Boss breakdown again! It’s been a while. What’s a boss breakdown? It’s a design exercise. I try to break down, to the fundamental particles, what makes up a boss fight, how its design operates under the hood, and analyze the result. Design goals, what the design accomplished, the whys, the hows, and everything between.

For this boss breakdown I want to do something a little different. I’m going to compare two versions of the same boss fight. The boss I’m going to break down is Dark Mantis from Mega Man X8 for the Playstation 2. Interestingly, one of the versions is a fan-made recreation, meant to be evocative of the 16-bit classic Mega Man X games. This ‘demake’ in question is being developed by one AlyssonDaPaz. I played a lot of this game when I was a kid, and I have fond memories of it. On balance I’d say it’s a pretty good game, but it is far from the best of the Mega Man or even the X series. It was the first game in the series following the less-than-fondly-remembered Mega Man X6 and Mega Man X7, which are both… extraordinarily flawed, each in their own way. Maybe I’ll talk about those one day. My point is that X8 was a case of the franchise trying to re-find its footing after a rough patch, and as only the 2nd ever 3D game of the main series Mega Man games, it was still experimenting on how best to leverage these new capabilities with a classic formula. The ‘demake’ Dark Mantis has no such baggage nor extant goals. The fascinating thing about fan remakes and demakes like these, I think, is how they are inherently made with the benefit of hindsight, and the added context of being made by someone a fan – a distinct perspective that colors how the design is approached.

Dark Mantis, narratively, is an assassin-type robot modeled after a praying mantis with blades attached to his arms. He skulks about in the dark for a quick, clean kill. So, a lot of his design is going to reflect that. He has a lot of fast, sudden movements to reflect this. In the original, he has two basic behaviors – hopping back and forth a short distance on the ground, from which he will react with an attack based on player-proximity, and his second behavior; jumping back and forth across the top of the screen, from wall to wall. In the demake, his hopping behavior, which characterized Dark Mantis as very cautious and careful, looking for the opportune moment to strike, has been removed. In the practice the hopping behavior slowed the pace of the fight, leaving the player more room to breathe. This reflects the design philosophy of most of the bosses of Mega Man X8, none of which are extraordinarily fast pace. In the demake, Dark Mantis is basically always attacking, with very little downtime between each attack routine. This characterizes him more as a merciless, vicious killer that dispatches his opponents quickly and efficiently. If you want my opinion, the demake does, with the benefit of hindsight, characterized the mantis better through his design – more accurately matching his written dialogue and descriptions as presented.

He still bounces between the top corners of the screen by clinging to walls, but this has been altered in the demake. In the original, this behavior would keep the player away of their relative position on the ground and discourage abusing the walls to avoid attacks too easily, and Dark Mantis would otherwise have trouble hitting players hiding in those top corners. Forcing the player to the ground also encourages them into close proximity – appropriate for this more melee-oriented boss fight. The demake version fills this some purpose, but also includes the fan version’s first new attack not present in the original. Dark Mantis will, after one or several hops, drop straight vertically out of the air, bearing his blades down when he is exactly above the player. So the player must not only be aware of their relative position on the ground, but the number of hops Dark Mantis has done, and otherwise be prepared to react with a dash to dodge out of the way. This adds a sense of tension to the behavior that the original did not have. While in the original you did not know when Dark Mantis would drop from the wall, you could always preemptively move to the opposite wall. There is no such option with his plunging attack, so the player must always be prepared to react.

