathways carved across the terrain, as seen from above in the final score tally screen of each match, leaves evidence of every assault, flank, retreat, and regroup each team took part in.

It is intrinsically motivating to want to just cover stuff in pretty colors. With that desire in place, and the necessity of the swim form for continuing to do that, players are naturally encouraged to tactically engage with the game, and consider their surroundings. No matter what, when you run out of ink, you have to swim for a bit to restore it, so players are given a mandatory bit of space and pause in the action to acknowledge their context. Splatoon trains players to always be considering their next move. You know you have to restore ink, so you know you have to relocate eventually as some ground is ceded to your opponents.

This space to consider is a permanent and mandatory part of the game loop, but is also fun in and of itself. Movement in Splatoon while in kid form isn’t horribly slow, not nearly slow enough to be frustrating, but it is pointedly slower than swimming. The contrast makes swimming through ink exhilarating and liberating. It also makes one feel powerful compared to those not swimming at that exact moment, as a swimming squid has the advantage of wall-scaling and stealth through their reduced visibility. At any moment you can jump out to ambushed an unsuspecting opponent. So while Splatoon is essentially forcing an idealized interested curve through the interplay of its mechanics (moments of high intensity shooting to moments of less intense swimming, reloading, and repositioning), it remains intrinsically motivating throughout.

Through this enforced rhythm and tactical engagement, the endless looping of shoot, swim, ink, shoot, swim becomes natural. Before long, it will feel second-nature to veteran players, like skiing veterans effortlessly gliding back and forth across a slope. Ink, shoot, swim, reposition, shoot, ink, swim, retreat, ink, swim, etc.

I really think its the rhythmic nature of this extreme tight gameplay loop that makes Splatoon so engrossing. In some ways it feels almost like a ritual, meant to teach you the inherent interrelations of Splatoon‘s various modes of interaction. For example, knowing that swimming is the best, fastest way to move, and that it restores your ammo, one might realize that swimming with a full tank of ink is a bit of a waste. That’s ink which could be better spent elsewhere. If you know you’re going to be swimming for a bit to get to your next location, it would be ideal if you could spend a great deal of your ink all at once at something productive. And… wouldn’t you know it, there is such a tool, a secondary weapon all players have access to that consume a large amount of ink, but can claim turf at a great distance, create threatened space to keep enemies away, or even outright splat enemies instantly. Indeed, throwing a splat-bomb secondary weapon into the distance before swimming a ways to restore the sunk cost is a powerful strategy.

Push Buttons and You’re Contributing

One thing I want to briefly touch on is how Splatoon goes out of its way to maintain this rhythm no matter what. After all, the point of Flow is its uninterrupted and focused nature. You know, a flow. Splatoon clearly values this flow state greatly, with all of the contingencies it deploys for possible interruptions. There’s a couple of techniques it uses to do this.

First, death and death timers. Sorry, splatting and respawn timers. When getting splatted, you’re put out of commission for some time. There has to be some reward for getting a splat where shooting the other guy is a primary goal, so some space and time is awarded to the successful splatter-er. However, this game wants as little (boring) downtime as possible, and will thrust a defeated player back into the action as soon as possible. Respawn timers never last more than 10 seconds. Lots of shooters have similar respawn timers, but Splatoon‘s super jump mechanic, which lets players immediately jump to an ally’s location makes getting back into the action incredibly quick and breezy. To counteract this, so that every match doesn’t devolve into an immovable, non-dynamic stalemate, the average TTK or time to kill in Splatoon is very low, meaning just a little bit of forethought or even luck can unseat a skilled opponent who’s caught unawares. If ambushed, a squid kid can be taken down in a fraction of a second.

The inherent risk in attacking in Splatoon is reduced in this way. If you can outmaneuver an opponent you might be able to defeat them before they have a chance to hit you with any reprisal. There’s a synthesis of strategy and instinct here that’s very friendly to newer players. If beating someone in a competition is so demanding that a new player can never get one over on their opponent, the game runs a high risk of bouncing off of them. We want those new players to experience that engrossing flow state uninterrupted, so beating even veteran players in shootouts is made a very attainable goal.

Of course, even if you’re not extremely predisposed to shooting opponents in general, Splatoon‘s got your flow state covered. Simply shooting the unmoving ground beneath your feet creates a tactical advantage for your team. Inking turf is how you build up your special weapon, which itself is quite powerful for creating space, inking turf, and splatting opponents. A note on those special weapons, by the by. If a player is splatted, they lose progress towards charging their special weapon, even if it’s already fully charged! I love this design decision, as it encourages liberal use of the special weapons, which is exciting for both sides of the match. Use them with some strategy, sure, but if you don’t use it for too long, you will most certainly lose it. Why is this good? Well it prevents that boring downtime, where players might be encouraged to play passively, waiting for the perfect moment to throw out a bunch of specials rather than just using them so they can charge up the next one.

Anyway, inking turf is the main goal of most gameplay modes, and it contributes directly to your team’s likelihood of success. It also increases your more violently-minded teammate’s options for splatting opponents. If the enemy team’s hard-hitters are simply hitting too hard for your comfort zone, any player can contribute with minimal risk of interruption if they avoid the front lines, and just focus on getting into that flow of laying ink, swimming, laying ink.

Masahiro Sakurai, creator of the Kirby and Super Smash Bros. series, recently shared his theory that there is a relationship between the level of a game’s ‘Game Essence’ or ‘Risk and Reward’ and the broadness of its appeal to a wider audience. I think there’s some merit to this line of thinking, and the runaway success of Splatoon, which has implemented so many clever ways to diminish inherent risk so as to maintain the integrity of its gameplay loop for all players, winning or losing, while also allowing greater levels of risk for high-skill strategy and gameplay execution, supports it. One of the many reasons for Smash Bros. success, I think, is a philosophy of risk vs. reward similar to Splatoon‘s. In fact, I wouldn’t be surprised if the former were an inspiration to the latter.

Swimming In Splatoon’s Energy

If there’s three words I’d use to describe Splatoon‘s vibe they’d be ‘youthful’, ‘vibrant’ and ‘expressive’. It’s a game that gives so many unique avenues to accomplish it’s primary goals, but all through a highly tuned gameplay loop that encourages situational awareness and engagement to create an engine for inducing the flow state. Splatoon‘s greater context of youth-dominated urban spaces playing host to the world’s coolest city-wide paintball matches encourages an inviting environment of constant partying, and playing the game feels like that too; a nonstop party, three minutes at a time. It’s a lot of little hidden motivators working in tandem behind the scenes that create this overall vibe. It’s amazing the sense of freedom I get from such a precisely controlled set of parameters. When I really get into a match of Splatoon, I hardly feel as though the space between myself and the world of the game exists at all. It’s like swimming in that exciting space. If I could master one aspect of Splatoon‘s design it would be that.

Stay Fresh…