I’ve been playing a lot of Final Fantasy XIV! Yes, I’m one of those! Blame my friends, they got to me at last. I had an interesting thought, the other day. If you haven’t played Final Fantasy XIV, hereafter frequently referred to as FFXIV, then you might not understand that its combat feels very different from the likes of more “standard” MMOs of the years’ past like World of Warcraft. There’s a number of certain somethings in the nuances of its design that piqued my interest, made me question what makes them tick. What’s more, the more I thought about these little nuances the more I found surprising parallels in other games that you might not expect. So, if only to satisfy my own curiosity, I’d like to try and break down what about FFXIV’s combat sets it apart, in my estimation, and what can be learned from how XIV does things.

Now, if I describe aspects of Final Fantasy XIV that come from different expansions that were released years apart, please do not be dissuaded. The entire development history of the game is characterized by slow and highly iterative adaptation to its changing goals and aspirations. Even the game’s own narrative reflects this, but all that’s a story for another day. Suffice to say, even though FFXIV took about a decade to come out, in a drip feed, it is presently very much a complete and cohesive product worth investigating on the whole of its merits, in addition to the individual merits of its expansions.

The Core Mechanics

First, to understand how Final Fantasy XIV becomes ‘playful’, as the title up there indicates, we need to understand, like all newbie players, the baseline that the game expects of you during combat. To start, each player has a combat job, who fills some sort of role. The primary roles are tank, who absorbs most of the damage and the enemies’ ire, the healers, who provide healing support, and the damage dealers, whose specialty is obvious, and are further divided into ranged, melee, and magic damage dealers. Each of these jobs need to maximize their effectiveness to get through the most difficult encounters. Managing their resources correctly, pressing the right buttons and casting the right spells in the right order, is all essential.

There is an optimal way to do this. There is not room for much personal expression through play in the combat of Final Fantasy XIV. I think that’s fine, as this MMO concentrates much of its avenues of personal expression elsewhere. The playfulness of its combat lies elsewhere than in the individual players, as well. But back to the subject, if a player is experienced, their performance will more and more approach this optimal sequence of player actions, that deal the maximum damage, absorb damage most efficiently, or heal most efficiently. This is their ‘rotation’. Players are expected to constantly be tending their rotations in combat for maximum efficiency.

However, the enemies in this game have special attacks that can hit multiple players, and not just the tanks. These are called Area of Effect attacks, or AoEs. These are (almost) always indicated by bright orange volumes on the flat 2D surface of the ground. Some players might humorously say “there are lines on the floor” when ribbing each other’s performance. And indeed, to dodge an AoE, one must step out of the bright orange shape, before it resolves. The orange AoEs are a rather ingenious way of injecting some more engaging movement to the otherwise rather static tradition of “tanking and spanking” enemies as was often said in World of Warcraft. The AoE markers are calculated server-side, meaning their mechanics must be communicated to the greater online sphere before they resolve on an individual player’s client, as AoEs are by definition meant to affect multiple players. If an enemy were to just swing his arm without such a warning in real-time, the differential between client and server could make for a rather inaccurately timed and unpleasant experience. So instead, the developers opted to essentially slow down the process of dodging attacks a lot.

These bright orange “danger” volumes become go-to shorthand in combat.

This, obviously, makes FFXIV a whole lot easier than, say, a real-time game like monster hunter (at least at first, but we’ll get there), and itself not quite an action game. The developers were aware of this too, of course, so instead of relying on players’ reactive abilities, they test players’ predictive abilities. AoE attacks come out slowly. Usually. And they have very clear indicated boundaries. They always resolve a static amount of time after appearing. So what happens if there’s a large AoE, leaving only a small safe zone… but then, another AoE appears, a couple seconds later but before the first resolves, and covers that safe zone? Now you are tracking two timers, splitting your attention.

Remember this is all happening while players continue to triage their rotations. FFXIV is a game that demands multitasking as a core skill. You might have heard this, but the human brain is actually exceptionally bad at engaging in several activities at once. When you ‘multitask’, what you’re really doing is rapidly shifting attention from one activity to the next, and back, ensuring no one activity becomes too neglected, like spinning plates. In the example I provided, you must manage your rotation, but also be aware of the first AoE’s timer, and not be distracted by the fact that a second AoE is overlapping your safe zone. Because as soon as that timer goes off, you must concern yourself with the second, delayed AoE’s timer, and vacate from the initial safe zone. Oh, and don’t forget to keep up with that rotation. Don’t want to fall behind on damage.