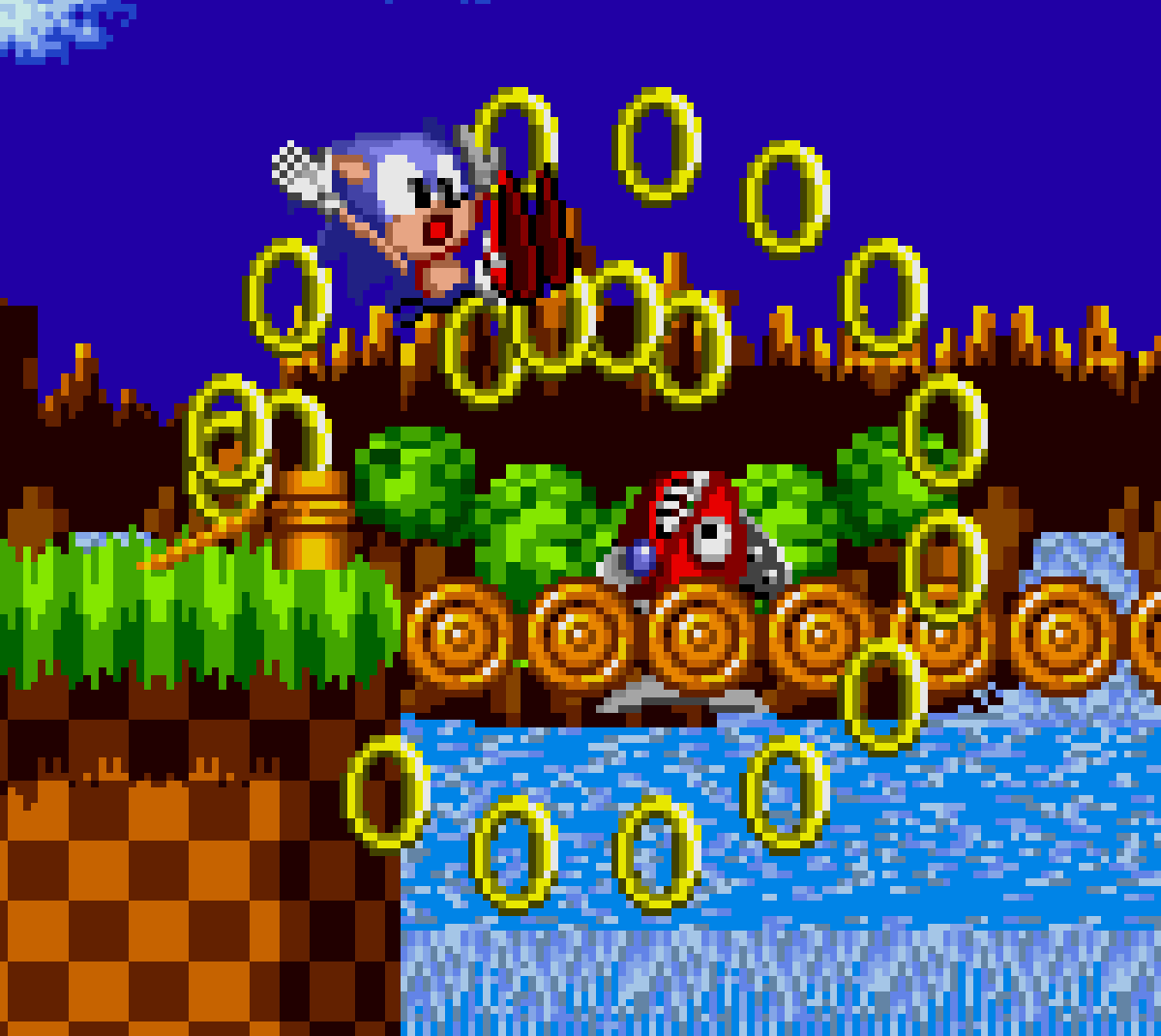

Left: Plunging Attack, Right: Shadow runner

Shadow runner is an attack that is in the original and not the remake. Which is ironic, seeing as how in the original, Shadow Runner is one of the attacks the titular X can copy from Dark Mantis after he is defeated. What it does, is produce a shadowy arrow projectile that travels horizontally, then spins outward when it reaches a close proximity to the player. This gave Dark Mantis an extra ranged option, to cover for his more melee-focus. It’s easily dodged though, by jumping over or dashing under it. It’s removal from the demake makes sense, as Dark Mantis is given an even more keen melee focus, and he much more aggressively forces the player into close proximity with him, making Shadow Runner kind of redundant.

