I love parrying things in video games. You might have already guessed that. I’m always looking for how and why things work or don’t work in games, so I have a particular interest in one of my favorite gameplay mechanics, the parry. So what is a parry? In the context of an action game, I’d define it as a maneuver the player can execute on the fly to nullify incoming damage and disarm enemy defenses, which requires an acute execution of timing to succeed. Commonly, it’s a button press that initiates a short window of animation during which, if an enemy attack connects with the player character, the parry activates. After considering how to approach the design of this gameplay mechanic, I’ve decided there are three pillars of a good parry mechanic: usability, versatility, and impact.

Usability describes the practicality, from the player’s perspective, of actually using the parry at all. How restrictively difficult is the timing necessary to succeed in using one? Is the risk of using the parry worth the reward? How necessary is the use of this parry to succeeding within the game? Are there other specific considerations like spacing that make the parry more or less practical?

Versatility describes the frequency of general use cases for the parry. Can the parry be used to deflect any attack encountered in the game, or is it limited in some way? Can even large and powerful enemies be parried? Do you need a specific weapon or in-game skill to use the parry? Is the parry’s reward worth forgoing a more straightforwardly offensive approach?

Impact is at the center of what makes me want to use a parry. A parry can be powerful, but ultimately I am motivated to use it by how fun it is. What’s the audio-visual feedback of a successful parry like? Do I get a rush from disarming my opponent, or is the reward for parrying barely noticeable? Does it make me feel powerful? Does it make me feel skilled?

FromSoftware or FromSoft is a Japanese game developer well known for their popular action games, all of which in recent memory include a parry of some kind. I want to run through three of their flagship titles, the original Dark Souls, Bloodborne, and Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice, and analyze their respective parry mechanics through this lens I’ve come up with to see how it can be applied to specific cases.

The parry mechanic in Dark Souls is an interesting beast. A favorite of the game’s more hardcore fans but, in my experience, one that new and even many veteran players ignore completely. It’s powerful, and it’s fun to use once you get the hang of it, but that’s kind of the problem, it’s not very fun to learn to use, and many players will not bother with it, as it is far from essential to completing the game. I’ve found most friends I’ve introduced to the game simply ignore the utility of parrying, or try it once and discard it in favor of the game’s more developed mechanics.

The parry in Dark Souls suffers severely from a lack of usability and versatility. Usability, as I explained, is my concept of how practical it is for a player to actually execute your parry maneuver consistently and successfully. Firstly, this parry is not universally available – the player must be wielding a small or medium sized shield in their off-hand. Given the wide and varied options of character customization in this game, it’s possible a player won’t be using a shield at all. I think the greatest source of dissuasion for using this mechanic, though, is how difficult it is to succeed with it. Dark Souls has a very specific and narrow window of time at which a parry will succeed. An enemy’s attack must connect with the player character during this 6 frame window – that’s one fifth of a second. Needless to say, it is a difficult mark to hit. Now, with practice one can hone in on Dark Souls‘ very consistent and reproducible rhythm. Not every enemy attacks with the same timing, but they all share a fairly general pattern of wind-up, swing, and follow-through. Once you get it, you’ll find parrying a pretty consistent tool.

However, the skill floor to reaching this point of consistency is restrictive, even by this game’s standards. Given how great the risk is of failing a parry in this game, and how the game itself trains players to be extremely risk-averse with enemies that deal massive amounts of damage when interrupting player actions, players are naturally disinclined to even take those risks. Thus, they’ll not learn the parry timing. What’s more, most enemies can be thoroughly dispatched, with far lesser risk, by simply striking them down with your favorite weapon or spell when the foe’s defenses are down, between their attacks. I conclude that the parry in Dark Souls is not entirely practical, or usable without a great deal of personal investment, time, and effort most players will find better spent in learning the nuances of movement, dodging, and attacking. These options are far more practical, realistically, even if the parry becomes very powerful once one masters it.

