I’ve spent a few hours playing Warner Brothers’ answer to Nintendo’s Super Smash Bros. this week. Yeah, Warner Brothers. Seemingly also an answer to, uh, I guess Viacom’s Nickelodeon All-Star Brawl. (MultiVersus developed by Player First Games and Nickelodeon All-Star Brawl developed by Fair Play Labs and Ludosity). It’s funny video games’ premiere crossover game has met its competition lately from the television and film industry. Or maybe not quite competition. I’ve had a lot of fun playing MultiVersus, and it definitely gives me some of the same chaotic, good vibes of a good Smash Bros. session, but it also feels distinct in some key ways. MultiVersus has been pulling some impressive concurrent player numbers and seems to have drawn a great deal of positive attention. I think there’s a lot of interesting stuff going on here, so these are more or less my first impressions and initial thoughts on the matter.

Drawing People In

I think of lot of MultiVersus‘s initial success can be attributed to some very savvy distribution and marketing decisions on their part. The game dropped with an absolutely delightful fully animated short featuring some of the more surprising inclusions to the game. Fighting games are complicated beasts, and as crucial as their nuances may seem to the enthusiast and designer, it’s often the case that an audience is found by virtue of aesthetics or indeed, character roster. Smash Bros. has earned its reputation as mechanically deep and irrepressibly fun to play, but lots of games are like that – Smash is so huge because it has a singularly unmatched roster of characters. The absurdity of Arya Stark defending Bugs Bunny from a batarang may be matched only by the absurdity of the Iron Giant rolling up alongside actual Superman. MultiVersus starts strong with a trailer that features a great deal of the character roster, including surprising editions with devoted pre-baked fanbases, in out-there abnormal team-ups and head-to-heads.

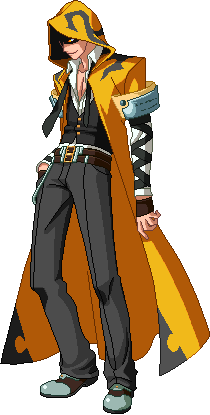

The aesthetic of this game is just appealing too. Not too fancy on graphical fidelity, but the game has a soft, round, inviting look to it and all of its characters. The models are animated well and look quite appealing from the middle-distance a player is going to seem them in the heat of battle. The inclusion of not just voice acting, but the legitimate, genuine article original voices for much of the cast is a huge appeal for me personally. As much passion as Nickelodeon All Star Brawl clearly had, I struggled to maintain an interest in the game when it was eerily silent, without the iconic voices that helped make its cartoon fighting cast stars in the first place. Their post-launched inclusion in an update was much appreciated, but the production values of that game, likely on the basis of budget, simply don’t compare to the push Warner Bros. has clearly given to the development of MultiVersus, financially speaking.

Maybe it’s not that surprising that TV and film companies see opportunity in the crossover fighter space. Original characters, regrettably, just don’t have the kind of draw that legacy characters do for a genre like platform fighter, that has traditionally only maintained a few active games. Even then, Smash is arguably the only one that’s achieved mainstream appeal. When Sony last challenged the throne with PlayStation All-Stars Battle Royale in 2012, they struggled to populate the game’s roster with characters that are as instantly marketable as Superman, Batman, Bugs, Adventure Time‘s Jake The Dog, Tom and Jerry, and, uh, Lebron James. Warner Bros., obviously, owns a lot of properties, so they’ve got an inherent edge in that marketability by way of character roster. Selling on the merits of your character roster is essentially selling on the merits of your game’s possibility for play. When someone sees the Iron Giant – it primes their imagination for what is possible in your game, because even if you don’t know the Iron Giant, he’s a big terrifying metal man with jet boosters. It gets a potential audience excited in a way the presence of something more abstract like a “wave dash” never could. Not that mechanics are unimportant to retaining your audience, but more on that later.

Next to consider, the game is free. Now I have a lot of personal issues with some of the particulars of the game’s monetization strategy, but it cannot be denied that playing the game, at bare minimum, costs not a penny. That’s something MultiVersus has over its contemporaries and seems a natural fit for fighting games. Free-to-play gained a lot of notoriety among business types for its wild success on behalf of games like League of Legends, games about battling between champions chosen from a huge roster of distinct characters sporting unique abilities. A high-skill-ceiling game that rewards intimate knowledge of the game’s intricacies, experimentation with multiple characters, and an understanding of how all the different characters interact. Yeah, a fighting game also seems a good fit.

Finally, with modern netcode and full cross-platform play support, MultiVersus has a refreshingly smooth online experience. For all of its popularity and quality in other areas, Smash Bros. has never been able to say that for itself. I cannot understate how delightful it is to be able to install a game on multiple platforms, pick it up where and when I choose, carrying all of my game progress between machines, and play with any of my friends who are all using their preferred devices. It really makes online games without this feature feel… a little archaic. Honestly, this is the form online gaming always should’ve taken since its inception.

“Platform Fighting Games”

With all that tertiary stuff going for it, it’s no wonder MutiVersus has retained such a player base and media presence in the last few days. People are loving it. A game can’t be carried by media presence alone though and I can confirm that the game is, indeed, fun to play. MultiVersus is a “platform fighting game” like Smash Bros. before it. Smash is certainly the most famous and successful of these, but there have been more platform fighting games than you might think. In addition to the recent Nickelodeon, there’s been a number of indie games following the formula like Brawlhala and Rivals of Aether, and also weird stuff you might’ve never heard of like DreamMix TV World Fighters, developed by Bitstep and published by Hudson, a crossover fighting game featuring the likes of Bomberman and Optimus Prime. Really.