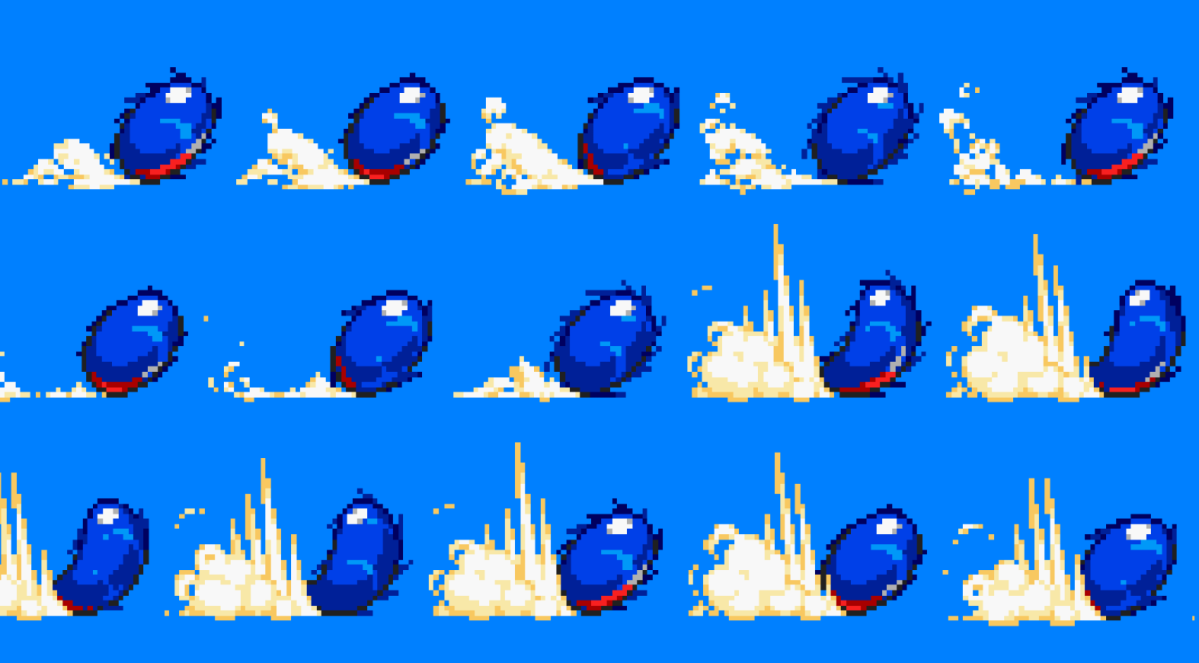

Aside: The animation and sprite work on this fan game is just gorgeous.

Next, we have Blood Scythe, which works a bit differently between versions. The original has Dark Mantis travel a set distance forward in a fast dash when the player is close enough in front of him. He may hop into this range, or the player may enter it to trigger. To dodge the player simply has to dash or jump out of the way fast enough, or else be restrained by Dark Mantis. While restrained, the player will take a small amount of damage, but Dark Mantis will have his hp restored slowly in turn, making this a highly punishing attack. This serves the purpose of making the player always away of Dark Mantis’s proximity to them. He is meant to be deadly up-close with those plays, so this attack reinforces that idea. In the original the attack can be ended early by using the assist mechanic, in which one of the player’s two controlled heroes assists the other to escape, and takes his place in the action. The demake understandably removed this mechanic, and multiple playable characters in general, presumably for simplicity and scope reasons. There is another notable difference to the demake’s blood scythe and that is its movement. Its lateral movement is now slower, but will travel however far is necessary to reach the player, before initiating the grab.

Ah yes, praying mantises, well known for… sucking blood? Robot blood?

This ties into another new attack added in the demake. When Dark Mantis is on the ground and detects the player is also on the ground, he may choose to initiate one of two attacks and move him across the entire arena from his current position until he reaches the player or a wall. In the first is bloodscythe, the second is close-ranged a slashing attack. Relatively, bloodscythe has a lot more startup time and moves slightly slower than the slash. He assumes two very different poses depending on which he will initiate – raising both blade arms for bloodscythe, and moving one blade to his hip in a low stance for the slashing attack. In many cases in Mega Man X game it is the player’s instinct to dash and jump to dodge attacks – as most attacks do not cover a wide area, this offers the most vectors of escape; up and away. It takes a good amount of discipline and conscientiousness to resist this impulse, which is what the slashing attack demands. Dark Mantis propels himself with the slash just high enough into the air that it can be dodged if the player is in a dash state, in which their hitbox is shorter. If they also jump, obviously they will be struck. Dashing and jumping is the optimal strategy to avoid bloodscythe, but not the slash. This new dynamic introduced to the fight ensures the player has to keep their eyes on Dark Mantis and watch for his tells.

This animation on this attack is really well done – dynamic and threatening.

