Persona 3 is being remade and they’re changing some things about how dungeon exploration works. I presume it’s going to look a lot more similar to how Persona 5 and Persona 4 does things. In my last playthrough of Persona 5: Royal I was struck by a thought regarding how its various systems fit together. I wanted to get it down in writing.

It has been oft refrained that modern Persona combines the appeals of two very different modes of play. This is true to an extent, but a zoomed-out bird’s eye view of the actual decision-making structures of play in the modern Persona series reveals that the differences aren’t as pronounced as you might think on a high level. Ultimately, the entirety of Persona‘s interactive gameplay is a series of resource management decisions.

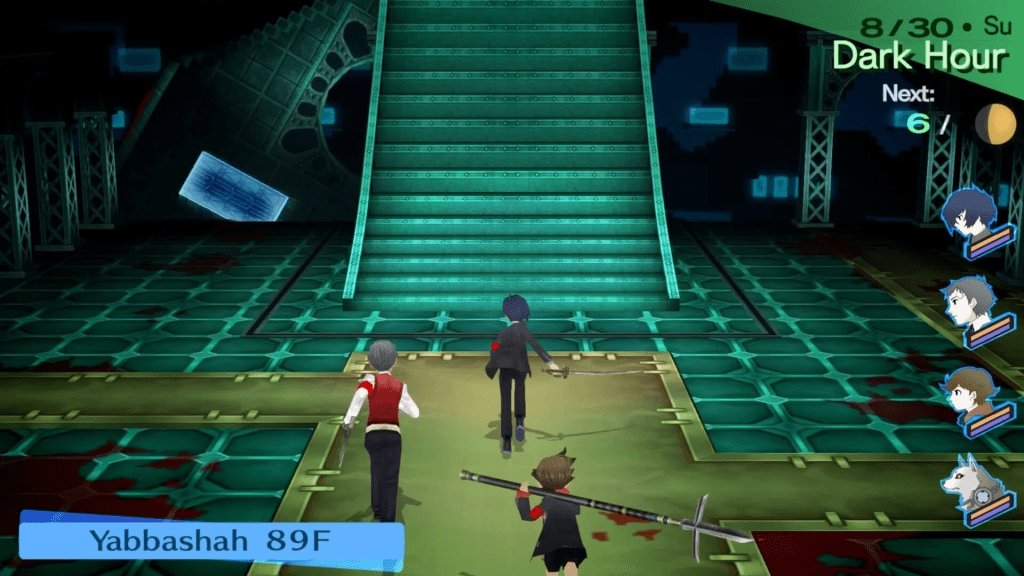

Man, this is going to look so much better in HD.

There’s this concept I like to come back to when thinking about games designed with distinct modes of play such as this. I think it is generally a good idea to look to forming come kind of parity between different modes in a game, even if they’re technically different. For example, the mid-2000s were in love with turret sections. If you know, you know. I always felt like these fit most elegantly in with games that are already about shooting. Firing a stationary gun from a first person perspective *is* a different mode of play than running and gunning in a game like Ratchet and Clank. However, the game is about aiming and shooting big guns to begin with. So even though the rules are little different, the player can more intuitively slide into this different mode of play without it feeling jarring. On the other hand, players may find the addition of the all-too-common fictional card game within the game off-putting because of how different a card-game mindset is to, like, a platformer. Intelligently, most games with card-game minigames keep them as optional side-content.

The main item that unifies all of the game’s various systems is time. When interactive mechanics form a cohesive system, gameplay decisions exist in a hierarchy. Where and how you use your in-game time sits at the top. Persona models the daily life of a sociable high schooler and how the player chooses to use each day is a decision that cascades down across all other systems. Persona breaks down into two primary gameplay modes: the social simulator, and the strategic turn-based combat dungeon crawler. Ultimately though, whether you choose to spend time getting ramen with classmates, working out at the gym, studying for class, or fighting horrific hell-beasts in humanity’s collective unconscious, you’ll be spending a day of in-game time for each instance of each task. Days are a finite resource, and how you choose to spend them is the primary mode of interaction in Persona at a high level.

Time ticks down on your game, just as it does on the summer of your youth.