This would be enough turn off most players from the mechanic on its own, but the move also struggles in the versatility department, meaning the frequency of its general use cases. Dark Souls is filled with enemies that can be parried – essentially any enemy that can suffer a backstab. I’d always say that any enemy with an obvious spine that your player character can reach can probably be backstabbed and parried, as a general rule of thumb. Not every enemy matches this criteria though, and nearly none of the game’s 25 boss encounters do either. Boss encounters are a major part of this game, and something players will be spending a lot of time on. They’re also notoriously among the game’s most difficult and high-intensity segments. Since parrying is useless in those encounters, it further disincentivizes paying the mechanic any time or energy. If you can’t use a move for a game’s greatest challenges, what worth is it? Any real world skill building towards parry mastery is, objectively, better spent on other things, if finishing the game is your goal.

I like using the Dark Souls parry – it’s got excellent impact. A harrowing low boom sound effect accompanies its successful use. Parried enemies reel in a wide, exaggerated swooping animation, soon to be followed by a riposte that drives a weapon straight through them, gushing comical amounts of blood (if the foe has blood). It all really accentuates the player’s power and superior skill over the opponent. The totality of the audio-visual feedback here is excellent, it’s just a shame so few will ever get to actually see it. The move is simply not useful to a significant portion of the player base.

When a mechanic like this goes so underutilized by your players, the designer might ask themselves what’s causing this discrepancy, and what can be done to address it.

