I’ve had some stuff on the brain lately, in regards to difficulty’s place in design, which is what tends to happen when you play Elden Ring for so many hours straight. I’ve also been replaying Toby Fox’s Deltarune with a friend, another game that uses difficulty in interesting ways. I’ve had this thought for a while, to do a write up about how difficulty can be, and is, deployed in design to affect the greater experience. This article contains major spoilers for Undertale and mild spoilers for FromSoftware’s Elden Ring.

To be unambiguous here – difficulty is a very nuanced and at times personal subject in design that touches on a host of other things such as game balance, technical depth, general play enjoyment, and of course accessibility. These are very complex subjects that deserve their own discussions. What I’m specifically focusing on in this article is how difficulty can be deployed with purpose, and often has more relevance to the overall design than is often attributed to it, as a simple measure of player competence for the purposes of challenge. I wanted to look at an example of a game where difficulty is an intimate part of its narrative design, where the reactions it illicit is very much a product of how difficulty is utilized.

The idea that difficulty in gameplay can be a narrative tool should be fairly straightforward to grasp when looking at a couple of examples. In Elden Ring, all of your primary boss characters are demigods, children of gods, who once fought over the shards of the titular ring. The demigod Radahn fought his half-sister Malenia to a standstill. Radahn is oft touted as the strongest of all demigods – he holds the stars in stasis by his own power – he takes an entire platoon of elite soldiers in gameplay just to take down! This assertion that Radahn is the strongest remains more or less unchallenged for some time. There are harder bosses, but none that require so much backup to defeat, nor any nearly as hobbled with injury as poor Radahn.

There is a secret and hidden boss, however, another demigod called Malenia, who is still alive. When Radahn is found, Malenia’s power, the same power that has scarred the landscape around Radahn has left him ‘divested of his wits’, and fighting like a wild animal. Malenia, however, is more or less totally lucid, angrily awaiting the return of her missing twin brother and liege lord, Miquella. Malenia has never been in better form – there was nothing stopping her from taking Radahn’s shard of the Elden Ring and yet she did not, so clearly she has no interest in ruling. Indeed her dialogue reinforces the notion that she fought only for loyalty to her brother’s ambitions.

Any who’ve fought Malenia will tell you, the idea that Radahn could stand a chance against Malenia in combat, is laughable. They could tell you entirely because of how demanding of a boss she is, how difficult she is tells you the entire story. There’s no possible way she left her encounter with Radahn in defeat, or even in a draw. Her swordsmanship is deadly and near insurmountable, and she hides an even greater power beyond that. She defeated him, and he was left without his senses. She must have left because her brother, the real aspirant to the Elden Ring, went missing. The player will know this intuitively, through experience. They lived it. They will feel it in their bones. Radahn could not have defeated Malenia, and the rest of the story follows. Without Miquella, there would be no reason to collect Radahn’s shard. If you’ve explored the world of Elden Ring thoroughly, this line of thinking is vindicated, as you’ll know Miquella underwent a sudden and shocking disappearance, followed by an extended and secretive absence.

If you’ll indulge me to invoke the first of two quotes from Bennett Foddy, designer of Getting Over It With Bennett Foddy, a notoriously difficult game.

“The act of climbing, in the digital world or in real life, has certain essential properties that give the game its flavor. No amount of forward progress is guaranteed; some cliffs are too sheer or too slippery. And the player is constantly, unremittingly in danger of falling and losing everything.” – Bennett Foddy

All that said, difficulty is not just a mechanical gameplay consideration. Like all aspects of a game, it is an essential part of the cumulative experience. I am of the opinion that if an obstacle within your narrative is meant to be threatening, formidable, out to kill our dear player character, then the player should get the sense that this force is threatening and formidable. To trivialize it, or deny the sensation that there is an opposing force trying to halt the player’s forward motion, is to render the narrative dishonest, and rob it of its power. If conflict is about power, than difficulty is one of the most genuine ways power can be communicated in an interactive system. This isn’t to say that every game needs extreme challenge, or even that every game with conflict is necessarily trying to create the aforementioned sense of opposing force. This is but one type of experience you might seek to create, a goal your art may aspire to. In fact, this is just one way to deploy difficulty as a mode of narrative design. That brings us to Undertale.