Persona’s dungeons are bursting with tough encounters with monster designed to whittle away your resources; health, and spirit power, or SP. These are long gauntlets meant to stretch your abilities to endure numerous combats to the breaking point. There is no reliable method to restore SP within these dungeons themselves. The only way to restore your combat resources fully is by ending a given dungeon session, and allowing time to pass to the following day. That means, of course, that you must spend at minimum one additional day of in-game time to complete the dungeon. This limitation of SP restoration is crucial, as it forms a limiting reagent to dungeon activity. It is possible to complete any dungeon in a single day, but only with extremely deft management of SP. This one resource’s scarcity creates a space where skilled play can lead to greater reward, without the implied penalty of inefficient play being too punishing. Losing one day is not a big deal. Wasting a lot of days though, adds up. Failing to manage your combat resources efficiently leads to an inefficient use of your social resources.

It’s this inter-relation that forms the bedrock of the gameplay loop in Persona. You have a limited number of days to complete a dungeon. And beyond that, you have a larger, but still limited number of days before the entire game concludes. Therefor, it is implicitly more desirable to complete dungeons in a timely manner, leaving more in-game days free for the player’s other social projects – fostering relationships, improving one’s social skills, earning money in a part-time job, etc. The latter of which can be intrinsically motivating through appealing character writing that makes the player want to engage in this social simulation. The social sim half of the game forms an extremely important part of this gameplay loop bedrock, but it’s important to note it would be not so nearly engaging without strong narrative context Persona puts forth for the social aspects of its gameplay.

Many choices, but which- it’s Chie. You should pick Chie. Hang out with Chie.

You need to complete each dungeon in a timely manner, so you need to get stronger. Normally, in an RPG, you mostly do this by just fighting. Defeating more monsters means leveling up, means increasing your player characters’ power. This is also the case in Persona, although it is intentionally a lot more limited. When your protagonist levels up, his maximum HP increases, and his maximum SP increases, but that’s about it. His damage doesn’t go up, his defenses don’t go up, etc. It’s a good thing, then, that leveling him up does offer one other benefit – it increases the level of the titular personas that you can create, which, if you didn’t know, are reflections of the inner self that can be summoned to do battle. For our purposes and for the purposes of strictly talking about gameplay mechanics, they are basically pokemon. These personas determine the protagonist’s stats.

The developers do a couple of very clever things in how they handle power progression for personas. Personas themselves can level up, and their stats will increase accordingly, however, there is an effective soft cap to their usefulness. After a few level ups, you’ll notice your persona’s power growth start to kind of bottom out, as they become increasingly more difficult to level up, the acquisition of new abilities becomes scarce, and their old abilities just don’t quite measure up to the stronger monsters you’re fighting. This is the game’s way of always encouraging the player to make new personas as they level up. Each persona is not a lifelong companion, but rather, basically, a stepping stone to ever greater things. This behavior is further encouraged by an experience bonus a persona received upon being fused. This bonus can be massive and is a much more efficient use of your time than leveling up a persona in battle. How do you get this bonus? That’s right, the social sim gameplay mode.

The persona fusion animations can get rather fanciful. I went bowling with my cousin and I am now more proficient at decapitation.

Each persona has a type associated with an arcana of the tarot deck, and each of those arcana is associated with one NPC the player is encouraged through narrative context to form a relationship with. The rub is, once again, you have limited days with which to foster such relationships. So what type of personas you empower, and how efficiently you do so, is entirely up to you. Because there’s a lot of strategic skill involved in the social aspect of these games. Provided you are not simply following an online instruction guide, the social game of Persona involves a lot of forethought, planning, understanding the schedules and exceptions to the schedules of NPCs, how long certain long-term projects like improving your academic stats will take, how all this intersects, and how to balance it all.

Here you see persona 3’s lovely arcana artwork, I guess in case you’ve never seen a tarot deck before.

This is, of course, a sort of tongue-in-cheek rumination on the nature of social interaction in real life – how easy it is to foster so many entanglements and commitments that it becomes a game in and of itself to manage them all, but also very compelling gameplay, that some players may not even notice they’re partaking in. The metaphor here is clear in narrative as well; friendships make the heart grow stronger, and your weapons are personas – the power of the heart. You delve into the game’s respective dungeons, and engage in strategically engaging combat one day, then decide whether your time is better spent hanging out with that girl you like, or patching things up with your friend whom you had a spat with the other day. Because even for how difficult it can be, it’s all worth it – just like forming bonds in real life – through the intrinsic narrative reward of getting to know these characters to the extrinsic gameplay reward of increased power in the dungeon, meaning you can complete the dungeon faster, meaning you have more time to play the social game, meaning you grow even stronger. And thus, the gameplay loop.

