If you’ve ever been in a literature class you may know the basics of how characterization is generally conveyed – how a character acts, how a character speaks, how other characters act and speak in response. Typically this is done through audio and visuals, you can see and hear all these things play out to get an idea of a character’s personality and vibe. Games, of course, have their own interactive advantage. There’s a way to characterized that only games are capable of. The way a character plays, the way the systems and mechanics that make up their utility incentivize and reward certain methods of play can also be tools of characterization. There’s personality in a playstyle.

I’ll be using as a case study Yuuki Terumi from the traditional 2D fighting game Blazblue, as I think this character is a particularly acute example of what I’m talking about. A fighting game, specifically a traditional 2D one, if you didn’t know, is a game about pitting two fighters, each controlled by a player or an AI, against each other in a relatively small arena, with nothing but their fists (or swords) and their wits. First guy to die loses. A game more or less similar to Blazblue you may have heard of is Street Fighter. Fighting games can get pretty heady with strategies and counter-strategies, feints, double-fake-outs, predictions, counter-predictions, etc. There are a lot of moving parts and a lot of interesting player behaviors that go into a fighting game match, so there’s also a lot of room to explore game mechanics to characterize these behaviors.

I’ll try to give the simplest explanation for the rules of fighting games to define our terms here. Each player (or AI) picks a fighter from a roster of unique combatants. They try to hit each other without being hit in return. Landing a hit generates meter, a special resource that can be spent on special, powerful maneuvers. Getting hit also generates meter, but slightly less, while you lose HP. When your HP reaches zero, you’re out.

Games are defined by their rules, and so it is with playable characters. Even in the most open-ended game one cannot do anything in the play space. You’ll always be limited by what your play avatar or player character is or isn’t capable of. Given this inherent fact, the design of what can or can’t be done in a game defines the game’s character. When you’re assuming the role of Pac-Man, you play a hungry guy who loves fruit, is wary of ghosts, but is also quick to turn the tables on those ghosts when he gets the upper hand. Well, that’s all that Pac-Man is capable of, which is exactly the point. It’s extremely rudimentary in the case of Pac-Man, but this basic idea of characterizing through play can be expanded far in a lot of directions. When a player is incentivized to behave a certain way in a given play space, it characterizes their play, which can reflect on the character they are playing.