So from what at first seems like a rather basic combat design basis, we get some versatility with basically… messing with player cognition to a great degree. Imagine barrages of AoEs, all different sizes and shapes, all slightly offset from each other in space and time. Maybe some AoEs that respond to player movement, and some that depend on player facing direction. Pretty quickly the demands of multitasking become quite frantic. I don’t have to imagine it, I’ve lived it. It doesn’t end there, though. With these basic rules in place, Final Fantasy XIV, instead of only intensifying the existing mechanics, constantly introduces entirely new ones, with their own demands of the player’s time and attention. So how can they keep the constant barrage of new information from overwhelming the player? If the rules are constantly changing, how does the encounter design stay intuitive?

“Intuitive”

To figure that out, we need to decide what’s “intuitive.” using or based on what one feels to be true even without conscious reasoning; instinctive. Thanks Oxford, but, hm. Okay, that doesn’t help us much. How do we know what our players will feel to be true “even without conscious reasoning”? Let’s hone in on that last word – instinctive. We can start by using signifiers that relate to general knowledge the average player in our demographic would bring with them into the game. This often translates to relying on real world “common knowledge” as a basis for gameplay mechanics. If there are two towers, one taller than the other, and lightning is about to strike, which tower should you stand under?

As you can see, in the chaos, following simple instructions can be challenging.

FFXIV is, once you’ve acclimated to the basis of its combat system, rather consistently good at this. Most of the time, it is possible, perhaps even feasible, to discern most of what an enemy might be capable of based on this sort of “common knowledge” intuition. When an enemy raises their right hand, it is likely unwise to stand on their right flank. A dragon will probably breathe fire in a cone in front of itself. If a boss is charging a massive attack, with tons of energized particle effects to accentuate, and a rock that is roughly the size of play character falls onto the ground, then it is probably advisable to put the rock between yourself and the enemy boss.

That last one is intuitive on a “common knowledge” basis, but it also overlaps with another kind of gameplay intuition, which is pattern recognition. Generally, human brains are very very good at recognizing patterns. When FFXIV introduces a new mechanic, it can be considered to be establishing a paradigm. As that mechanic may appear again, sometimes very frequently! In addition to the “core” mechanics of FFXIV combat discussed earlier, the game deploys additional mechanics with a particular kind of consistency of logic. For example, eventually a player working their way through the main story of FFXIV will find themselves fighting an ancient dragon. This dragon will use an ability called ‘Akh Morn.’ Prior to its activation, this ability is foreshadowed by the standard ‘stack’ mechanic indicator, meaning players must huddle together to split the damage. Akh Morn, however, hits multiple times – so if players scatter after the first hit as they’re used to, they must react to reconvene, if they’re to survive. Later, they will fight a dragon again, and Akh Morn will once again occur, and work the very same way. At this point, it will become clear that Akh Morn is an ability specifically associated with dragons, and players will be prepared for it any time they see one, even before the ability is used. This is also a kind of intuition, based upon a sense for the shape of the gameplay’s design and intentions, in recognition of established patterns. One might even call it gamesense.

FFXIV overlapping its mechanics makes players more predictive than reactive.

That’s all well and good, but this is all kind of fuzzy, isn’t it? Indefinite terms like “common knowledge”, and even pattern recognition will not be consistent across all players – each individual learns at a different pace. So how can you tell what is intuitive? There’s no real definite approach outside of using best judgment, and then playtesting. Playtesting playtesting playtesting. You’ll never really know how players will react to certain gameplay decisions until you see players react to those gameplay decisions. Seeing your players engage with your systems will inform your approach. This can be seen in how enemies and combat mechanics in FFXIV change gradually, but significantly over the course of its story quest – through many iterations across several expansions that came out over the course of a decade.

Final Fantasy XIV and Undertale Are The Same Game

I am especially fond of how FFXIV uses that “common knowledge intuition” to introduce its new combat mechanics. I have a history of playing MMORPGs, like World of Warcraft. I was even a rather hardcore raider – or in other words, a participant in high-end end-game content, the most challenging stuff saved for the most dedicated players. The way WoW designed its encounters was interesting, chaotic, engaging, and often quite complicated. However, I rarely felt the sense of intuitive sensibility I feel playing Final Fantasy XIV. The narrative and aesthetic building blocks of combat in Final Fantasy are all abstractions of actions one can make some sense of in the context of the fiction. WoW, at least when I played it, had some of that, but its more difficult encounters leaned much further into abstraction, with status conditions upon gameplay modifiers upon unique interactions disconnecting, at least for me, the experience of engaging with those systems from the experience of being in the fantasy world.

