I try to play a lot of games. I find exposing oneself to a wide variety of ideas and precedent helps one form a better understanding of the craft. I especially am fond of tracing the development of certain ideas and precedents over long stretches of time. In a moment of hubris that could be perhaps, generously, described as “insane”, some friends and I decided to undergo the herculean task of playing through the entirety of the Final Fantasy canon. The Roman numeral numbered ones, anyway. There are scant few games with such a distinct and traceable lineage. This is but the first leg of a long journey. Perhaps by the end you dear reader, and I, will have learned… something.

…We’ll get there.

As this is a retrospective, expect at least some spoilers for these games.

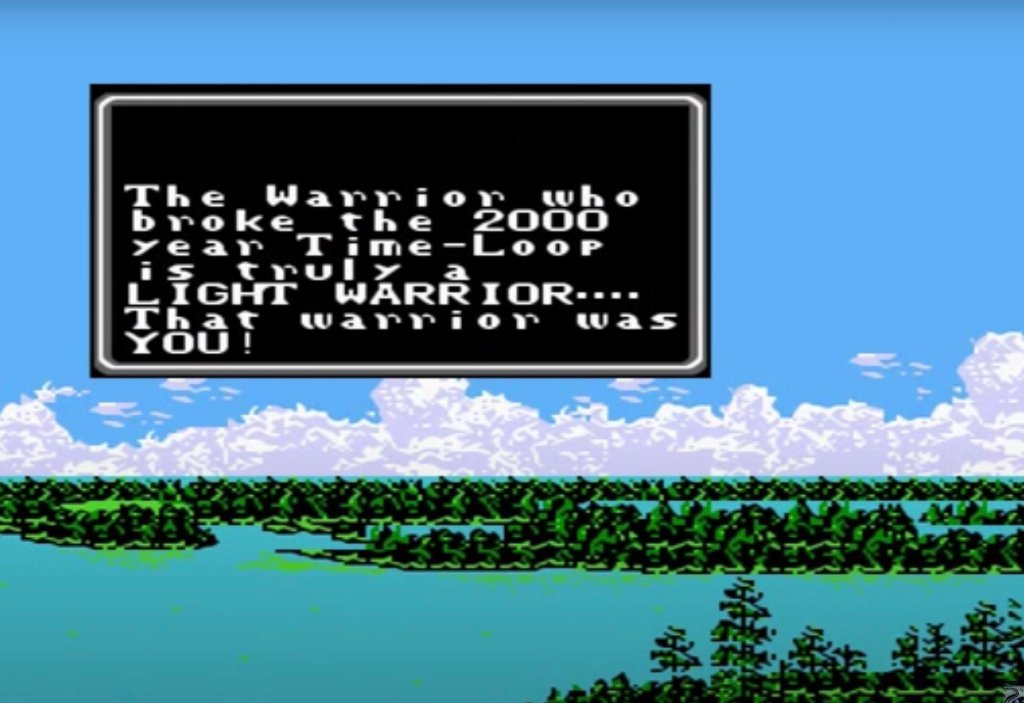

Final Fantasy I – Setting a Precedent

This is not going to be a narrative retrospective, at least not primarily, but story is an important part of this franchise’s identity, so I will touch on it briefly where I have something to comment about. Final Fantasy I‘s initial setup is about as simple as it gets. Four Warriors of Light set out on a quest to save a princess from an evil knight, then quickly discover they are heroes foretold in legend, destined to defeat Four Fiends, collect four magic crystals, and restore the balance of light and dark in the world. Still, even from humble beginnings, someone somewhere wanted to make this tale stand out a bit, with inspirations likely from Japanese mythology, manga, and anime, all of which tend to deal with rather esoteric concepts. The evil knight from the beginning of the game, Garland, reveals that he has enacted a complex time loop by sending the Four Fiends back in time. The result of this is that Garland becomes the immortal demon Chaos. Once defeated, all of our heroes’ adventures are undone, along with the evil of Chaos, though the memory of those adventures remains etched in the Warrior’s hearts. There are elements of Final Fantasy‘s heart here already. The esoterica, the high-minded fantasy concepts, the slight twinge of melancholy at the end of a long journey, all feelings that pervade the Final Fantasy games and their derivatives that I have played.

