I must admit I have a bit of a bee in my bonnet about Sonic The Hedgehog. That was a sentence. The three-dimensional variety Sonic in particular. It is a topic I could wax about for ages, especially in light of recent promotions for the, as of this writing, still upcoming Sonic Frontiers. Promotions which have given me some thoughts. One such thought was ‘they really still haven’t brought back the spin dash’.

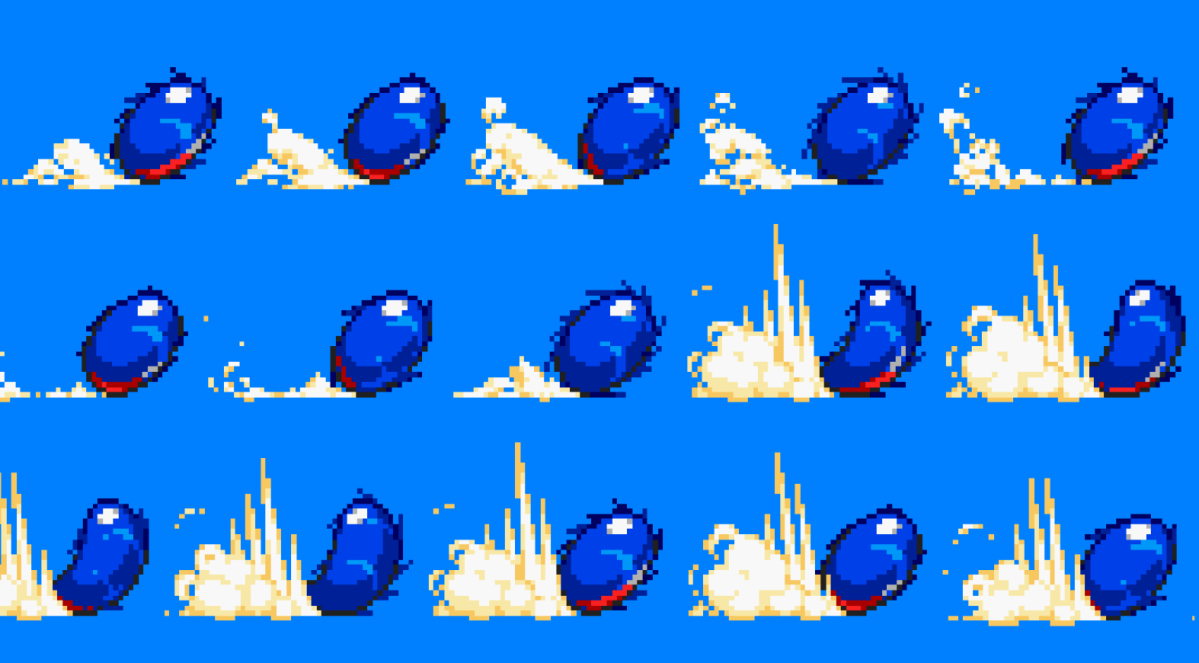

What is the spin dash? If you’ve ever heard of Sonic The Hedgehog you probably know, but it is a special move that Sonic can do by rolling into a ball and spinning to charge up energy, then launch himself real fast in one direction. Terribly simple, terribly elegant.

One of the bottomless yawning abysms which haunt discourse around Sonic as a series of mechanical systems is what values, exactly, make the games fun, and which should be the focus in a given design system. ‘Momentum’ is a word that’s thrown around a lot, and I generally agree it’s an essential component to the gameplay formula of the blue hedgehog. Building momentum is an angle Sonic has explored a lot through his games, but I’d argue that from the beginning, Sonic Team has understood that maintaining momentum is a lot more interesting than building momentum. Sonic The Hedgehog for the Sega Genesis, the debut, introduces us to the spin dash. Titular super speedy player-controlled hedgehog, Sonic is able to roll up into a ball, spin rapidly in place like the wheel of a revving race car, then take off with near-instant acceleration to a great speed. In Super Mario Bros. 3 Mario has to run a good few seconds as the player holds down the dash button to reach top speed. This requires space, it requires time, it’s generally not something you can do on a dime. Sonic Team did not want Sonic crossing long stretches while not running at super speed. The super speed is the draw after all, it’s the fun part. Ideally, the player should be given methods to reach that state of fun as readily as possible if high-paced action is the goal. Even as the spin dash fell by the wayside this value never seemed to go away. The ‘boost formula’ games, as they’re called (Sonic Unleashed, Sonic Colors, Sonic Generations, Sonic Forces), none of which feature the spin dash in the same prominence as the older games, still feature a way to rapidly build speed to a maximum level, but more on that later.

The spin dash is also a rather compelling bit of fiction. Sonic is a hedgehog, you may have heard, an animal known for rolling up into a ball to bear the quills on its back. Sonic is also super speedy, so combining these ideas creates the rather visually appealing idea of a character rolling up like a wheel in place and peeling out in a particular direction. Sonic isn’t the flash or quicksilver. He doesn’t just run fast, he rolls faster than fast. It’s one of his most distinguishing features. Mario jumps. Doom Guy shoots. Sonic rolls. The maneuver is so synonymous with Sonic that the promotional phrase “Sonic spin dashes onto the Nintendo Switch” preceded a trailer for a game in which Sonic cannot spin dash.