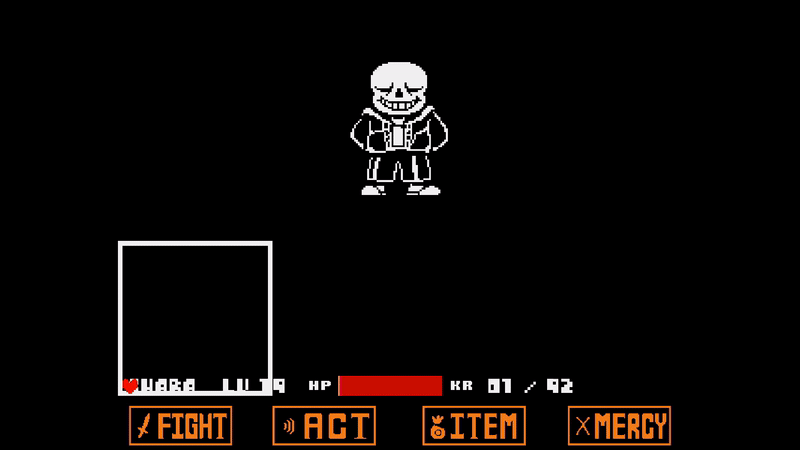

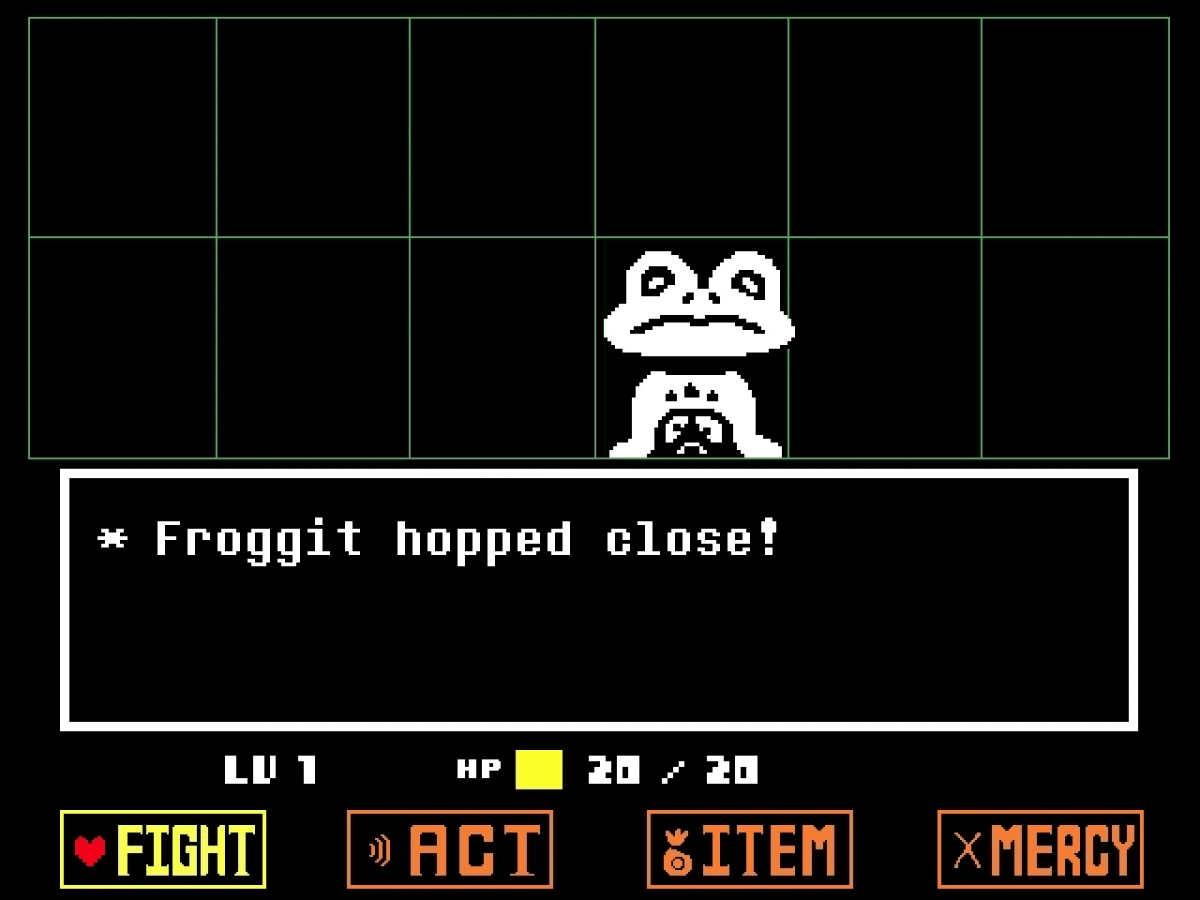

I have been playing quite a bit of Undertale and Undertale-adjacent content, lately. Such as Toby Fox’s other brilliant game Deltarune, and the charming fan-made Undertale prequel, Undertale Yellow. While dodging bullets shaped like flexing muscles, representing a monster’s outgoing personality, it occurred to me how starkly similar these two games – Final Fantasy XIV and Undertale actually are, at least in terms of their combat systems.

Okay hear me out, I’m not insane, I swear.

Both games are RPGs that represent enemy offensive actions with abstract shapes that denote areas on a 2D plane of danger, and safety. Entering a “danger zone” causes the player damage. The shapes these danger zones take abstractly denote the kind of action the enemy is taking. In Undertale, these danger zones are called bullets, and if they’re shaped like water droplets, they might denote the enemy crying, or causing it to rain. In FFXIV, these danger zones are called AoEs, and if it’s a cone extended from a monster’s front, it might denote the monster breathing fire.

I can see you’re not sold. Alright, consider this; both games feature two prominent methods by which tension, challenge, and surprise is weaved into gameplay. In Undertale you might run into a monster who cries tears down on you from above that you have to avoid. Then, you might run into a monster who sends a fly to slowly follow you, which you must constantly move away from. Neither bullet pattern is especially difficult to dodge. But then, you may run into both monsters simultaneously! Suddenly, you must multitask and interweave devoting attention to both bullet patterns at once. In Final Fantasy XIV, boss mechanics are deployed in a very specific way. Every boss will start by using one of its signature abilities – perhaps a simple barrage of AoE attacks at random locations around the players. Then, they’ll introduce a new mechanic, maybe forcing the players to a certain quadrant of the arena while looking in a certain direction. Neither pattern is especially difficult to dodge. But then, the boss will begin using both moves simultaneously! Suddenly, you must multitask and interweave devoting attention to both patterns at once.