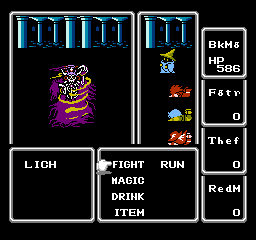

Yeah man, this guy…

At the outset, the player chooses a lineup of four heroes from a roster of possible character classes with different abilities. Notably, you can loadout your team any way you like. Use four white mages, aka healers if you so like. Use four glass cannon black mages. This level of customization sets a nice precedent going forward for what the gameplay of Final Fantasy is, I think. The game followed the release of Dragon Quest about a year earlier, and follows similar conventions of its contemporaries. Turn-based combat with simple rules, spells, attacks, and the ability to run from battle.

Often I judge my enjoyment of turn-based gameplay by how much leeway I am given for strategic thinking. There’s… not a whole lot of that in Final Fantasy I. Boss and enemy designs tend to be straightforward. One throws fire at you. One throws ice at you. Sometimes enemies are stronger than you, though, and figuring out how to maximize your heroes’ damage while keeping them alive can be a bit of an entertaining problem.

The game’s visuals are simplistic, but refreshingly uncluttered.

My friends and I did arrive at a rather interesting strategy. It’s pretty apparent that it wasn’t the primary method of play, that it was a strategy unique to us, so that’s pretty cool. We had a part of one strong physical attacker, the warrior, one potent offensive mage, the black mage, one healing support, the white mage, and one jack-of-all-trades red mage. Our go-to method is thus: The white mage casts a strength-enhancing spell on our warrior, and the red mage casts a speed-enhancing speed spell on our warrior. Our black mage continues to blast offensive spells away, not needed enhancements to do decent damage, especially against several enemies at once. Meanwhile, our warriors becomes a lawnmower, shredding through bosses and other monsters like dry grass.

So while our decision making process never really changed, we did make some interesting decisions that allowed us to clear the game, so that’s good. On the other hand, the presence of a certain mechanic I dread really accentuates the repetitiveness – that being random encounter system. In the overworld, the player character moves across terrain divided into tiles on a grid. Each time they pass a tile, there is a chance they will be forced into a monster encounter. I think I’ve decided by now I pretty much detest random encounters, for a number of reasons. They introduce a level of abstraction that is irritating to me, bringing me out of the fantasy of the world. Where are all these monsters coming from? Where are they hiding? Why are they not dangerous until they are on top of me? Worse than that it bring an unjustified level of agency away from the player. The use of random encounters in early RPGs almost certainly was partially a tech consideration. The NES can only render so many items on screen, and a consistent supply of enemies to fight was needed. Still, from a purely ludic standpoint it’s annoying as hell. Crossing a continent in this game could take two minutes, or two hours, depending on your real-world luck stat. Mine is very very low.

I always find myself comparing old RPGs with random encounters to one of my favorite RPG – Chrono Trigger which, contrary to many of its contemporaries, had no random encounters. Enemies were consistently visible in the overworld. Sure, there were surprise encounters, and required encounters. Enemies often leap out of bushes to ambush the heroes. The added context and predictability of these encounters make them far more tolerable, especially when backtracking through areas, as is often required in RPGs. When one can mentally prepare for exactly how long a task it’s going to take, it’s a lot more pleasant than getting surprised with a lot of meaningless activity that does little but waste time. Any advantages you could gain by having random encounters can be achieved with more bespoke, designed encounters, with none of the frustration. But, this is Final Fantasy I of 16, so I’d better get used to them. Just wanted to throw out the random encounters rant early on here.

There’s one more thing I’ve got to say about this first game. Final Fantasy I sprang forth about a year after the release of watershed title Dragon Quest, itself inspired by similar role-playing-type games like Ultima. Ultima, in turn was inspired by Dungeons & Dragons, itself inspired by other tabletop war games and major fantasy works like The Lord of The Rings. J.R.R. Tolkien’s Legendarium, which includes The Lord of The Rings, represents a sort of fictive mythologized history of the real world – a legend for the modern age. My point is, Final Fantasy represents a lineage of people exploring the nature of the world as they understand it through imagination. There’s something poetic, I think, about how the heroes of the story embark on a journey that brings them across the world, and to the edge of history, only to rid the world of evil, at the cost of forever leaving those fantastical events behind, as nothing more than a fantasy. They don’t get to stay in that world, but the memory of it stays forever with them. Final Fantasy I is a humble game, with systems, gameplay, and storytelling that are primitive by today’s standards, but it’s also impossible to divorce it from all this context of its creation. There’s a lot of beauty, in this humble little adventure.

