Got Splatoon on the brain, so that’s what I’m gonna talk about today. The game’s preeminent horde mode, added in Splatoon 2, and expanded in Splatoon 3, to be specific, Salmon Run. So essentially I adore Salmon Run, it’s some of the most fun I’ve had with a horde mode in a game, that is, a mode in which waves of enemies hound a team of players in hordes, as the players are tasked with holding them off. In Salmon Run, four plucky young squidkids and octoteens are on the clock to collect golden salmon eggs for their employer. Each run is divided into three waves of increasing difficulty, which can take a number of different forms at random. During each wave, hordes of minor salmonids of a small, medium, and large variety will hound the players, and occasionally larger ‘boss salmonids’ will appear. They are more dangerous and harder to take down, but each drop a number of golden salmon eggs, which then must be carried, one at a time per player, back to a centrally located basket to meet each wave’s quota of golden eggs. Fulfill that goal, and you progress to the next wave. I’m going to go over my perspective on the various elements that make Salmon Run work so damn well. It starts with the maps the game mode takes place on.

A Space Where Moments Happen

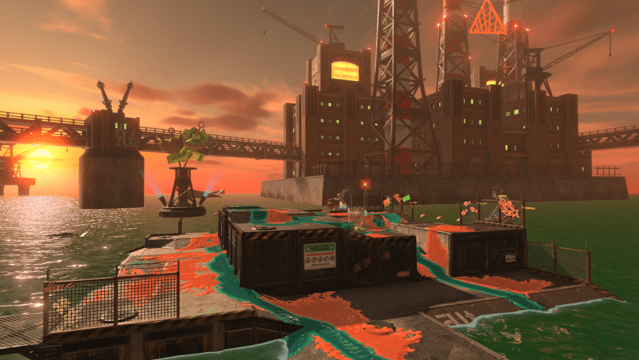

Salmon Run maps seem pretty simple on the surface. Smaller than Splatoon‘s versus maps, and usually approximately circle or square shaped. They all hold a few interesting features in common, though. For one, they all feature a large amount of elevation variation. This is important, as most salmonid cannot directly climb walls like players can, and thus will have to path around and through the level’s various ground passages. That’s important too, those passages. The heavily varied elevations create a lot of corridors and enclosed spaces. These enclosed spaces can lead to players getting trapped with enemies, in dangerous situations. That’s the point, Salmon Run maps tend to be less open to facilitate this up-close encounters, to really engage the players with how their enemies move and operate. Strategy becomes essential to keep yourself from being cornered. All this creates exciting ‘Moments’ of high action, that keep Salmon Run interesting.

Speaking of being cornered. Ever notice how all the Salmon Run maps are similarly shaped? Specifically I mean, if we are to assume they are basically the shape of a square, then three of their ‘sides’ are always exposed to the water, where salmonid always spawn from. The fourth side, is not.

This will cause salmonid, again always approaching from the beachheads, to surround players as they navigate, but never directly from behind, as that would feel unfair. So the minor salmonids; tiny small fry, player-sized chums, and larger imposing cohawks, all walk toward players at a moderate speed, usually in lines and clumps, then try to melee attack. The damage dealt by each, and the damage each can incur before being dispatched is proportional to their size. It might be one’s inclination to largely ignore the unruly masses and focus solely on bosses, but this would be a mistake, especially as that aforementioned difficulty scale begins to skyrocket. There is one wall for players to back up against in the face of the coming forces, but they also must keep an eye out for flankers, constantly. peripheral attention becomes essential. Reacting for flanks is another of these exciting ‘Moments’. Waves of high danger follow waves of control, forming Salmon Run’s interest curve.

Game is Hard

So one thing that a cooperative experience like Salmon Run needs is longevity – something for players to latch onto so they keep coming back. One way Salmon Run achieves this is through an adaptive difficulty system. Based on how frequently a player is winning at Salmon Run, an invisible difficulty scale will begin to go up for them. Higher difficulty scales mean more frequent salmon spawns, and higher egg quotas. The higher scales demand more and more efficiency of the players.