This forms a new core identity to the demake version of Dark Mantis. The slashing attack and bloodscythe become two of his most common attacks, and thus represent an ever present threat that demands skills of reflex, observation, and control. The slashing move is then followed by a short-ranged projectile that can be dodged easily enough, but adds to the complexity of the move as something you still need to be aware of.

Finally there’s the attack black arrow. It’s a spray of projectiles that launch up, and in an arc, spreading out as they go, then coming down on the position the player was in when they were launched. To dodge, anticipate where the arrows will fall, and stand in the safe gaps between them. The in demake, this further serves as a sort of misdirection. Because Dark Mantis has so little down time between attacks, his black arrow becomes a kind of provurbial smoke screen to draw player attention away while he prepares his next move. Black arrow is very similar between the versions, but demake Dark Mantis’s black arrow attack is a lot easier to see, in general. That makes it easier to dodge, but also less frustrating to deal with in general.

Something black arrow draws into focus is the fight’s readability. Readability is essential for fast-paced action games like Mega Man. If the game is all about spatial relationships, reaction, and timing, the player’s got to see what they’re reacting to and time, and where it’s coming from, right? Now, the intentional obscuring of information like where a projectile is at any given time can be leveraged for an extra change of pace and challenge, which I presume is what the original X8 was intending, but this can very easily become frustrating. You see, each level in Mega Man X8 has some sort of unique level mechanic or gimmick, to distinctify the stage. This could have been done for any number of reasons. It’s possible it was just to give the game its own signature style compared to other Mega Man games, or it could’ve been done to broaden the game’s appeal to a more general audience, or for any other reason. In Dark Mantis’s stage, the gimmick is a generator that, when activated, turns on all the lights in the dark, shadowy level. This includes a light in Mantis’s own boss room. In light, he’s much easier to see.

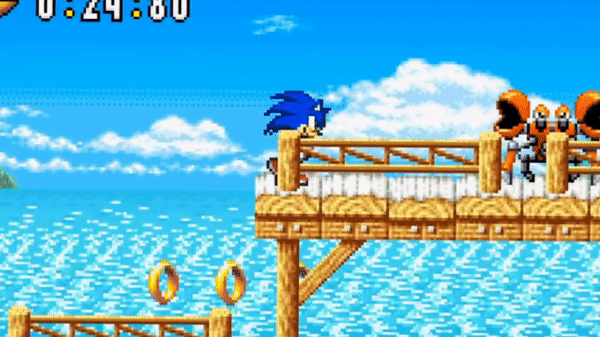

Side by side like this, its easy to see which version is *much* more readable.

Even with the light though, demake Dark Mantis is just a lot easier to see. This is a side effect of him being a 2D sprite. 2D sprites are a lot easier to make readable than 3D. The artistic techniques necessary to make 2D art readable are less system-dependent as well. 2D sprites can have definite outlines without need of external program scripts, for instance. For a further example of what I mean, consider that 2D Dark Mantis is not lit by any particular source of light in the room. He has shading, but it is general purpose – meant to look good from any position in the room in which he appears. His body catches light as illustrated, but not from any particular angle. With this in mind, 2D sprites do not have to have the same relationship of color and light to their background as 3D models do to look natural. Demake Dark Mantis is actually a lot brighter on the screen than his shadowy background may imply – he actually consists of mostly mid-tones – but it doesn’t look jarring. That contrast does make him highly readable at a glance, though.

Original Dark Mantis, on the other hand, has to “blend” more with his environment, or his 3D model would stick out in a jarring way that would seem amateurish. A 3D model’s poses also have to be manually puppeteered, and a 3D model’s anatomy cannot easily be exaggerated the way a 2D sprite’s can to convey the artist’s intended look and feel. 2D drawings can be contorted in ways 3D models can’t to be more readable.

At this point the difference in direction here is definitely starting to come into focus for me. One of the main things, I think, is difficulty. Mega Man x8, particularly in comparison to other Mega Man games, is not extremely difficult. It’s no pushover, on the harder difficulty settings, but the most critically beloved Mega Man games can be some real killers. The series kind of has a reputation for it, actually, and that sense of intense challenge is a big appeal for a lot of its core audience.

I’m about to engage in some protracted speculation here.