Final Fantasy II – Experiments Are Educational, But Not Always Fun

The early Final Fantasy series was notoriously mislabeled in the west under its English releases, with Final Fantasy IV being erroneously christened Final Fantasy II to English speakers because the actual second and third entries to the franchise were simply not released outside of Japan. You know, I believe in the dissemination and availability of media across cultural boundaries. Translations and localization with easy availability are not only good, but necessary for a thriving and robust culture. That said… I think I could see how The Powers That Be found that, in the project of bringing Final Fantasy to the western market… I understand why they decided, “eh, think we can skip this one” (this is a joke). I mean… It’s bad, guys. I did not thoroughly enjoy my time playing Final Fantasy II.

The story of this game is alarmingly Star Wars. I know that’s an easy criticism to levy at a lot of fantasy media, but it’s really true in this case, I think. Everything from a rebellion lead by a princess fighting an evil empire, to a secretive emperor with a flying super weapon that razes civilizations, accompanied by a right-hand man dressed in black who is a secret lost family member that eventually turns good again at the last minute. The biggest major departure is the journey’s terminus taking place in a bright technicolor version of hell, which was a pretty delightful surprise, though somewhat harsh on my eyeballs.

Okay, never mind this story is Kino.

Once upon a time, the coolest, hypest, most exciting RPG on the horizon was the as yet unreleased Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim. We were dazzled with its cutting edge graphics in one-thousand-and-eighty-whole-p, 1080p! We were told about many of its new, innovative, never-before-seen gameplay systems that would upend what we thought an RPG could be! For example, the traditional RPG character level system? Out the window! Replaced, with this shiny novel skill system where your hero would improve specifically at the tasks they performed the most. How fresh! How new! Except, of course, this system predates Skyrim by more than two decades. It exists, in near identical fashion, in Final Fantasy II, which also forgoes its predecessor’s level system in favor of an adaptive skill system. Suffice to say, it leads to many of the same problems that plagued Skyrim in its day, though in some cases to a far greater degree.

Oh featureless black void in which all fights take place, we’re really in it now…

Your heroes’ efficacy with a sword, with a shield, even with their ability to sustain damage is all determined by individual numeric values that only increase when engaged in their associated property. For your Warriors of Light to have a decent health pool, they have to be smacked in the face, repeatedly, and at length. Because you are able to target allies with offensive commands in battle, the best way to train hp is to have your heroes smack each other. The adaptive skill system introduces all kinds of bizarre and irritating behaviors like this. Whenever you get a new spell, you are not enthralled by the exciting new possibilities, but debilitated by the crushing knowledge that you’ll have to spend hours mindlessly blasting weaker monsters to get this new spell to even reach the point of being partially usable.

You will consistently feel pigeon-holed by the choices in character building presented in this game. Make no mistake, Final Fantasy II offers a bevy of options when building your heroes for battle. There are lots of different swords with different properties, from swords, to axes, to polearms. You can even dual wield! You can carry a shield. You can practice black magic and white magic as you please! You can customize your spell loadout. And yet. It takes so much time, and so much effort, to get any of those aforementioned options up to a level of usefulness with the adaptive skill system, that if you don’t choose your course for each hero early on, and stick with it, you’ll find your jacks-of-all-trades to be rather useless in combat by the end. In this way, Final Fantasy II rather lacks the adaptability in hero roster customization that even Final Fantasy I had.

This is not to say that such a level of adaptability is necessary to even complete this slog of a game. And I don’t use that word lightly. A lot of RPGs are very long, and very repetitive, but engaging with II‘s content is so consistently irritating, with more random encounters than ever before, that I eventually found myself engaging in… the Teleport spam. You see, Teleport is one of those spells – the kind that remove enemies entirely from battle. Usually, the tradeoff for that in most RPGs is that enemies will not drop loot, or provide experience points to level up. However, my hero’s skill at successfully casting Teleport did improve every time they used it, making this spell an infinite feedback loop of instantly killing everything, and becoming more likely to instantly kill everything. Including bosses! Including the last boss, save for his… very very super last, final form. Even then, we moved on to employing some other similarly cheesy strategy to dispatch him. ‘Cheesy’ in the case meaning, that it does not feel as though the strategy meaningfully engages with the mechanics of the game. The win against the boss at the end rang kind of hollow for me.

