You’ve heard it before. I’ve said it, she’s said it, we’ve all said it – those of us who’ve played it anyway. Paper Mario: The Thousand Year Door is the best Paper Mario game. The best Mario RPG in general, in my humble opinion. That’s pretty astounding for a series that’s been going on for more than two decades. Sure, plenty of people still mark games like Final Fantasy VII and The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time as the best of their respective series, but there have been many more contenders for both since then. Some from as recently as now, more or less (Time of writing: 2023). My point is, rare has a single entry in a series as The Thousand Year Door been so universally beloved, over and above its peers.

I think there’s a lot of reasons. The Thousand Year Door offers a rare interpretation of the bizarre Mario universe in a more grounded and holistic way, with a narrative bent. It introduces new, named characters and puts iconic Mario characters in novel and interesting situations. The world and narrative design went out of its way to be weird, surprising, and gripping in ways the more straightforward Mario games prefer to be safe, familiar, and general-purpose. But that’s not what we’re here to talk about today. Paper Mario: The Thousand Years Door is not only funnier, more dramatic, and more rich with character than every Paper Mario that came after it, it also plays better than every Paper Mario that came after it. The Thousand Year Door has some of the most elegant systems I’ve seen in a video game.

I could ramble for hours about how great Paper Mario: The Thousand Year Door, is but as you’ve no doubt seen many others do so elsewhere, so I will spare you. The focus here is going to be on the gameplay and systems that make the first two entries of Paper Mario so great, even isolated from all other elements. These systems which, in subsequent entries preceding The Thousand Year Door’s 2024 remake like Color Splash, and Origami King, were altered in specific and fascinating ways that had a profound effect on the gameplay of those games.

Oh shoot, wrong image. This is a picture of me remembering I have to write this blog post. How’d that get in there?

Elegance In Design

So what do I mean by elegant? To me, elegance is all about approachability, and applicability. To create an elegant system, you need an interface that is welcoming, intuitive, and easy to understand, which interacts with each game system in ways such to produce an engaging experience. A sentence, to me, elegant design means systems which find depth in simplicity. Simplicity. This is, paradoxically, a rather difficult thing to achieve – systems that appear simplistic yet offer a lot of depth.

The first Paper Mario for the Nintendo 64 tackled this problem by stripping down the turn-based RPG genre to its barest essentials, which I think is often a good step to take when trying to really take stock of the high-level, fundamental building blocks of your game. What about turn-based, party-based RPGs is fun or engaging on a ludic level? The turn part of that formula allows for infinite time to consider decisions. So, high-level, low-stress decision making. Overcoming stronger opponents by utilizing party members’ unique abilities in combination, feeling clever. Customizing character loadout for unique abilities to reflect individual playstyles. Collecting rewards when defeating strong enemies, to become stronger.