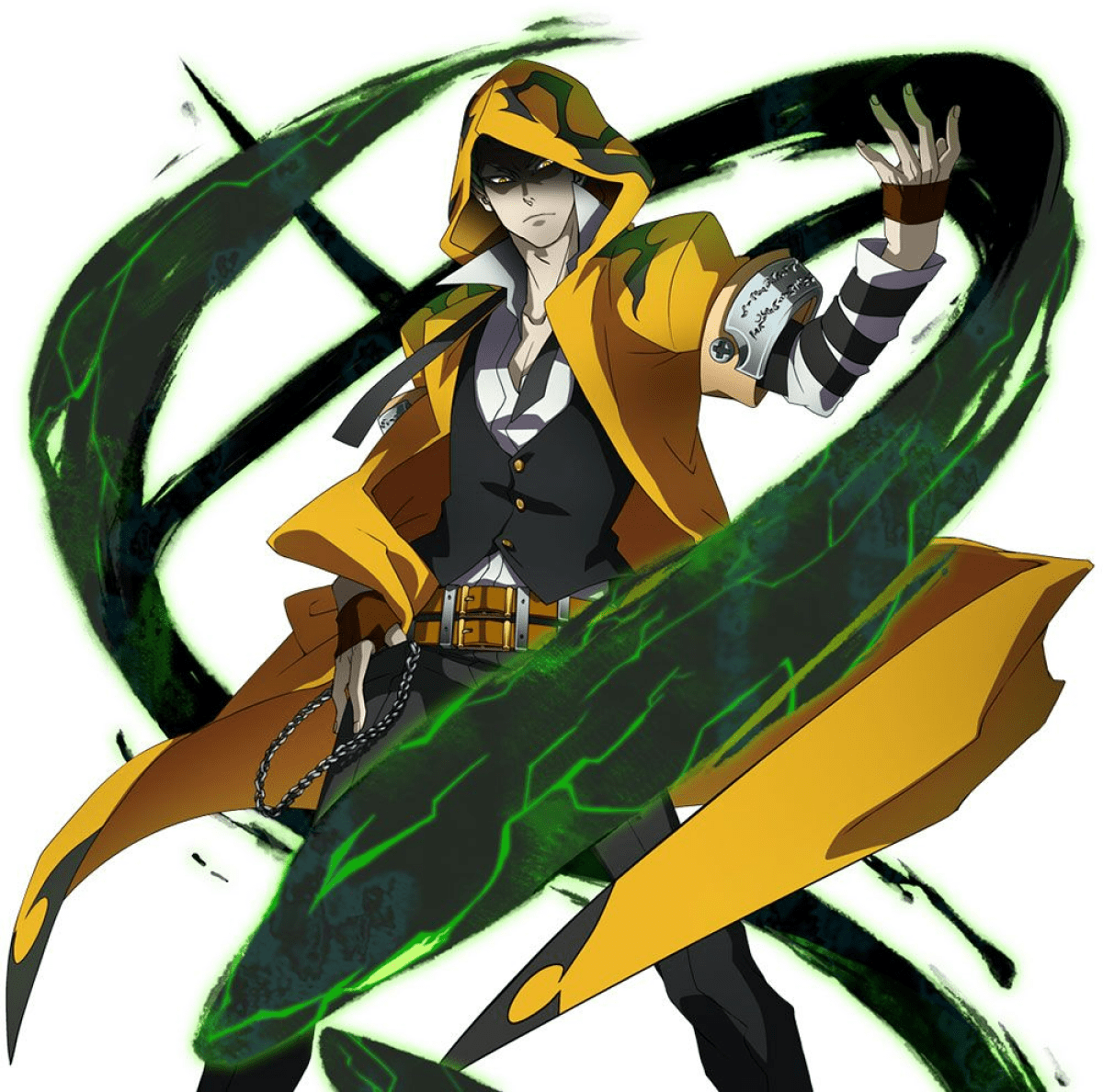

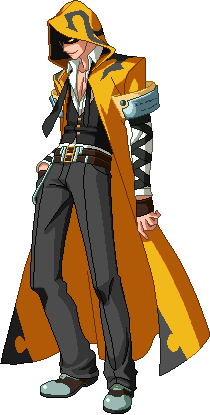

In Bloodborne, FromSoft wanted to shift to a more action-oriented system, less about patient and considered movements, more about reaction and aggression, as compared to Dark Souls‘ more traditional RPG inspired roots. As part of this shift, the parry in Bloodborne was made to be more of a central mechanic than in Dark Souls, something to be expected of the player regularly throughout combat encounters. So that means getting players to actually use it. First, FromSoft needed to address usability. Bloodborne‘s parry is unique in that it takes the form of a projectile. This accomplishes two things. One, it makes accounting for space exceedingly easy for players. Dark Souls was fairly strict about where player and opponent were standing for a parry to successfully work. In Bloodborne, if an enemy is shot during the tail end of its attack animation, it will be parried, no matter its distance from the player. Two, this means the player does not have to put themselves in direct danger to parry, as an enemy can be parried even if their attack is very unlikely to actually hit the player. The risk to parrying now feels much more proportional to the benefit, making it a valid alternative to just wildly attacking.

As the timing for Bloodborne‘s parry is now timed to the enemy‘s attack, and a moving projectile, rather than lining up the player’s parry animation with the enemy’s animation, the player really only has to track one movement, the enemy’s. Together, these elements remove a ton of cognitive blocks on actually using Bloodborne‘s parry system, so its usability is extremely effective by comparison. Bloodborne‘s parry is also extremely versatile. When looking at the 30 or so bosses in the game, about 15 of them can be parried, roughly half, making mastery of the parry a far more effective tool in way more situations than it was in Dark Souls. Bloodborne doesn’t shirk in the impact department either. The same familiar boom sound effect accompanies a success, and can be followed up with a violent and beastly visceral attack that grabs the enemy’s insides, twists them, and rips out a huge gush of blood, knocking the foe to the ground and stumbling nearby enemies. The player hunter’s sense of superiority over their prey is the focus.

The Dark Souls parry had another issue I didn’t mention; if you did master it, and made it a consistent tool in your arsenal, many enemies outside of boss encounters become exceedingly easy to deal with, even if they are still fun to beat. Nevertheless, this runs the risk of the move becoming too powerful, especially if it’s easier to use. FromSoft’s solution to this was to make parry attempts a limited resources. This elegantly maintains the risk of attempting a parry, while assuaging the frustration of losing one’s own progress as a result of said risk. There’s still some risk of injury to a failed parry, but it’s much less likely than in previous games, most of the risk is the parry-centric resource of quicksilver bullets.

If Bloodborne made parrying a more central mechanic, then Sekiro made parrying a core mechanic, one of the primary action verbs of the game. Parrying is most of what you do in combat. Formally, the Sekiro move is called ‘deflection’.