So Final Fantasy II was extremely experimental. It tried a totally new way to conceptualize character building. Even its Star Wars-ass story feels like a test bed for what these games could be capable of narratively. I mean certainly a lot of things happen in this game. It’s turn of event after turn of event, even if they all feel very familiar. Gameplay seems to have become even more simplified since the first game, but that may also be a byproduct of experimentation, with new spells and skills and whatnot. Experimentation isn’t a bad thing though, even if it seems to have thoroughly ruined this particular outing. Based on what I know of Final Fantasy now, it’s almost certain that the developers learned a lot about what worked and what didn’t while making this game, and that’ll serve them well in future titles.

Final Fantasy III – Why This Game And Not Any Other?

Final Fantasy III starts introducing more of those bizarre, esoteric concepts that require some serious thinking to really keep straight it your head. There’s no time travel, as far as I can tell, but there are larger than life mythological wizards, with special gifts of immortality, or dream walking, etc. There is global time stoppage, though. There’s a giant floating continent that the heroes were born on, not knowing it was a small part of the larger world. To the game’s credit, I also experienced that same emotional journey – and I’m sure that was the intent, a surprise reveal for players of the smaller Final Fantasy games that came before. Surprise! The game’s world is actually way larger than you thought. Pretty cool. The Warriors of (The) Light are still mostly hollow player-inserts, the quest is still to collect a bunch of magic rocks, and most characters present are not terribly deep or engrossing. The villain is once again preoccupied with immortality, and entangles themselves with dark forces beyond them for their hubris. The series is establishing its pattern of repeating narrative motifs – which is not necessarily a bad thing!

Final Fantasy III introduces the Jobs system. The seeds of this system will germ and survive long into Final Fantasy‘s future, up to present day. It is, in essence, the ability to swap your Warrior of Light’s class and associated abilities or on the fly, or under certain circumstances. In III, this circumstance is any time outside of battle. Your choice of jobs to pick from expands as you progress through the game, with more powerful ones coming later. This is pretty exciting, and does enhance the possibilities of team building from the first game. You don’t have to commit to a team right away. There are a couple problems with this first run at the system, though. For some reason, swapping jobs makes the swapped hero weakened for several battles. I say ‘for some reason’, but it’s likely to make committing to specific jobs per hero attractive, so heroes build more of a gameplay identity, rather than faceless fighters who can do all things at all times. I suspect this, because future such jobs systems will be designed toward that end, but usually in a more clever and less frictional way.

All that said though, yeah, the jobs system is cool.

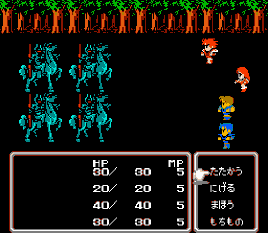

Boss and enemy design of Final Fantasy III is once again fairly simplistic, but there was a moment that came late in the game. I think what I saw in Final Fantasy III was a spark, a flicker, a momentary glimmer in the night that reminds me of the reason that I actively seek out games with turn-based combat. I’m not talking about why I play JRPGS, a vague collection of aesthetic and ludic conventions that form a genre. I’m talking about why I enjoy the play of commanding a team and managing resources in a turn-oriented fashion the way Final Fantasy does it, divorced from all aesthetic and narrative trappings. Within the optional dungeon of Eureka, I saw the essence of what makes turn-based RPGs worth the effort.

The bosses of Eureka are tough. They threaten the Warriors of The Light with devastating attacks and powerful spells. Instant death for individual heroes is a very real possibility. To defeat these bosses, my own team of heroes – us nerds playing the game, had to put our heads together and reason out a strategy. A lot of games require this kind of creative thinking – where your initial approach is brick-walled by an impassible obstacle, and a different approach is required to progress. However, given the strictly governed rules of a turn-based game, the player’s ability to think laterally and solve abstract problems is something unique to this kind of play. It’s the same sort of thing that’s made activities like Chess and Go among the most enduring of all designed games. In hundreds of hours across three games of mowing down group of monsters, after group of monsters, boss after boss, villain after villain, mostly just by spamming our most powerful moves over and over again or… gods save me… spamming the Teleport spell, Final Fantasy III, in it’s final hours, at last forced us to think. It wasn’t just that we could think creatively to solve a problem, but that the game responded to this, and rewarded this. When creative application of game mechanics leads to interesting and rewarding, designed scenarios, that, to me, is strategic liberty, the very reason turn-based games are compelling to me.