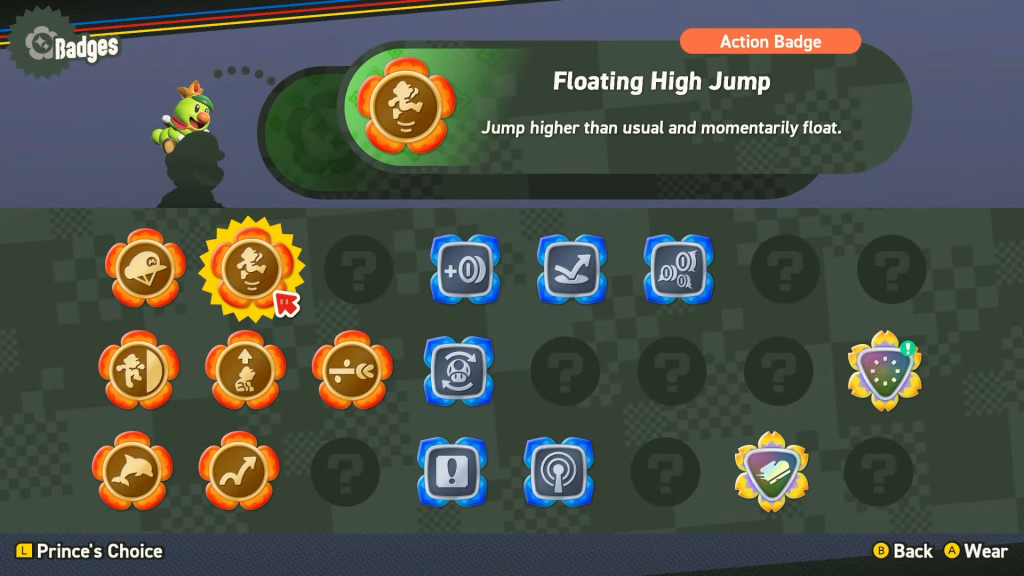

The game goes through each of these, one by one, and strips them down. Decision making is straightforward and boiled down to immediately obvious causes and effects. More on that later. What’s the minimum needed to accomplish skill combination with multiple player characters? Only two, so Paper Mario only has two active player characters at a time. Any more would add complexity. Character loadouts are represented by the badge system – a very simple point-buy system that allows unique abilities to be chosen, but these choices are non-binding and instantly reversible. The RPG convention of experience points is included, but XP totals never exceed 99, and each level up in Paper Mario reduces the traditionally dense cascade of numbers many other RPG level ups have to just one single bonus, chosen by the player from a suite of only three options.

Crucially, however, these simplifications take nothing away from the way their systems interact with one another. Leveling up still incentivizes battling. The limited choices in character progression still affect your strategy going forward. The wrinkle of the action command mechanic – real time inputs that enhance combat abilities – adds a natural point of divergence for different players. Those less skilled in the commands will find battles taking longer, and therefore will benefit more from having a greater health pool, etc. The mechanics which are simplified, still interact with each other in meaningful and impactful ways, experientially.

The badge system was *so* successful, they basically copied the premise for the newest mainline Mario game!

I think it would be helpful to contrast this with a newer Paper Mario game like The Origami King. The boss battles in that game employ a special, proprietary set of game rules (presumably because it was realized that the depthless turn-based combat borrowed from its predecessor Sticker Star could not support an interesting boss fight on their own. cough). The rules are as follows. The boss enemy sits at the center of the play space, which is divided into three rings circling the boss. Each ring in turn is divided into a number of spaces. These spaces can be empty, have a movement arrow facing one of four directions, or have some other action-triggering item. On the player’s turn, they are given a limited amount of time to select the angle at which mario will approach this play space. They can also rotate each of the individual rings to line up the spaces as desired. He enters the outer ring, then travels until he hits a movement arrow, then changes direction. If he hits a contextual or action space, he executes the associated trigger. The goal is to reach the boss enemy at the correct angle to hit their weak spot. However, the boss can also affect the rings, “pushing” them outward, causing each inner ring to become the subsequent outer ring, and creating a new innermost ring.

Now that sounds like a lot of information, and it is, not just intellectually but visually. The game boards for these Origami King boss battles are very noisy to look at. So the set up is like a turn-based RPG, but there are no interesting decisions to be made. The game has a very clear optimal solution which it is funneling you toward. To obfuscate this, Mario’s turn during this boss battles is on a timer, creating an artificial sense of tension, because the decision making of the gameplay has none. There is no substantive way to employ risk for greater reward, nor complex goal to accomplish. The systems at play appear very complex, but the goal is quite simple. The opposite of The Thousand Years Door, in which the player is presented with very simple tools to accomplish a relatively complex goal – defeating enemies with their own suite of tools that you must act and react upon accordingly.

The Thousand Year Door makes something incredibly large from very few, very small parts. Origami King makes something incredibly small from many parts.

Decision Anti-Paralysis

This is a fairly well known phenomenon, so I’ll give the quick version. When presented with too many choices, even if all choices are compelling – perhaps especially so in that case – it actually becomes more difficult to make a choice. What constitutes “too many” choices is highly subject to the individual decision maker and the greater context in which the decision is made, but the phenomenon has an observable effect on how people engage with games. RPGs that drown the player in too many options for play or character customization can easily drive people away, or dissuade them from engaging with the nuances of the RPG systems entirely.

