Alternatively: “What The Heck is ‘Floatiness’ and Is It Ruining Kingdom Hearts? I Settle it Forever“

‘Floatiness’ is the extremely scientific term that parts of the Kingdom Hearts fan community have adopted to refer to a sort of shift in how some of the more modern and spin-off Kingdom Hearts games feel to play, as opposed to their predecessors. I’ve seen this term come in and out of vogue when it comes to in-depth and armchair analysis of Kingdom Hearts‘s combat, but it’s always fascinated me. I’m going to try to define what this somewhat nebulous term is specifically referring to, and how it’s been supposedly creeping its way into one of my favorite action RPG franchises. What causes floatiness in particular? What is the greater context of design which is causing whatever this ‘floatiness’ is to happen? Perhaps this exercise can help us explore the often imprecise art of ascertaining gamefeel in general. I certainly hope so.

First off, we’ve got to define it, this floatiness. Informally, it is reported as the sensation that the Kingdom Hearts player character lacks weight, impact, and to my interpretation, immediacy, or some combination thereof. For those unaware, Kingdom Hearts is a series of action games with a particular emphasis on exaggerated, superhuman feats of acrobatic melee combat, favoring style, spectacle, and emotive action, akin to combat-heavy anime and manga. All that while immersed in a fantasy world full of Disney characters, Final Fantasy characters, and a unique dream-like fictional mythology of its own. Trying to define this term will be much of what this article is seeking to accomplish.

With combatants consisting primarily of magical swordsman and dark wizards, while borrowing aesthetically from classic Disney animation, Kingdom Hearts offered its players a combat system increasingly free of the bounds of gravity, allowing its player characters to bound meters into the air at a time, maintaining that airtime through continued swinging of their sword, with a cartoonish sort of physical logic.

So, all this in mind, I set out to compare the gamefeel of several Kingdom Hearts games in my own experience to try and get a better idea. To make this process somewhat more precise, I investigated what is by my estimation one of the key metrics in determining the gamefeel of an action combat system – the timing of the primary attacks. Every action in a game as visually rich as Kingdom Hearts and its sequels has a startup time and ending lag. The former is the real-time between the player’s button input and the resolution of the action they’ve input, the latter is the real-time between the resolution of the action, and when the player’s next input can be resolved. For example, if a player character is to swing a big hammer, they’ll push the swing hammer button. As their avatar lifts the hammer with a grunt and struggle to convey its weight, we have our startup time, and as he pulls the hammer back to his side after the big swing, we have our ending lag, with the avatar unable to run or jump while resetting the hammer, in this example.

Now imagine the hammer is a comically oversized key and you have a pretty good idea of what we’ll be measuring. Floatiness became an almost absurdly hot-button topic among Kingdom Hearts diehards due to its relationship with the much anticipated Kingdom Hearts 3. As the successor to the beloved Kingdom Hearts 2, and first numbered entry in the series for a period of thirteen years (though by no means the only Kingdom Hearts game to release in that period), a lot of anticipation was placed upon what the game would feel like to play. Its gamefeel, so to speak. Kingdom Hearts 2 has stayed in many people’s hearts as an all-time favorite action game due to the smoothness of its combat system, as any fan would tell you. So comparisons were inevitable. The stakes were high.

Kingdom Hearts 3, despite being the best selling entry in the series, gained a healthy amount of criticism from long-time fans in regards to its gamefeel. Floatiness was oft invoked. The developers seemed to take feedback from hardcore fans seriously, as the game would be later patched in key ways to increase speed and fluidity of the gameplay. More on that later. So what’s the truth? Has floatiness ruined Kingdom Hearts forever? Are we doomed to forever circle the drain of game design discourse without knowing what on earth we’re actually talking about? I’ve spoken to friends who know how to use a computer and they allege that numbers are involved here, believe it or not. So I’m afraid I have no choice but to deploy the diagram.