So, cleverly, Salmon Run starts out very forgiving, allowing players of any skill level to begin to succeed and claim their rewards for the game mode. What I find commendable is how unrestrained the upper echelons of this scale is. A lot of the fun of horde mode comes from the horde- tons and tons of enemies coming at you all at once. Through grit and determination, you can overcome.

Salmon Run also includes a lot of wrinkles and surprises, such as the special event waves, where the rules of the game are tweaked slightly. For example, high tide might shrink the play area, making the next round very claustrophobic. What is all this for, then? Well, like the level design which emphasizes situation awareness, every aspect of Salmon Run from its maps, to its enemies and bosses reinforces specific fundamental skills in the Splatoon player’s toolkit. Players are randomly assigned weapons they are forced to use, reinforcing general adaptability and understanding of the game’s mechanics. The maps are laid out to reinforce situational awareness and navigation skills. Specific bosses reinforce specific weapon-handing skills. As the game’s difficulty ramps up, so does the speed of the game, and the skills needed for mastery are further and more rapidly drilled into the player.

Entity Cramming

“Entity Cramming” is a term originating from Minecraft, a game which allows a very large number of entities like players, enemies, and animals to coexist in a very small space. Salmon Runs can get very cramped, very fast. Especially at higher difficulties with very high spawn rates, or during high tide, at which the viable play space shrinks. There is a need to combat the problem of overpopulation in a small space, to keep the game running smoothly and feeling fair. A lot of salmonid bosses possess some way to impede player movements or player attacks, or both. Even beyond that, with too many enemies present, it would become unfeasible for four meager squids to fight back, which would create an overwhelming and unfair disadvantage for the minor mistake of acting just a little too slow or inefficiently. There’s also the random chance that bosses might occupy the same relative space.

To combat this, salmonid bosses represent an inherent risk-reward factor. With many of them bunched up, there is great risk to approach them, but many slamonid bosses represent an opportunity to clear wide swathes of salmon all at once. There are bomb salmonid, for example, which explode and deal damage to their allies when defeated. When enemies are bunched up, players with wide-reaching area-affecting weapons can take out multiple of them at once. All bosses explode into friendly ink, which is toxic to some salmonid. The new Slammin’ Lid boss, added in Splatoon 3, will utterly crush any salmonid beneath it, bosses included, if it is goaded to use its slam attack.

So with this built-in risk-reward for salmonid bosses, it’s never too daunting when they team up. With a clever and careful approach, bosses can be used as weapons to take out other bosses! So while difficulty scaling leads to huge hordes of enemies, it also creates this rubber-banding effect where huge hordes of enemies can actual mean an increase in overall efficiency, where you’re dispatching two or three bosses at once, along with their smaller minions, rather than just one. At high levels of play, golden egg collection can skyrocket to huge profits.

Teamwork Teamwork Teamwork!

The real key to excelling at Salmon Run is efficiency, and efficiency is teamwork. It is virtually impossible to accomplish some of this game mode’s higher-end challenges without utter mastery and knowledge of your role on the team. The randomly assigned weapons ensure each player accels and struggles with some specific task. Long ranged precision weapons can take out unshield bosses from a distance with ease. Heavier wide-area weapons can dispatch crowds of small salmonid *much* faster that snipers can. Some weapons can defeat salmon from safety whereas others have to get up close and personal.

Later on efficiency becomes to important, that if you are ever swimming around with a full tank of ink ammunition, you are kind of a liability. My advice to ace Salmon Run? Always be doing something, whether its clearing small enemies or ferrying eggs. Rescue teammates as quickly as possible – four sets of hands outperform two or three. Everyone has a role to fill, even if that role is just moving eggs around, because you’re weapon is ill-suited to the current event wave. In Splatoon 3, a new event wave called the Tornado was implemented to highlight this. Large quantities of eggs spawn far away from the basket, so the four players must form an assembly line of sorts to taxi them across enemy territory. Kind of reflects the rough work environments that the game uses as its horde mode backdrop, huh? In fact, there’s a lot of parallels to game development in general..