Something to understand about Mega Man as a franchise: It’s never been a blockbuster seller. Mega Man the character is one of the most famous video game icons, period. Everybody knows Mega Man. The people love him. Thing is, that popularity never especially translated to sales. However, it’s a series with about 50 or so entries, even if you’re counting conservatively. My point is, these are highly technical games with a huge skill ceiling, and an often unyielding skill floor. Some niche, fairly hardcore games, for a niche hardcore audience. They inherently don’t have the same mass market appeal as a Mario, or even a Sonic. This was never a problem for a long time, because these games typically did not cost a great deal to make. Each sequel made extensive use of art assets recycled from the one previous, was made in a fairly short amount of time, and introduced only moderate iteration along the way.

Mega Man games were fast turnaround, low risk, with a loyal and devoted audience of hardcores. That is, until 2D games started to temporarily lose popularity in the advent of 3D graphics. It didn’t seem temporary at the time, though. Here’s the speculation: 3D games are comparatively very expensive to make. If Mega Man were to survive, it’d need to establish a broader market appeal. And so, the two 3D games in the main Mega Man series of platformers, are also known for being quite a bit less refined in terms of skill investment, and a bit less difficult than the other games. All this to say, I speculate a reprioritization to make these games more generally appealing coincides with their transition to 3D, to make up for the cost of production.

That tangent out of the way, the demake version of Dark Mantis holds no such priorities. This version of the insectoid assassin was clearly made to be more evocative of the very difficult bosses of older Mega Man games, with their zippy movements, narrow dodge windows, and rapid fire attacks. And when I say ‘difficult’ I mean specifically designed to better reward full understanding and leverage of the player’s movement capabilities. This is what the demake version of Dark Mantis has two dash attacks, and a much faster desperation attack. These are meant to further push the player’s understanding of how much distance they can clear quickly, and in what directions that distance can be covered, along with a bit of reaction time testing.

Finally, both versions of the boss share a mechanic whose archetype appears in several games. I tend to call this a ‘desperation attack’, although I believe the official Mega Man is ‘overdrive attack’. It’s a special, rare, extremely powerful and high-spectacle move that fully shows off the boss character’s power, and in theory fully puts the player’s skills and knowledge to the test, as one final high-tension show stopper. This is a new addition with Mega Man X8 and I have to say it’s a brilliant one. These sorts of things offer a lot of opportunity to characterize boss enemies, from their dialogue to their design, and make a fight a lot more memorable, by giving it a real signature and identity. I do have to say though, Dark Mantis has one of the easier overdrive attacks in the original game to deal with. He jumps to, and floats at the top of the screen and arena, then winds up a glowing scythe over one shoulder. A second later, he slashes one half of the arena entirely, dealing massive damage – always the side opposite the windup. He then repeats the attack on the opposite side. This is a really cool attack, conceptually, and from sheer spectacle I really think it does its job of characterizing Dark Mantis and making him very memorable.

“I wanna see you CRY!”

The demake version once again ups the ante in terms of difficulty and challenge. The attack is basically the same, except the slash is now *even larger*, encompassing more than half of the arena, requiring a well-timed dash jump at a specific angle, and memorization of the attack pattern. That, and he will alternate slashing the left and right halves of the screen several times before his attack is done. This all makes the move much more menacing, and Dark Mantis as a result a lot more impressive, so I have to praise that. I would say it is perhaps a little less reasonable to be able to dodge this move the first go around, compared to the original, and while the enormity of the slashing effect reads perfectly well after the fact, it’s a little tough to predict that will happen if you haven’t seen it before. This is a little harder to work around, as part of the point of this assassination attack is that it has only a very subtle warning compared to its monstrous effect.

As a longtime and very hardcore action platformer(and Mega Man in particular) fan myself, I have to admit my bias for the more challenging, fast-paced Dark Mantis of the demake. I do have to reiterate that remakes and remasters, especially fan-made ones, have very different circumstances and context to the original design. I in no way mean to disparage the very talented folks behind Mega Man X8, they did not have the hindsight and their own game and future games to draw on. I do have to praise AlyssonDaPaz for his impressive work in re-adapting this boss fight for the kind of fan it’s clearly intended for – that is, longtime hardcore Mega Man fans. I think X8 was likely aiming for a broader audience and many of its design decisions reflect that. I hope you found this interesting. I know I always find boss analysis fascinating, and this sort of comparison is a rare and very educational opportunity. I feel like I was able to learn a lot from this.

Your actions are those of a Maverick!