Data World

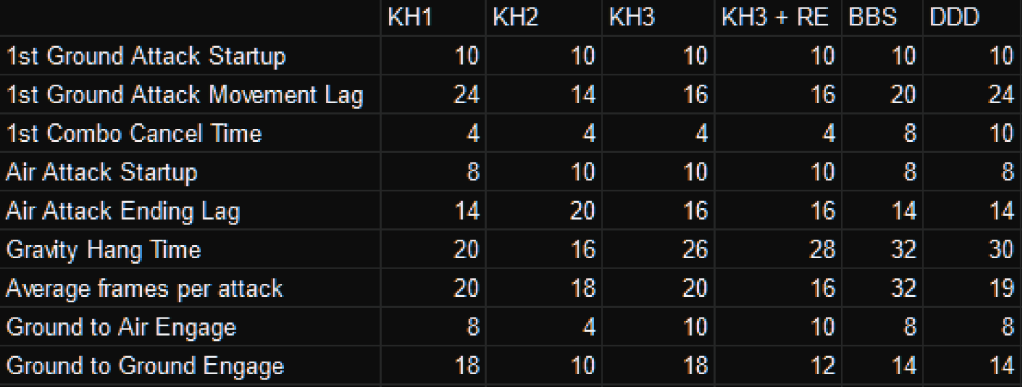

First let’s define some terms. All footage I used for this analysis is from the Final Mix, 60fps versions of the games, captured on a Playstation 5. All values are measured in animation frames. For the sake of consistency, in each game I tested the animations of main player character Sora or his closest equivalent (In Birth By Sleep the resident Sora-like character is named Ventus, but he’s close enough and for our purposes we’ll consider him a “Sora”). The games I will be looking at are as follows:

Kingdom Hearts

Kingdom Hearts 2

Kingdom Hearts 3 pre-“Remind” patch

Kingdom Hearts 3 post-“Remind” patch

Kingdom Hearts: Birth By Sleep

Kingdom Hearts: Dream Drop Distance

“Startup” here is defined as the time between Sora beginning an attack and that attack “resolving”, here defined as the moment his weapon crosses in front of his body. “Ending lag” is the time between an attack resolving and when Sora can move again, no longer committed to the attack. “Cancel Time” is the time it takes before Sora’s first attack can be interrupted to perform his second combo attack. “Gravity Hang Time” is the amount of time between an aerial attack beginning and when Sora reaches his maximum falling speed. More on that later. “Engage” here means the time between inputting an attack and when sora can strike a distant enemy from a neutral position.

So these results are pretty much in line with what I expected going into this project. KH2 is the fastest game, KH1 is second fastest. BBS and DDD are dead-last, KH3 is about in the middle, while KH3 with its post-launch patch just a little bit faster than that.

Some surprises:

Every KH game seems to have the exact same startup time for the first most basic attack of a combo. Seems like they’ve been pretty happy with this one from the word ‘go’ and consistently on from there.

KH1’s movement lag from a grounded attack is insanely long, as long as DDD’s. KH2’s is way faster, and nearly the same as KH3’s.

KH1, KH2, and KH3 all cancel their first attack into an attack combo incredibly fast at just four frames, another astonishing level of consistency, although BBS and DDD combos take twice as long or more to come out.

KH2’s biggest advantages in speed are its gravity hang time, and time to engage enemies. KH3’s gravity hang time actually got worse with its post-launch patch, though not noticeably, and this has to do with a new attack added in the patch that has a longer animation in general.

BBS and DDD don’t do too badly in the enemy engagement department, better than KH1 and KH3 pre-patch, even. KH2 is still the champ here, but this fast engage time might be a saving grace for BBS and DDD.