In Undertale, the story is persistent – and any runs of the game, even when reset, are remembered and color the experience of playing Undertale going forward in little ways. Death and resetting is diegetic, meaning the player character is literally dying and coming back to life at a previous point in time, within the game’s fiction. In this way failure is kind of inherently tied to the narrative. Undertale comes packaged with a few predefined paths to play that present themselves based on how the player tackles obstacles. Killing monsters casually as they come to confront you will result in one of several ‘neutral’ endings, in which the player’s human character escapes the world of monsters, which is left in varying states of disarray as a result. The ‘pacifist’ run will see the player avoiding lethal violence, and reaching out the hand of friendship to major characters to achieve the best world for everyone. The ‘no mercy’ run is the third and most obscure path, in which not only is lethal force deployed against all obstacles, lethal force is deployed against every potential obstacle, wiping out all monsters in the underground.

To do this, the player has to spend an inordinate amount of time trawling around for enemies to fight. Every single one needs to be killed for the No Mercy ending to hold true. This process is long, repetitive, somewhat dull, and even grueling at times. And yet, it remains an immensely popular way to play this already immensely popular game. There is a purpose to all this consternation, though. I think it pretty noncontroversial to say Undertale‘s ultimate message is one of nonviolence – that the best way to solve conflict is through open communication and a curious, empathic heart. The No Mercy run exists as a counterpoint to this message, to prove its efficacy. Killing everything in Undertale is a pain, frankly. It takes a lot of effort but not necessarily the kind of effort a player seeking challenge might be after. More of that exists along the less violent story routes. No, Undertale is instilling through the avenue of frustration that ‘the easy way out’ isn’t always easy, and while ‘the high road’ isn’t always easy either, it’s a heck of a lot more fun than willful cruelty, which is a continuous and conscious effort on the part of the abuser.

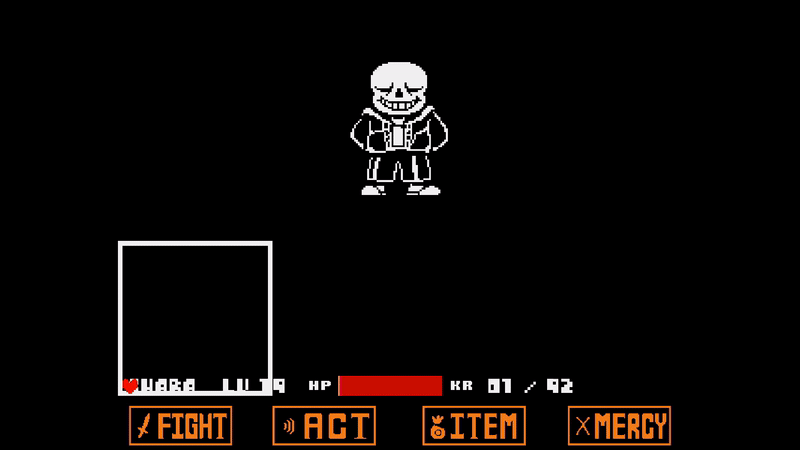

And yet, most playing through will persist. They have buy in, and as Undertale expects, most will be curious enough to want to know what happens next, not in spite of the frustration, but perhaps even because of it. One of Undertale‘s most infamous features is the normally comedic, friendly, and jovial character Sans, who is a bit of an internet meme. There’s a lot of reasons for that, but I think one of them has to be his sudden transformation into the game’s greatest and most stubborn challenge. The boss battle against Sans, with one other exception, is the only real challenge in the No Mercy run, with all other opposition crumpling like paper before the player. The player has not had a ramp up in difficulty in this point, and Sans comes out of the gate swinging with one of the most demanding gameplay experiences in modern popular interactive media. No punches pulled here, Sans is meant to be a brick wall of a boss, one that will have to be worn down with patience if it’s to be cleared at all.

Fans of Undertale have such a personal relationship with it, and given its immense popularity that is quite impressive. The player at this point, is acting as an agent within the narrative, separate and apart from their controlled character, Frisk, who ambiguously is either mind-controlled by the player, or influenced by the player subtly to act or fight. Sans tries everything he can to appeal to the player to start over, to do anything but follow through on the path they’re on. He pleads, he appeals to humanity, he threatens, and he even cheats. After each failure, Sans comes up with some new unique dialogue with which to taunt and belittle you for trying. The player can come back as many times as they want to try again, so words and his ability to act as an immovable object are Sans’s only real forms of power over you. The ironclad stubbornness of this encounter, the unerring, unflinching confidence in its unreasonableness makes it feel real, like Sans is a thinking actor specifically trying to get under your skin, and make your goal unreachable, and that is what makes it feel personal.