The Main Event: The Bosses

The bosses in Salmon Run are fun, inventive, visually creative, goofy, funny, and irresistibly compelling. They all fill specialized niches in the gameplay, and each reinforce a skill for the player. They all have specific rules for how best to deal with them. There’s a lot, so I’m going to rapid-fire-style review them in a series of mini boss breakdowns and see how they fit into this scheme, with a little more detail given on the new bosses added to Splatoon 3‘s Salmon Run.

Steelheads are giant salmon with bombs in their heads. They arm the bombs for a moment, then throw them as a player approaches. They teach precision aiming, as their weak point bobs about while it’s vulnerable. They also reinforce reactiveness to bombs and ground hazards – a common danger in Splatoon.

Steel Eels demand the skill of tracking moving targets, their weak point constantly on the move, and occasionally blocked by their own shield-like bodies. Terrain navigation is crucial here too, as getting sandwiched by one against another enemy or wall means death.

Scrappers, or Jalopies, as I like to call them, teach the skill of flanking. They always turn to face attacking players, and they are shielded from the front. Using teamwork, one player can distract or stun from the front as they other takes them out. This is one of the ‘kiteable’ bosses, which can be lured by the player to be very close to the basket when they die, leaving eggs right there. Retrieving golden eggs past salmonid enemy lines

Stingers are of a class of salmonid bosses I call ‘globals’, as they can damage players from anywhere on the map. Stingers use a long-range beam unimpeded by terrain. Stingers teach players a hierarchy of needs for the game. It’s near-impossible to kill every enemy as they spawn. Just reaching your egg quota and surviving is paramount. You have to triage your attention to what’s most important. Stingers are important. You’re excelling when you put out fires before they happen, and addressing Stingers quickly is a good example.

Maws can also be kited to the basket for easy eggs. They teach how to swim away while placing a bomb, which generally kills them. A surprisingly practical skill, as bombs cost a lot of ink, but swimming replenishes it. Efficient!

Drizzlers are a global salmon which create damaging rain that also ruins friendly turf. They teach lining up shots, and maintaining relative positions between player and enemy, as they are most easily dispatched by deflecting their projectile back at them. Lining this up is strict, to aim well!

Flyfish. Ooooh Flyfish. Perhaps most infamous of all salmonid. They are hovering mobile missile vehicles which periodically fire squid-seeking missiles at players who must be moving to avoid them. This is global. They are easily one of the most dangerous bosses to keep alive, so a great marker of Salmon Run mastery has become one’s ability to safely and efficiently take them out. Taking them out quick is a true marker of friendship between allies. They teach precision use of the grenade sub-weapon, as you must land a grenade in its open missile launchers after it fires. Twice. Once for each launcher. It also teaches patience, and the truth of your own mortality.

The Slammin’ Lids (god I love that name) are one of two new Salmonid that seem to be purposed to teach one of the two new movement options in Splatoon 3. The lids are easiest to kill by baiting out their slam attack, then mounting them while they’re on the ground, to kill the pilot. The easiest way to do that, is by using the new Squid Roll, which allows rapid turning while swimming through ink. They are also one of the best example of the entity cramming solutions in Salmon Run, as I’d shown earlier. Their main threat is the impenetrable shield they produce beneath themselves, which can obscure lines of fire while they pump out small salmonid to shore up the enemy forces. They aren’t high-priority targets, but can become dangerous if they take up advantageous positions.