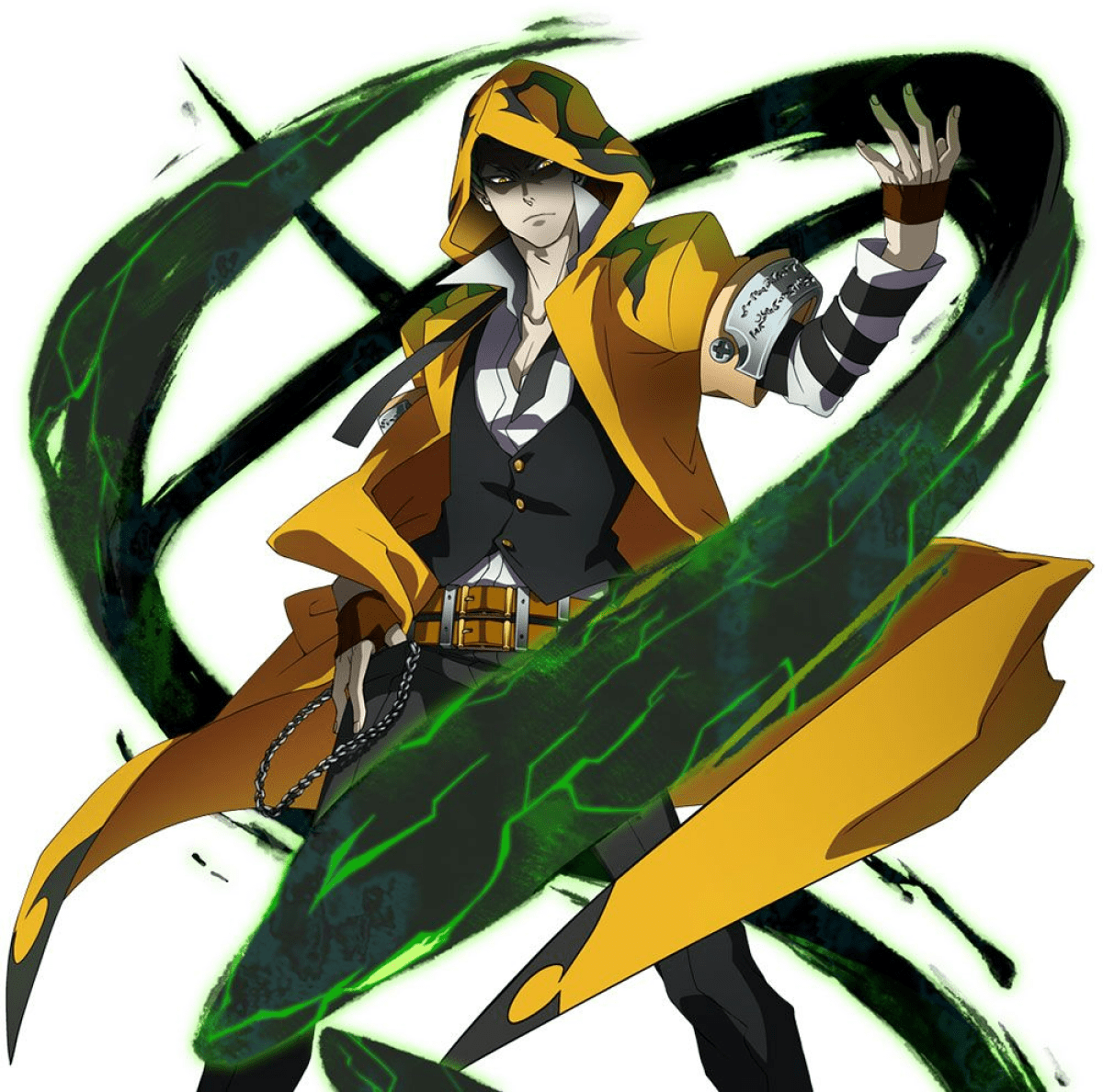

So how does Blazblue accomplish this in this case of Yuuki Terumi? Characterization begins with first impressions, and the first you’ll get of Terumi is his appearance, so let’s have a look.

Good God. He looks like a used car salesman half-heartedly dressed in a voldemort costume cobbled together at the last minute from miscellaneous articles found in a party city. He is impossibly cool. I will never achieve a fraction of this man’s sense of style. LOVE this guy. So there’s not a lot to go on here without further context within Blazblue‘s world. Some people might have that context, but many won’t, picking up the game mostly interested in some fun fighting game versus action without delving into the story mode. We get the sense from his posture that Terumi is perhaps a shady, underhanded fellow. He wears a suit, but loosely, maybe it’s just a facade of professionalism. The bright yellow cloak with wicked black patterns on it is a lot more striking and threatening, maybe even villainous.

Terumi is what’s known in fighting game communities as a rushdown character, meaning to succeed he generally wants to get in an opponent’s face, put up an oppressive offense, and not let up. Let’s take a look at some of Terumi’s basic moves to see how they reinforce this playstyle.

Basically everything Terumi can do, is either fairly short-ranged, or physically moves his character forward, toward the opponent. The game is trying to gently nudge all Terumi players to behave in a certain way – close in on your foe quickly, and use the tight space to your advantage. “Attack, attack, ATTACK!”, the game seems to say. Playing rushdown is all about keeping your foe guessing to get around any potential defenses they may mount against you. In a word, you’re manipulating your opponent into making mistakes, never giving them a moment to breathe. You want to make them seem stupid. You want to be dancing circles around them. Aggression and manipulation. It’s a pretty elegant abstraction of Terumi’s proclivity for psychological torment. It all paints a pretty vivid picture of a man that thrives off of schadenfreude, who feels superior, who’s powerful and knows it. I mean how often do you see curb stomping as a gameplay mechanic? Absolutely brutal.