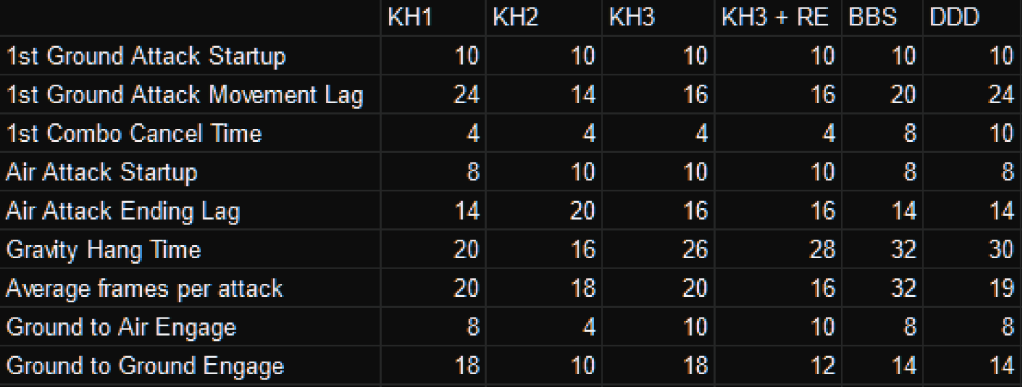

There is a lot to talk about, so I’ll drop the chart here again real quick, just because I know you all wanted to look at it again.

Okay, So What Is It?

What’s what? Oh! Floatiness. What is ‘floatiness’? My hypothesis going into this was that it’s tied up with the aforementioned startup and ending lag statistics, which would have a huge impact on the speed of the game. Kingdom Hearts: Birth By Sleep, Kingdom Hearts: Dream Drop Distance, and to a lesser extent Kingdom Hearts 3 are somewhat known among hardcore fans as the ‘floatier’ games, the former two by far the most guilty. I had presumed that in gathering my data, it would bear out that those two games would have the higher numbers when recording the delays, lag, and hang time. Kingdom Hearts 2 would be the fastest game, only slightly faster than Kingdom Hearts, and Kingdom Hearts 3 would fall somewhere in the middle. Indeed this was the result. So. Case closed? Shorter periods of loss of character control equals better combat? Probably a little more nuanced than that.

Golden calf Kingdom Hearts 2 absolutely has the advantage over its successors and predecessor when it comes to attack commitment. Its startup times, ending lag, and combo speed are universally faster across the board. But… they’re not that different from KH1 and KH3, even pre-patch. Almost immediately when I started this experiment, replaying each of the games side-by-side I came to realize the nuances of how gravity works in each game.

The Gravity Situation

As the Kingdom Hearts series progressed, aerial combat became more prominent. I always imagined in my head that the first Kingdom Hearts game was “the more grounded one”. And it kind of is. In the first game, attacking launches Sora high in the air toward aerial targets, and repeated attacks can keep him airborn somewhat. Kingdom Hearts 2 pushed this much further, with far more automated and accurate tracking on enemies, pushing Sora high into the air with each attack. I was kind of shocked to find that in Kingdom Hearts 2, the game I associate most with air combat, gravity is much more powerful than it is in any other game. With a delay of only 16 frames in KH2, compared to KH1’s 20, and double that at 32 frames in BBS, KH2 by far is the most beholden to gravity when the player is not attacking. This makes gravity a function of the player’s inaction. Never are they airborne without making it a conscious decision. In BBS and DDD, being strung up in the air against your will is almost the norm. There is a huge delay between aerial attacking and being affected by gravity.

I think this is a major piece of the floatiness puzzle too. Being on the ground in these games naturally gives you a lot more options. You have access to your dodge roll. You are able to more precisely place yourself for things like blocking, or jumping out of the way, or lining up the right attack. Simply, being in the air is advantageous in some ways, but also a lot more risky. In the less ‘floaty’ games it feels as though being airborne is always a conscious choice, whereas the others place you there in spite of the player, and leave Sora hanging in a risky position for far longer than a player might intend. The ability to get back to the ground quickly gives finer control over the player’s risk vs. reward, and the game forms a more solid and consistent relationship with that risk vs. reward.