I think one reason platform fighting games haven’t had the same presence as traditional fighters like Street Fighter or Dragon Ball FighterZ, despite one of the genre’s advantages being its beginner-friendly nature, is the ever-present shadow of Super Smash Bros. No other platform fighter has been near as successful as of now, to the point that “platform fighters” were once “smash clones” much as first-person shooters started their history as “doom clones”. But, as with Doom I think there’s been a period of experimentation with with these Smash Bros. off-shoots that have tested the water of what can be done to distinguish oneself from Smash while remaining familiar enough to draw in the players looking for platform fighting games. How much do you change? How much do you keep? Player First Games’ answer? Not too much, but just enough.

Platform fighting games are by nature more beginner friendly than the traditional variety of fighting game, with a greater degree of freedom of movement baked-in, and less reliance on complex minimally-visible mechanics. Multiversus well leans into this strength, even in some ways better than Smash. For example there are much more robust control customization features, allowing you to do things like separating combo moves and charged moves to two different buttons, or swapping what moves are mapped to neutral button presses and directional button presses, among others. Movesets are somewhat limited, even, which could potentially be a mark against it for some, but really does make the game simple to pickup and play. I’d go as far to call it somewhat button-mashy. You may find success just throwing attacks out there. I think there’s some depth to be found here though, the game seems much more naturally suited combo strings that Smash, allowing plays to intuitively juggle their opponents and give chase. And although things can get a little chaotic and hard to read, the action does remain readable if you concentrate, I’ve found, and just a little getting used to if you’re coming from Smash.

There’s a lot familiar here to platform fighter veterans. Characters have their standard attacks, which change depending on directional input, as well as four special attacks likewise influenced by direction. Taking damage makes you more vulnerable to being launched by enemy attacks, and getting launched past the game’s boundaries results in a KO. The ringout KO with ramping knockback from damage is one of Smash’s most elegant inventions, I think. It’s such a natural fit for a fighting game with platforming because it makes one thinking about their standing position within space. Most fighting games exist on an abstract flat plane, with implied impenetrable barriers on either side. The terrain is not a concern there. In platform fighters, where the player’s relationship to the terrain is as important as their relationship to their opponent, a win condition involving the ejection of your opponent from the terrain is brilliant. Some other platform fighters like PlayStation All-Stars Battle Royale have had win conditions that just did not work for me, because they de-emphasized this player relationship to the battle arena in a way that made the platforming capabilities of the characters feel somewhat redundant. MultiVersus knows what to crib from its contemporaries.

It’s also a little different though. Weird and unique decisions like giving Finn the Human from Adventure Time the ability to charge his attacks while moving keep the game fresh. Most characters have such small interesting unique mechanics, in addition to bigger and noticeable ones. On a broader scale, this game has some intense aerial mobility. Every character practically plays like Sora from Super Smash Bros. Ultimate, flowing nimbly through the air at high speeds. In Smash, players are allowed two jumps and a recovery attack to stop themselves from falling off the arena. In MutliVersus, you can use a recovery twice, air-dodge twice, then climb up an vertical surface. They really didn’t want people falling off the stage by accident. In free-for-all mode, the edges of the play area draw in, making the safe ground smaller when the round’s timer nears its end. It’s a pretty elegant way to prevent camping, an often reviled somewhat bad-faith way of playing, which I think is quite clever, especially in a ‘just for fun’ party mode like free-for-all. I always appreciate fighting games that encourage engaging the enemy and utilizing the fighting mechanics, rather than just turtling up or running away.

Another unique and rather clever angle the game has is that it’s 2v2 focused. Now this is a mechanic that I think does come across somewhat in building your initial audience, because it has such an overriding effect on the game’s design and, like the character roster, is something that can spark a general audience’s imagination. Some people play games for the experience of being a support role for their friends. These people, I’d say, are less likely to play traditional fighting games, but the presence of characters with a support-specific focus like Wonder Woman or Reindog might be appealing to them. You can really feel the way the game wants to encourage team-play too. The presence of cooldowns, a rarity in Smash Bros., encourages teams coordinating their available resources and the timing of their most valuable moves. Having support roles in a fighting games allows MultiVersus to do things that Smash simply doesn’t, carving its own niche.

The game also just makes some design decisions for their fighters that just seems very… not Smash, not necessarily in a bad way. Smash is far from creatively stifled but it does have a little bit of a brand, and that’s fine. It’s nice to see its contemporaries establish their own brand though! Some of the wacky stuff characters can do feel like things Smash didn’t really start doing until the later downloadable characters of Super Smash Bros. Ultimate. When I see the Iron Giant enormously stomping around the battlefield in MultiVersus I can’t help but think of the years hand-wringing online discourse had about the inclusion of “too big” space dragon Ridley from the Metroid series as a fighter in Smash. He got in anyway (and I will go to my grave being smug about that), but at quite a modest relative size. I love the depiction of Ridley in Smash, he’s practically perfect. Iron Giant though, I think is going to be a very memorable fighter in his own right, because the developers of MultiVersus feel so unrestrained by tradition, while respecting the foundations that were the inception of the genre they’re iterating on.

There’s a lot more to see and learn about MultiVersus. I’m sure there’s an encyclopedia’s worth of knowledge yet to be discovered about combo strings, frame data, tier lists, and other such silliness, but on first blush the game is a blast and is doing a commendable job of setting itself apart from obvious comparisons. It’s production values are exceptional, its roster is absolutely wild and it’s free… more or less. My issues with monetization are the biggest sticking point for me. I don’t know if I want to talk about that here, though. At any rate, I’ve had platform fighters on the brain and wanted to get my thoughts out there.

Mathematical!