One of Blazblue‘s primary mechanics is drive. It’s a special form of magic attack unique to each fighter, providing a unique mechanic that individualizes each character’s play style. Differentiation like this is great for making each fighter feel different, which is further great for your game’s variety and long term interest. It’s also excellent for characterization, with each drive mechanic reflecting on the characters’ various personalities. In Terumi’s case, his drive is called Force Eater, and its unique mechanic is as follows. Normally, as I mentioned earlier, each of the two fighters on screen build up meter when they deal or receive damage – more meter in the case of the dealer than the receiver. However, when Terumi deals damage with his Force Eater, he steals all of the meter his opponent would have generated through received damage, for himself.

It’s pretty intuitive that taking anything from a player that feels rightfully theirs makes things personal, and that’s the idea. Terumi breaks the almost sacrosanct understanding that taking damage refunds a resource as a consolation, but nothing is sacred to Terumi. It’s a subtle thing. Your opponent may not even notice that you’re stealing from them, but as a Terumi player you’ll know. You feel like an absolute bastard for doing this and it’s great. This is your primary method of generating meter, and how you fuel your play as Terumi. To be Yuuki Terumi means taking from others to survive. If you follow the game world’s narrative definitions that meter = magic = the soul, then Terumi eats away at his opponents’ souls to fight them. Pretty apt. The end result of all this is that Yuuki Terumi can generate a dizzying amount of meter in a very short amount of time, which further reinforces the next point I want to discuss, his supers.

In traditional fighting games like Blazblue, a super is a big, stylish, spectacle-rich attack that deals a lot of damage at the cost of some of your meter. It’s the big haymaker attack that you gradually build up to. Most characters in Blazblue have two normal supers to choose from, sometimes three, and rarely even four. Terumi has SIX. In fact, most of his versatility as a fighter comes from his supers. Tools that some more specialized characters might have, like counters and and ranged attacks, are only available to Terumi through his supers, requiring him to spend meter to use them. So not only is Terumi a power-hungry soul eater, but he also delights in spending enormous amounts of that magical energy he siphons, burning through it like it’s nothing, unleashing a deluge of power other characters struggle to scratch the surface of. Because Terumi can generate so much meter so easily, you as a Terumi player are almost always flooded with the stuff. You cap out at 100 meter, and money in the bank does nothing for you, so it’s most efficient to be spending it frequently. This promotes an extremely aggressive playstyle, which is good, because Terumi is an aggressive guy.

You’ll notice a lot of growling, sneering, and jeering coming from Terumi. He’s constantly berating, insulting, and taunting his opponents. He clearly doesn’t think much of them and wants them to know it. Gameplay is the core of what we’re talking about here, but gameplay has to work in concert with audio and visuals – all three are essential to the overall experience. The animation does a lot of heavy lifting here too, as you may have noticed. It can communicate some nuances of Terumi’s character that don’t quite come out through gameplay alone, such as the elegant yet slippery, almost dance-like way he moves, like a snake. There’s also a lot of snake imagery here. Okay yes, the snake thing isn’t all that subtle. Terumi = snake.

Feeling superior isn’t just a kick for this guy, it’s like an obsession, or a need. It’s as if he’d disappear in a puff of green smoke if ever a single person in a room with him wasn’t made to feel lower than a worm. He’s powerful, and he knows it. From his unassuming form he can unleash a torrent of magic that puts others to shame, and he loves doing it. He’s cruel, sadistic, and aggressive. He doesn’t want to just stomp you into the dirt, he wants to machine-gun stomp you a thousand times per minute until you’re a red paste on the ground. The game treats you like a bloodthirsty sadist, so that’s what you become to play Terumi. Blazblue is so effective at this, I often find myself repeating caught up in Terumi’s rapturous celebration of his own ability when I land a particularly nasty combo. It’s all in good fun, of course. Of course. Is this that “role playing” I’ve heard so much about? They should make games about that kind of thing.

So how do you make your player feel like Spiderman.. or Batman, or Pac-Man or whoever? Build systems that incentivize behaviors reflective of Spiderman. Construct your gameplay mechanics around these behaviors so that a player will naturally be inclined toward doing things that Spiderman would do, and back up these behaviors with coordinated audio and visuals that promote feeling the way that Spiderman would feel. If your gameplay mechanics are built well, if they’re fun, you can even give players a reason to have fun roleplaying. Becoming a character within a narrative is something you can only do with a game, so make it fun to become your game characters for a time and make an experience players can’t have anywhere else.

Stand up! I’m not satisfied yet…