But I think in a strange way, the opposite is also true. If given a selection of options, but a very limited selection of options, each possible choice can feel much more significant, and therefore confer a greater feeling of power and control to you, the player. There is a balance of course. If choices are too limited the player doesn’t feel the freedom of expression inherent to compelling decision making. They feel dragged along, dissatisfied. The three level up choices of Paper Mario represent a good, strong selection of paths to choose for the respective context. Health for durability, staying power, and a safety net. Flower power for those who wish to make liberal use of powerful special abilities. Badge power for those who desire a greater pool of more varied strategic options to choose from.

In The Thousand Year Door Mario, at the outset, only has two attacks – hammer and jump. Even fewer in the first Paper Mario. The two attacks do two very significantly different things. The jump can damage any enemy Mario can touch from above. It can deal two instances of 1 damage. The hammer can damage any enemy on the ground that Mario can reach by walking, and deals a single instance of 2 damage. These very simple rules make every choice feel pivotal. It’s not a question of dealing fire damage vs. ice damage as in the case in many RPGs, it’s a question as to whether your attack will be effective at all, and as the player gains knowledge of how the game works, that knowledge becomes a skill in knowing when and how to deploy their limited choices.

The Value of Low Numbers

Paper Mario prioritizes being intuitive and readable for players of all ages. A lot of RPGs involve a lot of math. Paper Mario isn’t interested in that. Again, we ask the question – what is the bare minimum level of complexity necessary to make an RPG system functional? Do you need to be able to deal 9999 damage? Do we need four digits to account for meaningful measurements of battle power? Super Mario Bros. only had eight worlds, and 64 levels, to make a comparison. That is the number of significant demarcations of difficulty. So maybe an RPG only needs two digits to represent damage? For most of Paper Mario only one digit is needed!

Does the difference between 4882 damage and 5121 damage really matter all that much? Think about it, I mean really think about it. If an enemy has 26000 health, how many times do you have to hit it with one of those four digit numbers to defeat it? The answer is six. Six for both, actually. The ~300 damage between the two is totally irrelevant. White noise. It is actually very unlikely that an enemy has *exactly* enough health to make such a small difference matter. And even then, the difference is only one turn. These number values might as well be 5 damage, and 26 health. Now those stats resemble a Paper Mario enemy, come to think of it.

I could not possibly tell you what on earth is even happening here.

Following a pattern here, although there is a narrower scope to the information density, that can actually be an advantage. Low numbers accomplish two major things. One: the line of causation between player decisions and outcome are clear. When you succeed at an Action Command in Paper Mario, you deal two damage. When you do not, you only deal one damage. In games with higher numbers, the numbers will naturally change more gradually, and constantly, and thus players will not be able to immediately recall what is and is not ‘a lot’ or ‘a little’. This allows players, with minimal investment on their part, to make meaningful decisions that have an immediate, tangible, visible effect.

Of course, it’s not as if smaller numbers are universally better. Larger values offer more granularity, and specificity. There’s more resolution to store information in the integer 1000 than in the integer 10, but practicality isn’t the only consideration here. There’s also just an undeniable appeal to big numbers on their own. Something in our lizard brain loves to see those values biggify. Sometimes reigning in that instinct toward preposterous numeric exaggeration is worth considering, though.

Ahh, yes, every young Mario fan’s favorite leisure time activity: math.

Depth And Intuition

Paper Mario in its original incarnations took a step back and looked at what made up a satisfying progression system in an RPG. What are the barest essentials? Experience points, earned when defeating enemies and stored up by the player, represent progress towards leveling up and getting stronger. In Paper Mario star points take this role. They are likewise earned after battle, but rather than the traditional system in which XP requirements for each level becomes greater and greater to accommodate the leveling curve, a level up in Paper Mario always requires only 100 star points, at acquisition thereof, the player is returned to a count of 0 star points, and works toward earning their next level. This does not negatively impact pacing or the level curve however, as star point yield from defeated enemies scales with the player’s level. The weaker an enemy is in comparison to Mario, the fewer star points he will get. By hiding the mechanism of the leveling curve like this, Paper Mario removes an inherent mental calculus, easing the player’s mental tax, so they can focus on more central aspects of the game. Hiding information like this can be just as impactful as taking it away. RPGs at the time soon started to realize this fact as more and more RPG level progress is being represent as visual indicators like bars that fill up, rather than just overlarge numbers. The immediacy of being able to see one’s progress simply has an undeniable benefit.