To accomplish its design goals, Sekiro‘s parry is made to be even more accessible and low-risk than Bloodborne‘s. A deflection can be directly transitioned into from a block (which itself nullifies incoming damage), and a block can be transitioned to directly from a deflection. Both ‘block’ and ‘deflect’ are activated with the same button, block is simply the result of holding it. Deflections are initiated when the button is compressed, not when it is lifted, so erring on early deflections makes the maneuver even safer – deflections that fail for being used too soon simply result in a block. No damage is taken either way. The limiting resources of Bloodborne are gone here, at least for parries, so player’s will often find themselves using the deflection move even more than they attack, but this was the goal. Sekiro aims to evoke the back-and-forth clanging of cinematic sword fights, and the game is built around the interest of deflecting a series of attacks in quick succession. Any one given deflection is easy, but the difficulty can be smoothly ramped up by stringing a sequence of them together.

We’ve come a long way since Dark Souls, with a skill floor that is extremely approachable, without sacrificing the skill ceiling. Where the parry window of Dark Souls was only 6 frames, one fifth of a second, Sekiro‘s deflection window starts at the extremely generous, by comparison, half-second. This deflection window decays in size if the player abuses the deflect button. Deflecting rapidly and repeatedly causes the window to shrink down to only a small fraction of a second. The goal is to make any given deflection easy, but the player is encouraged to use their own powers of reaction and prediction, rather than relying on spamming the button. Even still, this window decay is also generous, as the deflection’s full capability is restored after only a half second of not using it.

All this to say, Sekiro has extremely generous usability for its deflection mechanic. It has to, as deflection is the primary tool for defeating enemies in this game. Were it as restrictive as the parry in Dark Souls or even Bloodborne, it would be an exercise in frustration. To counterbalance this, the individual reward for one Sekiro deflection is much lesser, and you need to do a lot of deflections to add up to a bigger reward.

Sekiro is a masterclass in parry versatility. The deflection maneuver is applicable to nearly every encounter in the game. It’s extremely generally useful, so much so that exceptions, attacks which cannot be deflected, are unlikely to be deflected, or require other special maneuvers to deflect, are given their own glowing red UI graphic to further make them stand out. Outside of that, if it deals damage, it can be deflected by the player’s sword, near-universally. Formalizing what can and can’t be parried in this way is also helpful for usability, as it removes guesswork on the part of the player.

When deflecting successfully, right orange sparks fly like a firework cracker was set off as a cacophony of metal sounds clang in satisfying unison. The audio-visual feedback for a successful deflection is actually kind of subtle, compared to simply blocking. It is merely a heightened, more intense version of the block visuals, just distinct enough to unambiguously be its own separate function to ensure players know when they’re succeeding, but similar enough to not be distracting. This makes sense, as players are expected to deflect a lot of attacks in any given encounter. A series of successful deflections looks and sounds like a larger-than-life battle of master swordsmen, with sparks showering about amidst the metal clanging. When an enemy has finally been deflected past the limits of their endurance, Sekiro will delight players with some of the most lavishly animated executions in video games, anything from the tried and true gut-stab, to decapitating a gorilla with a hatchet the size of a refrigerator, to gingerly extracting tears from a dragon’s occular injury. The impact of Sekiro‘s parry system is not only good, but usually proportional to each situation, even though the overall impact of any one given deflection is not super intense.

It’s clear somebody at FromSoftware loves parrying things almost as much as I do. It’s a common mechanic for a reason, giving players an area of skill to strive for mastery over, which reinforces a sense of power. Few things can make a player feel more powerful than successfully turning enemy attacks against them. Over the course of these three games, FromSoft has made parrying more and more central to the experience, to the point of it becoming the main point of focus for Sekiro. It’s clear there was an awareness of how neglected parrying was in Dark Souls among casual players, and even some veterans. They needed to find ways to make using it more attractive, without sacrificing the sense of power it imparted, the thing that makes it fun in the first place. While the Dark Souls parry has its flaws, I’m glade they persisted in iterating on it. I think Sekiro and bloodborne have two of the most consistently fun combat systems out there, and the excellence of their respective parry mechanics are a huge part of that, in Sekiro especially, which deserves its own write-up, eventually. The metrics I’ve come up with here to assess parry mechanics are just the way I look at things, though. It’s useful to look at design through a variety of lenses. So the next time you stab some zombie in the face after battering its arm away like you’re in a kung-fu movie, think about why and how that maneuver works the way it does.

Hesitation is Defeat…