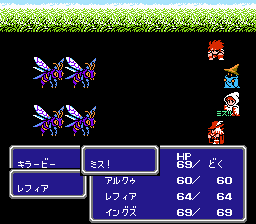

You kill an awful lot of wildlife in RPGs, I’m realizing…

It’s so important for a game to recognize its own worth. Why play this game, and not any other? I play action games to feel a sense of dexterity in my hands and tension in my heart that isn’t possible or quite the same in other formats. I play rhythm games because my sense of music aligns with my sense of play, and the two complement each other. I play platform games because the ease of traversal they entail appeals to a sense of exploration and adventure. I think often games will replicate certain mechanics or conventions based on precedent, without stopping to recognize why those things are precedent in the first place. This is the kind of thing I was hoping to see, playing Final Fantasy as a retrospective – these important core principles to the turn-based RPG and JRPG traditions develop before my eyes in real-time.

It occurred to me that the strategic liberty I so value in turn-based RPGs is much like the solving of a very elaborate and very particular kind of puzzle. It isn’t just that we had to think creatively with the tools we were given, but that the tools we were given operated in tandem to produce new possibilities. For example, the Warrior of Light Refia was our dragoon hero, or spearman. She was also our greatest damage dealer. We were fighting a boss whose physical attacks devastated the heroes. We could counter this with the Protect spell, but that Protect spell could only target one hero per turn, and only two of our heroes were capable of casting it. Moreover, each of our four heroes served an essential role in the party. Refia brought the damage, the dark knight Ingus was the only one who could take a hit, the red mage Luneth was our go-to spell caster, including caster of Protect, and the white mage Arc was needed for healing duty. Losing even one would debilitate us for the rest of the fight.

While our mages were busy casting Protect on people and not healing, one or more of our heroes might straight up die, so raising a full defense was just too slow a prospect. It occurred to us, after some experimentation, that Refia’s Jump ability – in which she jumps off screen and becomes immune to damage for one turn, then crashes back down to deal bonus damage – was maxing out the damage count at ‘9999’. Five of those jumps alone would bring the enemy down. So instead of insuring every hero could survive incoming damage, one of my friend’s suggested, let’s ensure Refia can, so she can constantly jump to safety, while busting the enemy down over the course of ten turns. Instead of Protecting the party, our mages would Protect themselves, while Refia used the guard action to survive. Then, we would buff her with Haste to ensure she’d always Jump before the enemy could act. If ever she was caught with some damage as she landed, we would repeat the process of setup, then sent her on her way to continue the attack. After a couple of tries, it worked! The enemy was defeated, and all of us players cheered.

The sense of satisfaction that washed over us was fantastic. Our friend expressed that they felt like a genius – a familiar sensation for anyone who’s played a particularly challenging RPG. It’s just a shame that this sort of thing had to take several dozens of hours of gameplay to get to. That’s a bit unfair, though, there was some strategizing that took place in the earlier levels of Final Fantasy III. However, it never reached near this level of depth. Knowledge of the game’s rules or how its various mechanics interacted was never really necessary. It was more a continuous process of experimentation – seeing what the various hero jobs did, though a feeling of utilizing them to some greater end was disappointingly infrequent.

That said, the presence of this strategic liberty, even at the eleventh hour, kind of redeemed Final Fantasy III a bit in my eyes. Like Final Fantasy I, I think it’s very commendable for its time, and it’s scratching at the surface of some of the things that I think makes this kind of game great, which is a good sign! I’m optimistic going into Final Fantasy IV, another game I’ve never played! Final Fantasy will be entering a transitional period, I predict, as it undergoes a transformation from its simple NES days to the robust cutting edge graphical and storytelling experiences of the SNES and PS1 eras, and beyond, that the series is famous for.

With the memory of their struggle buried deep in their hearts…