Sans isn’t trying to kill you – he knows that is beyond his power. He’s trying to wear you down, to frustrate you, to bore you, whatever it takes to make you give up on your killing spree, and maybe start over, or even give up. The story was very carefully set up to make this a legitimate way to cap off the narrative. In Undertale, the story is persistent – and any runs of the game, even when reset, are remembered and color the experience of playing Undertale going forward in little ways. In Undertale, giving up and starting over is a legitimate and designed-for chapter of the narrative.

Giving up can mean a new beginning, a world where the player is not a force for destruction and misery, but a force for change and friendship. Whenever I play Undertale, I love to play the part of the sinister player destroying the world and its inhabitants for callous entertainment (and in a way, I truly am that), but then our protagonist, Frisk, overtaken by sorrow after killing Sans, is able to wrestle back control and ease me into a more peaceful, and ultimately more fulfilling world. I’ll play a No Mercy run just up until I’ve killed Sans, and no further. I’ll then roleplay the regretful monster, the powerful demon whose lost everything, and has no more mountains to conquer. From there I return, back to the beginning of the game, anew with a desire to learn and try again. Undertale makes failure an avenue for learning and improving at the game yes, but also a potential narrative moment of fulfillment.

I love this scenario. It creates a full arc for me, as the will and intention of the player character Frisk, to go through. It’s a rich narrative that unfolds entirely through gameplay that I get to be a part of. That’s the real magic of difficulty in games for me, it’s something entirely unique to the medium, a level of interactivity other forms of art simply cannot achieve. Sans is blisteringly difficult, to the point that he may even feel antagonistic to the human behind the screen. But the game isn’t trying to punish you, nor look down on you, it’s trying to play with you. It is a game, after all. It is interactive theater, a stage show where you are the star. And maybe just maybe you’ll get something valuable out of the experience.

“Death and rebirth, trying and overcoming—we want that cycle to be enjoyable. In life, death is a horrible thing. In play, it can be something else.“-Hidetaka Miyazaki

You are meant to be along for this emotional ride through joy, through sorrow, through fear, through love, through distress, and yes, through frustration. It’s a frustrating thing to be denied passage, to face an opposing force that’ll do everything in it’s power to stop you. If the art is to be evocative, it may be necessary to instill that sense of frustration. I will deploy the second of two Bennett Foddy quotes, as I admire the way he puts it;

“What’s the feeling like? Are you stressed? I guess you don’t hate it if you got this far, feeling frustrated. It’s underrated. An orange, a sweet juicy fruit locked inside a bitter peel. That’s not how I feel about a challenge. I only want the bitterness. It’s coffee, it’s grapefruit, it’s licorice.” – Bennett Foddy

Frustration is not the opposite of fun. I think the runaway success of games like Dark Souls, Elden Ring, and Undertale, games that very much use frustration as feature of their storytelling, are strong evidence of this. There are hosts of games that follow similar patterns. When you play and watch people play difficult games as much as I do, you begin to notice that not only is frustration not a deterrent to the fun for most, it often accompanies the highest highs of player’s positive emotional reactions. Art is not a vehicle for merely delivering joy and nothing else. Life is a rich tapestry of a variety of emotions, and if art is to speak truth, then I think it’s worth considering how best to accurately reflect that. I’ve been talking a lot about feelings and emotional reaction, and I can’t overstate how subjective such things can be. You’re walking a fine line when utilizing traditionally negative emotions such as frustration to tell a story. As I said before, difficulty is a very nuanced and complex topic and this is just one aspect of it, one feature of difficulty to consider when configuring the shape of the experience you want to create. Difficulty can be used to tell and legitimize interactive narrative in a very profound way. That said, not all games need to, and by no means should they, take the same shape. Knowing how best to achieve the goals of your design starts with understanding your goals, and understanding the tools at your disposal.

You have something called ‘determination.’ So as long as you hold on… so as long as you do what’s in your heart… I believe you can do the right thing…