Oh HMMM sure looks *exactly* like AoE markers and color-coded attacks with special rules, HMMM!

That is not where the similarities end, though. The other prominent method by which both games influence their interest curves is through the introduction of new rules, as previously mentioned. Think about it; The first time Undertale deploys the “blue heart” mechanic, the player is shocked, possibly confused, as their schmup-style 2D grid of bullet dodging suddenly becomes a 2D platformer complete with gravity and jumping controls. It completely upends the paradigm of how one must think of the spatial relationships of all entities in play. I really think the “blue heart” moment is undersold in how instantly it establishes Undertale’s playful nature, and the breadth of unique variety it is willing to explore. Meanwhile, in FFXIV, the first I remember of an equivalent “blue heart” moment is when I was introduced to the “ice floor” mechanic in the story content leading up to FFXIV’s first expansion. The ice floor forces the player to move a set, (large) minimum distance, if moving at all, most often coinciding with other, damaging mechanics that need to be dodged. This, and other mechanics like, “forced march”, which, as the name implies, forces your character to march in a straight line, changes the paradigm of how you relate your character’s spatial relationship to all other entities in play.

But perhaps I give Undertale too much credit. I am not, after all, extremely familiar with the shoot ’em ups and bullet hells which inspired it. In fact, it feels as though bullet hell-like mechanics have been infiltrating other genres for a while now, much like RPG mechanics started to do some years ago. I’m always in favor of that sort of diffusion, as it leads to a lot of cool new ideas that couldn’t exist otherwise. It reminds me of Returnal, or its inspirations like Nier and Nier: Automota. I do, however, think there is a certain something to how FFXIV and Undertale/Deltarune play with their rules, that *does* set them apart from other similar games. I just can’t shake the feeling that these two seemingly disparate experiences have a strong link between them.