Gamefeel Good

The title of this article mentions gamefeel, so I’m going to take a moment to discuss that. Like ‘floatiness’ this term is a little hard to pin down, so, uh, how about wikipedia. They seem to know everything.

“Game feel (sometimes referred to as “game juice“) is the intangible, tactile sensation experienced when interacting with video games. The term was popularized by the book Game Feel: A Game Designer’s Guide to Virtual Sensation[1] written by Steve Swink. The term has no formal definition”

Wikipedia Article on Game Feel

Well that was absolutely no help whatsoever. Wikipedia cites input, response, context, aesthetic, metaphor, and rules as the features a game can change to influence gamefeel, and this seemingly comes from Mr. Swink as well. It’s as good a place as any to start, so let’s see how this applies to our floatiness dilemma.

I don’t want to get too into the weeds with these, so I’ll limit my observations to response, metaphor, and rules. Suffice to say I think KH does pretty universally well in the input and aesthetics department. Context is a bit more nuanced, but again, trying to limit our scope here.

Let’s be a little contrarian and try to make at least a very small part of this gamefeel equation tangible. We’ve already broken down that there seems to be a correlation between the delay between action and reaction in Kingdom Hearts, and the popular perception of how well the games feel to play. KH1 and KH2 are beloved with their snappy reaction times, KH3 is well liked but garnered a lot of fan feedback. BBS and DDD are liked but not necessarily for the fluidity of their combat, and I rarely see gamefeel cited among their strengths. The data easily illustrates the importance of response time as a variable.

The metaphor at play here is how the timing of attacks translates to what the game is trying to convey. The main thing the mechanics of KH is trying to convey is melee combat. All these varying measures of time and attack resolution and ending lag etc. is all metaphor for the physicality of swinging a sword at a guy. A real person cannot instantaneously move their arms, the sword has startup time and ending lag in real life. That’s why these time gaps are there in the first place. It wouldn’t be a very fun game if you pressed the attack button and just instantly won. So as in a real, actual battle, you have to consider how your various actions leave you open to counterattack. On the other hand, one can go overboard with this, as in real life you’re also trying to minimize your vulnerabilities, and a swordsman is not going to be flashy at the cost of leaving himself open to a hail of enemy attacks. These are things people intuitively understand, and so players bring with them preconceived notions of how entities should behave in these situations.

Drill even further down and you get to the rules of the game itself. Enemies are attacking you, while you’re trying to attack them. If you are locked into an animation you are unable to deploy any defense to stop them, and so we have a game. Risk, and reward. However, if the player’s control feels disconnected from how these rules operate gamefeel is thrown off. In Birth By Sleep and Dream Drop Distance, attacking creates great gaps of no-player time, where inputs on your controller mean nothing. You are vulnerable to attack, and a passive observer in the world. This disconnect throws off both the player’s relationship to response and to the rules of the game, as overly long and committed attacks can become more of a liability than an asset. In KH1 and KH2 throwing out attacks is almost always fun and satisfying, and usually rewarding. It’s often a lot more burdensome to do so BBS and DDD. BBS and DDD have other methods of dealing damage besides the basic attack, but since the basic attack is so pivotal in the main series, a lot of players are thrown off by how minimized it is in these spin off titles, which primarily utilize the command deck instead.

The Command Deck

So why is Birth by Sleep and Dream Drop Distance so damn slow compared to their peers? Well these two games share two very important elements in common. First, they were each developed for a handheld family of systems. Second, they share the game design system known as the command deck. These two points of similarity are very much entwined.

Kingdom Hearts and its two numbered sequels utilized the ‘command menu’, a little persistent menu in the corner of the screen that can be navigated in real time to select whether you want Sora to attack, use an item, or cast a magic spell, essentially. 90% of the time you will be spamming the attack button. The command menu was meant to evoke the strategic decision making of a turn-based Final Fantasy game, but re-tuned for an action combat context. Ultimately contextual combo modifiers became a much greater source of player expression in gameplay, and the strategic applications of the command menu are limited. However, it remains an elegant way to give the player a lot of options without bogging the game down with too many buttons.