The Fish Stick is a toward carries by a rotating contingent of salmon. The stick is easily dispatched using the new Squid Surge, which allows one to rapidly ascend a vertical surface. The Fish Stick fills a new niche in the game mode, which is the use of the player’s wall-scaling abilities, and introduces an enemy that is itself terrain that can be inked. What’s really interesting is that the Fish Stick’s terrain remains in play even after it’s defeated and its eggs are retrieved, opening new strategic options for players. This can be a double edges stick though, as while the extreme vantage is usually safe, some salmon like the maws or dreaded fly fish can use its small surface area to trap players.

The Flip Flapper is a salmon dressed like a dolphin which drops rings of enemy ink where it is about to dive. Filling in this ink with friendly colors before it lands, stuns it and renders it vulnerable. I love this thing because it teaches the teamwork of efficient ink coverage. Nothing worse than teammates who waste time inking something you’ve already inked. Working together, these dolphin wannabes are no challenge, but they also serve Entity Cramming well, as they are very weak to the splatter from other enemies nearby being killed.

Big Shots are tough guys with lots of health that stay on the sidelines. I think what these guys are meant to teach is how the AI operates and reacts to player movement. You see, the Big Shot is a global who uses a machine at the beach to launch wave-generating projectiles toward the basket. Very inconvenient. What is, convenient, though is that the player can use the same device to launch golden eggs toward the basket. Toward, not in, mind you. Another player still has to be there to cash the eggs. If they don’t, salmonid will come in and snatch them up, making the players’ efforts a waste of time. What’s more, is that spending too much time on the beach, which I might remind you is where salmonid come from, can mean quickly becoming overrun by enemies, and trapping you in a place which is very dangerous and inconvenient to reach. Teaches teamwork and restraint.

There are a few more event-specific bosses, but that was a lot, I think, so we’ll leave it at that.

EMERGENCY!

JUST KIDDING! They couldn’t have a sequel without upping the ante a little, right. At (slight) random, after winning a few Salmon Runs, the new King Salmonid Cohozuna will appear. You have a mere 100 seconds to send him back to the briny deep in order to secure the special fish scale rewards he provides. Really, there isn’t much to him or his AI beyond standing as a suitable final challenge to really test the player’s mastery over all these bosses and systems. His implementation is pretty clever, though.

He has a LOT of health, so normal weapons will simply not do enough damage to vanquish him on their own, not in the time allotted. To beat him, you’ll have to leverage golden eggs, which can, in this bonus boss round, be thrown with zero ammunition cost. They deal massive damage to him, and the only way to get them remains the same: defeat the boss salmonid that accompany him. You’ve only got 100 seconds, your team, one special weapon, and the ink your back, so I hope you’ve been practicing your aim and reaction time.

He seems to prefer to follow the last player who damaged him, so he can be tanked somewhat. He’s not that dangerous on his own. He’s slow, and only has two real attacks. One where he belly flops right in front of him – so keep somewhat at a distance. His other is a jump, which does heavy damage where he lands. Be ready to move. Other than that, it’s his health and his bulk that is the challenge. The team needs to work together to get enough eggs to bring him down, while positioning him such that he is not a threat to the team, and such that he is not covering vital resources with his body. It’s a stiff challenge, but if you really push your self and put a full understanding of all the little things Salmon Run has been teaching you, it’s very doable. A suitable finale to any work day.

The Cohonclusion

Where. That felt like a gauntlet. We all get through okay? Yeah so I love Salmon Run, to reiterate. It’s got so many little clever design considerations to acutely tune the experience and promote active thinking while playing. Sure, it’s great fun to goof around in with friends, but even at a casual level, enough exposure to the game mode will gradually train certain behaviors that make you better at it. I think that’s a sign of some absolutely excellent game design, that deep consideration of incentives and how minor tweaks to Splatoon‘s gameplay setup will reinforce certain behaviors. Salmon Run is also just where some of Splatoon‘s considerable creativity comes to the fore. I mean “Slammin’ Lid”? An eel made of shower heads that forms an impenetrable wall of showering ink? A mothership that is a warehouse container full of smaller crates that deploy salmon? Come on. This stuff is gold.

DO YOUR JOB!