Rules

Image unrelated.

These “paradigm shifting” moments are essentially the introduction of supplementary rules to the basis upon each respective game is built. Games are made of rules, so when you add rules, you change the game. Both Undertale and Final Fantasy XIV do this with some regularity, to the point that adapting to the addition of new rules is a prominent part of both games’ core skillset and identity. A combination of pattern recognition, rote memorization, and intuitive anticipation replaces the twitch-reactive mindset you might find in an action game. This settles both games into a certain mood, where anything can happen, because any new rule can simply be dropped in the player’s lap.

By utilizing intuitive design, presumably through extensive testing, FFXIV dodges the obvious pitfall of such an approach in most cases. That being, if a player settles into the loop of a comfortable and reliable ruleset, a sudden disruption can feel jarring and unfair – a new rule kind of implies that the player hasn’t been prepared for it, yeah? So that’s why it’s so essential to this sort of playful design that things always be intuitive. FFXIV has several vectors to achieve this – not just in its flashing indicators, AoE warning shapes, monster designs, and monster animations, but also through the text displayed on enemy UI when they use a special attack. “Forced March” sort of implies what it does, and those words are visible to you before you have to react. All these things form the language by which FFXIV communicates information and teaches you each new rule without teaching it to you. Undertale’s language for communicating new rules is through shapes. When the player’s heart turns green, the game becomes a bit of a rhythm-adjacent directional timing game. This is indicated by all the enemy bullets becoming arrows, and moving in regular intervals with the music.

As you can see, once this stuff starts to stack up, it can really get quite taxing. Gif from here.

In both cases, if players are ever confused, they are never confused for long, and even may discern the nuances of a new rule before it’s engaged! Understanding game rules becomes a skill in itself, and experienced players are encouraged to discern the shape of the design through intuition. I find something so fascinating and appealing about this because it goes in the opposite direction of the typical wisdom that the hand of the designer needs to be invisible. The players play along as the designer plays – it creates a sort of Calvinball mentality, where the game can be anything you imagine, and every encounter can feel fresh. So many other RPGs I’ve played get so wrapped up in what the design of their encounters must be that they feel stifling.

I think this is what makes me distinguish Undertale and Final Fantasy XIV so closely in my mind, even compared to similar games in the MMO or Shoot ‘Em Ups genres. It’s the playfulness, the bending and manipulating of the very fabric of the game by bending, reimagining, or supplementing the very building blocks, the rules. This allows the designers so much freedom in what they can convey simply through combat mechanics, and if you’ve read anything of mine or spoken to me for five minutes, you may know that I love when gameplay and narrative synergize or better yet supplement one another. Undertale uses shapes to communicate gameplay obstacles, but also the shape of the opposing monsters’ emotions. The blue heart mechanic only appears while fighting the skeleton brothers, two fights that happen worlds apart but are connected by this, emphasizing their relationship to each other. When a character repeats the use of a forbidden power in Final Fantasy you hadn’t seen for a very long time, you understand their desperation. And so on.

All that aside, you’ll still find me looking like this standing in a basic-ass AoE

What Was I Talking About?

Anyway, I think I’m finally satisfied with what was causing an itch at the back of my brain while playing Undertale Yellow. It’s that the exact same parts of that brain, the same reflexes, pattern recognition skills, and adaptability I had trained in Final Fantasy were carrying over. And I think I’ve been able to suss out what about the two games feels so familiar to me. Playfulness in design, the willinging to recontextualize and reorient the ruleset has been employed often in games, but rarely is it such a central pillar as it is in Undertale and FFXIV. Wario Ware and Mario Party are games about playing smaller, bite sized game experiences, and I’ve heard FFXIV players joke that they’re essentially the same as their favorite MMO. I can remember a number of arena battles in Ratchet and Clank that randomly swap out your weapon, or give the enemies some absurd advantage, rotating rules in and out over time. I think I’ve found a lot to take away from this exercise, and it’s given me a deeper appreciation for the very different approaches there are to making combat in games both fun and engaging. Not everything has to be about fast and snappy reactions. There are a myriad of reasons a person might enjoy a game and a thousand avenues to accentuate that. So experiment with your design and your rules, and see what speaks to you.

So – let us be about it, hero.