When Kingdom Hearts went handheld it rethought its combat. Suddenly, we’re dealing with a much smaller screen, and the camera had to be pulled in on the player character to compensate. As a result, enemies can much more easily hit you from off-screen or sneak up behind you. Consideration was clearly given to a system that better fit playing on the go, where deep concentration on twitch-reaction may not be as viable or palatable. The command deck was the answer, a cooldown-based system where actions are selected from a rotating list and can be used at any time. Now the flow of combat is dictated by these ability cooldowns, and the regular attack combo was made to be more slow-paced, flashy, less freeform, and yes, more floaty so as act more like a stopgap to using the command deck, rather than the main form of attack itself. The command deck has a lot of advantages such as the ability to customize your attack loadout in a much more granular way, but it also has its own host of problems, which I won’t get into here.

The point is, Birth by Sleep and Dream Drop Distance are deliberately slower games made so because they were designed to be played on the go, and utilize entirely new systems that weren’t designed with KH1 or KH2’s speed and flow in mind. Because KH3, BBS, and DDD share a lot of development talent though, it seems like a lot of the design philosophy of these handheld games bled over into KH3’s headliner console game, which was jarring for a lot of people.

Okay So… Is This Bad?

In my opinion, one of Kingdom Hearts‘ greatest strengths is the immediacy and responsiveness of its gameplay. A fine degree of control gives the player a much wider spectrum of possibilities in any given scenario, and this is what leads to a creative space within gameplay for players to express themselves through the gameplay. This fluidity also allows disparate gameplay mechanics such as movement and sword attacks to blend. Kingdom Hearts 2 always feels as though its many, many mechanics are in a harmonious conversation with one another. Engaging a ground enemy can be converted into an aerial assault, which can flow into a strategic repositioning, etc.

So yes, I think it weakens Kingdom Hearts‘ identity somewhat when some of the more experimental entries in the series have dabbled with slowing down the combat and making its pieces more discrete. The particulars are a bit beyond this already enormous article, but I did want you to understand my motivations for trying to understand how and why Kingdom Hearts 2 feels so different to play than a game like Kingdom Hearts: Birth By Sleep.

Kingdom Hearts is a series about ridiculous anime battles between magical wizards wielding baseball bat-sized keys as weapons. People fling themselves through the air to attack one another. It’s not realistic, but it exists within the heightened reality realm of animation. Its primary inspirations are, after all, some of the animation greats, including Disney of all things. Animation works to heighten reality because it has an understanding of its underpinnings. Even if people can jump twenty feet in the air, there still has to be a since of presence and weight. It has to give the impression that some sort of underlying laws of physics are at play even if they aren’t one-to-one to our own laws of physics.

Despite appearances, it wasn’t a magic genie spell that made KH2 so satisfying to play. It was hard work, clever planning, likely some very precise number tuning, and likely a whole lot of playtesting. I want to know the nitty gritty of what made Kingdom Hearts one of the smoothest action games in existence, what distanced it from that, and what brought it closer to that esteem once again. Because you see, there are still those Kingdom Hearts 3: Remind post-launch changes to talk about.

Kingdom Hearts III And The Combo Modifier

In Kingdom Hearts, Sora has a very basic attack combo, with little by way of alternate options for the player, at first blush. You press the attack button, and sorry does the next hit of the combo. Rinse, repeat. The wrinkle though, is that Sora can gain abilities which cause his attack combo to behave differently depending on where Sora is standing relative to his target.

Kingdom Hearts 2 pushed this contextual combo modifier idea much further, with hosts of new options that allowed the player to flex mastery over the system through mastery of manipulating these contextual attacks. They did things like make engaging enemies faster, extending the combo, increasing the power and range of combo finishers, among other things.