And yet, leveling up in Paper Mario is no less satisfying nor compelling for this simplification. This is an example of simplifying without removing core appeal.

Intuition is a key target for those wishing to make games that feel simple to play. Common sense is not common, and appealing to a general or even niche demographic’s natural tendencies is hard. I think it’s one of the most important duties of a designer though: anticipating what your players are thinking. But it is essential that you do – when a game is intuitive, the more naturally play comes. The less you have to explain in detail of your game systems through exposition to the target audience, the better off you are.

Uh… Yeah, kind of the opposite of this.

In Paper Mario, jump attacks are for the air, and hammer attacks are for the ground. However, jump attacks can be used on grounded enemies, many of which react to jumps specifically. Hammer attacks can only hit the nearest grounded enemy. But that also means… Mario can just run underneath flying enemies to reach grounded ones on the backline. Enemies attached to the ceiling aren’t grounded… so a hammer won’t reach them, but there’s no space above, so you can’t jump onto them. However, several of Mario’s partners have projectiles or other attacks that approach from the side. Mario himself can learn a quake move that shakes even the ceiling! All this is obvious to anyone observing, these rules do not assert themselves in big text-heavy tutorials. Combat in Paper Mario is complicated… but it isn’t. It’s all intuitive. Many of its rules speak for themselves. Don’t jump on spiked enemies. Don’t hit exploding enemies with a hammer. Do jump on koopas to flip them over. Use the hammer on more defensive foes. Use the jump to bypass enemies to those on the backline. You can tell just by looking.

The Complexities of Simplicity

Now, a game that is elegant is deep yet simple on the player’s end. It doesn’t mean making such systems work harmoniously is a simple task. An enormous amount of thought was clearly put into Paper Mario. The key is the way in which different systems interact with one another, which takes a great amount of planning. Badge points drive the player’s acquisition of unique abilities, which drives their expenditure of flower points, which drives their ability to get through battles without taking damage, which drives their desire to increase their health points, which drives their desire to obtain star points to level up, which drives their desire to battle enemies, for example. In Paper Mario: Sticker Star, a caustic pattern is established wherein rewards for battle are simply not worth the time and effort (because the combat in that game is boring, you see.) Instantly any inter-system cooperation is cut off, and does not matter to the player. They are no longer compelled to do battle and engage with your combat system, so they simply won’t.

Speaking of making combat engaging and intuitive, I want to comment on the extensive care put into the action commands of Paper Mario. Almost without exception, each of the Action Commands in The Thousand Year door are meant to be abstractions of the actual diagetic action the commanded character is executing. For example, Mario is easy to break down: When Mario uses his basic jump attack, he kicks off of his target with a single, precision strike at just the right moment to get a second jump up successful Action Command. Appropriately, this jump Action Command is a single, precision, well-timed press of the ‘A’ button, or the button already associated with jumping. When using a hammer attack in The Thousand Year Door, the command is a little different. The player must pull the control stick away from the target while Mario is building power, then let it go. This mirrors the motion of applying pressure to pull back a heavy hammer, and then letting its weight carry you into a full overhead swing. Every action command in the game follows a sort of logic like this, but I want to mention one more. One of Mario’s allies is a koopa who attacks by withdrawing into his shell, and spinning up to launch himself at opponents. The action command is to press A, not just as he hits an enemy, but as a constantly scrolling marker overlaps a target point on a bar. Why does it take this form? It represents the spinning! Your PoV is the koopa spinning in his shell, trying to align his target. So clever.

Yes, The Thousand Year Door Is Actually That Good-

-and you should play it when the remake comes out. Seriously though, the purpose of this post is not to convinced anyone of how great The Thousand Year Door Is. I actually approached this from the assumption that the game is indeed effective at fulfilling its design goals, and I wanted to make the case for my observation of how that was accomplished. The genius of the first two Paper Mario games was in how they opened up an extremely storied and nuanced genre for young people. I basically learned to read by playing Paper Mario. It was formative for me, and it practically built the foundation of my understanding of how elegance and intuition in gameplay mechanics worked. I’ve revisited it many, many times and learned a little something about design every time I go back to it. I hope I’ve been able to impart some of that to you.

It HURTS to be this good!