There are a lot of numbers and words to look at here, but it’s all in service of maintaining that loop.

Persona‘s combat, similar to its sister series Shin Megami Tensei, is itself primarily a resource management game. As a turn-based RPG units of action are divided into discreet units. The player takes action, then the enemy monster does, etc. Your SP or HP can be spent on more powerful attacks, but can also be costly. However, if you don’t defeat enemies quickly, you may take damage which will require the expenditure of SP or healing items to recover. There are mechanics in place to extend the player’s turn to avoid this. However, utilizing this “Once More” mechanic most often involves the expenditure of SP. And even then, there are more and less efficient ways to spend SP, such as using a screen-wide attack to hit a group many enemies at the cost of significant SP, can be more efficient than using a single-target attack to hit each enemy in sequence. Understanding the balance can be key. Because both action and inaction can lead to loss of HP and SP, when fighting enemies in Persona, you’re really searching for the most efficient path to navigating each battle in terms of resources – weighing the potential losses versus gains in each given scenario, all in service of that ultimate higher level goal – clear the dungeon efficiently. This is the heart of Persona‘s combat system.

Exploiting weaknesses is one of the main ways to stay efficient in battle.

Each day, if you choose not to go dungeoneering, you must choose how the protagonist will spend their day. These units of action are divided into discreet days. The player takes action, then a day is expended, etc. Your time can be spent developing a bond with an NPC for those more powerful personas, but maxing out an NPC bond can be a costly long-term use of time. However, if you don’t get stronger personas, that can cost you in the form of excessive SP expenditure in the dungeons later. There are mechanics in play to make the development of bonds more efficient, such as seeing a movie with several friends – which buffs some social stat like charm, while also developing two bonds at once. Timing is crucial, however, because if one or both of the NPCs you bring to the movies is not ready to improve develop their bond, the act may do nothing for you. Understanding the balance can be key. You may also choose not to develop any bond, and simply spend the day working for pay to buy precious healing items, or weapons. Because both action and inaction can lead to loss of time, when developing bonds in Persona, you’re really searching for the most efficient path to navigating each day in terms of resources – weighing the potential losses versus gains in each given scenario, all in service of that ultimate higher level goal – clear the dungeon efficiently, so you can spend more time with your friends.

What we conclude from this, is that the social aspect of this game, when you really look objectively at just what mechanics are in play, is a turn-based resource-management game. Ah-HAH! I fooled you earlier, it turns out Persona‘s seemingly extremely different gameplay modes have almost exacting parity with each other! How about that. That’s right, I am making the case here that both of Persona‘s primary gameplay modes are essentially the same, when you get right down to it. It is the nuances of their execution and, crucially, their narrative context that is their distinguishing factor. The social mode is much more relaxed, with smooth music, good laughs, and little sense of tension or danger, outside the mundane stakes of going out on a date, or whatever. The dungeons and battles have very tense and exciting music, the narrative stakes are that if you lose you die, and you’re surrounded by nightmarish imagery. These contexts, along with the more immediate feedback of failure in battle vs. social situations, whose failure states are more nuanced, make dungeons a state of high excitement on an interest curve, vs. the social situations’ more mellow levels of excitement. With the two modes existing in a mutual loop, Persona quite naturally creates a very compelling interest curve.

Persona‘s themes, every Persona‘s themes have, at their core, the universal truth that true bonds with true friends make a person stronger. This is repeated a number of times in a number of ways in dialogue, but its also rather skillfully crafted into the very fabric of how the game systems inter-relate. The strong your bonds the strong you literally are in the game’s more dangerous situations. What really elevates it though I think, is how that desire to save the world with your buds further motivates engaging with them socially. There are a lot of games which began to ape Persona‘s ‘half combat, half social sim’ conceit following the breakout success of Persona 5. Some of them, though, I think miss the point here. Persona is not two separate systems that somehow fit together like magic, no. They are two very similar systems subtly distinguished in mechanics and narrative context to fit together seamlessly.

The ability to summon a Persona is the power to control one’s heart, and your heart is strengthened through bonds…