Kingdom Hearts 3 launched with its share of combo modifiers, but they lacked the breadth and applicability of KH2’s abilities, and they did little to speed up combat overall. That is, until it was patched in anticipation of the Kingdom Hearts 3: Remind DLC. Numerous combo modifiers were added which increased the overall speed of Sora’s basic combo attack and made the game feel overall more responsive. I don’t think the Remind DLC gets enough credit for just how much it improved, and it’s kind of refreshing how in tune it is with popular feedback. Real people playing your game can tell you a lot about that mystifying, all-important yet elusive gamefeel.

Airstep is Literally a Game-Changer

Kingdom Hearts as a series has done a decent job with teaching players about its systems and how they work. Some of the more advanced mechanics that deepen higher-level play are a bit more obscure, but usually reaching a baseline level of competency at core systems is pretty straightforward. Kingdom Hearts 3, however, I found stumbled at instilling the importance of oce of its most important new mechanics, the airstep. The airstep allows the player to manually aim the camera toward a distant foe, and fling Sora at them at high speed for a relatively quick engage across a huge battlefield. This was obviously done to compensate for the much larger environments featured in KH3 as compared to older games, but utilizing this move frequently and often, even in close quarters, really does change the way the game is played.

Airstep can cancel out of nearly any other action, you see. In terms of making the game more fluid, or moreover in terms of giving the player fine control over their actions, the airstep affords an enormous amount of power and precision to determine the pace of fights in Kingdom Hearts 3. This along with the ability to cancel combo finisher attacks, which was added in the Remind DLC update, makes the whole combat a lot more cohesive and much more fluid than you might initially expect based on the raw frame data. Speaking of which, the frame data was improved in that update as well! The fact is that this latest iteration evolved the combat in a lot of interesting ways that I don’t want to see abandoned in favor of just making the series going forward exactly like everything that came before.

Kingdom Hearts Is Doing Fine, Actually (But It Can Do Better)

So yeah, when people say Kingdom Hearts 3 feels ‘floaty’ as compared to Kingdom Hearts and Kingdom Hearts 2 the evidence is there. Attacks are less responsive and more of a commitment, generally, and gravity is turned off more liberally. You will literally find Sora floating more without direct player intervention. However, the frame data differences, discounting the gravity aspect, are minor at best. It’s really that gravity delay that accentuates the small differences to give a pretty stark impression. Birth by Sleep and Dream Drop Distance are so far afield of the gamefeel of the main series games that it’s clear there was no intention of recreating those mobile games for KH3’s release. The developers have further made it clear their intention to deliver an experience their longtime fans can enjoy with the changes made to the Remind DLC.

In fairness, it had been 13 years since a main Kingdom Hearts game had been made when KH3 was released in 2019. With just a few tweaks I feel they were able to bring it up to parity with KH and KH2 in terms of fluidity. It’s not the tightly wound, exceptionally blisteringly fast experience of KH2 precisely, but do remember that KH2 was developed only three years after the original, so the developers were coming right off the back of designing an already exceptional combat system. The experience was fresh. From where I stand I don’t think the future of KH is in any danger. Three years on from KH3 as of the time of writing this in 2022, and KH4 seems to be around the corner, poised to improve in ways reminiscent of how KH2 improved.

The Kingdom Hearts 4 reveal trailer doesn’t actually show any basic attacking in favor of mostly displaying the new movement options, and any gameplay it does showcase is subject to a lot of change to begin with, but what it does show looks pretty snappy and responsive to me. I’ll let you be the judge. The KH team learns quickly, and their intentions for this series’ gameplay have been made clear vis a vis the Remind DLC update. They understand the data I’ve so painstakingly gone to lengths to describe and how it affects gameplay, clearly. The KH3 update was so precision built for improvement it’s kind of astonishing. And, with KH4’s refocus on ‘reality’ as an aesthetic, I would not be surprised if a little more gravity came back to the party to polish the combat system even further into something really special.

Whatever you’re talking about, I don’t care…