Or at least, I assume the spin dash is absent. As of this writing Sonic Frontiers has not shown footage of such a feature, and the move hasn’t prominently featured in a 3D Sonic game in years. At the very least this suggests it’s not very central to gameplay. It wasn’t always this way. The classic 2D Sonic games practically built its levels around its use. One of the most versatile techniques it affords by virtue of being an on-demand burst of speed is jumping out of a dash to achieve a huge amount of air time. Similarly, spin-dashing up ramps can send Sonic to great heights he cannot otherwise reach. Secrets, alternate paths, and bonuses are all available this way. The spin dash has always been a tool of exploration.

You can understand the confusion. You would think any Sonic game would prominently feature his best move. Abstractly, the spin dash is synonymous with not only Sonic but also the very act of play within the Sonic series, so foundational was it to the games’ very identity. It is like Mario’s ability to jump. Well, Sonic can jump, but likewise Mario has near-always had a dash mechanic. Nobody who scrutinizes the mechanics of games would mistake a Mario Jump™ for Sonic’s though, and likewise you could never mistake Mario’s dash for a spin dash.

Sonic’s first 3D games leaned into this angle. Jumping out of a spin dash remains a viable and valuable way to navigate levels in interesting and unconventional ways, really embodying the idea that Sonic can go anywhere. Not only that, but 3D adds the wrinkle of allowing the player to precisely plan where Sonic is going to be catapulted. During a spin dash’s charge time, Sonic is totally stationary but his rotation can be controlling for some precision maneuvers. Having a mechanic that halts movement like this may seem backward at first but it’s implementation gives more of a slingshot-like impression. It’s is more of a reorientation than a halt. Like redirecting a bolt of lightning. In combination with Adventure and Adventure 2`s character physics system, which allows momentum to carry or bounce Sonic along surfaces, the spin dash’s sudden dizzying speed can accomplish some truly magnificent feats of traversal. Manipulating and redirecting Sonic’s momentum this way is an extremely compelling game system onto itself. It adds a skill-based bit of nuance to Sonic’s kit where it was needed, as 3D Sonic has historically had to make concessions to automation in certain areas, to keep players on track when running at high speed, and thus the skill ceiling is hidden in little details like these. The spin dash is what gives Sonic’s mode of play the methods for player expression and exploration that gives a platform game its longevity. Watching any speed run of Sonic Adventure 2 will give you an idea of what I mean, like this one by Talon2461 for SGDQ.

Sonic Heroes does not feature the spin dash in name, though it does represent the first step toward eventually phasing it out of headliner Sonic games. Sonic Heroes dubs its variant of the spin dash as the rocket accel. Fancy. The differences between this version and the adventure permutations are rather pronounced. I think the big distinguishing factor for me is in the immediacy of the rocket accel, or rather… the lack thereof. Its rather slow and sluggish startup puts its use niche in a completely different category as compared to Adventure’s spin dash. The spin dash is used for precision and traversal – it interacts with the physics of each respective game such that it can be used to navigate the terrain in interesting ways. The rocket accel is by contrast mostly restricted to the ground, as jumping in Sonic Heroes heavily stymies your momentum. The mandatory ramp up time for rocket accel, which forces Sonic to move forward for its duration, makes it unwieldy and imprecise, not suited to the surgical feats of propulsion that the spin dash was capable of in Adventure. And thus, you cannot design levels for a mechanic that isn’t there, and exploration becomes de-emphasized in the games from here on out.

From there, the next iteration of the spin dash features in one of the many oddities of the Sonic series, the 2005 game Shadow The Hedgehog. Here it makes its most minor appearance to date – once again it seems as though levels are not being designed with the possibilities of the spin dash in mind, and its inclusion consequently feels almost like an afterthought. One of the advantages of the spin dash was initially the ability to launch one’s player character like a projectile to defeat enemies along a chosen path, but Shadow The Hedgehog is a game that perplexingly immerses itself in sprawling shootout scenarios, with guns everywhere. An alternative to projectiles seems rather redundant – were that the gunplay of Shadow were near as nuanced as Adventure‘s spin dash, but alas.

About the actual mechanics and physics of the Shadow spin dash, it’s back to being a little more like it was in Adventure, with a stationary startup animation and the ability to precisely turn toward your desired trajectory, although only “precise” to the level that anything in Shadow The Hedgehog could be described as “precise”. The startup for this one is terribly sluggish, however, taking up to nearly two full seconds before a full-powered spin dash can be performed. The turn rate of the startup is incredibly slow, making any “precision” you can glean from it come at the cost of something very disruptive to game flow. One of the main advantages of the spin dash is how it can be used to quickly plan a trajectory. What’s more, Shadow’s basic acceleration is so potent in this game that the spin dash isn’t really needed for quickly getting up to speed either. And finally Shadow, being built on essentially the same engine as Sonic Heroes, shares its momentum-killing jump, so the aerial utility of the spin dash is lost as well. As a child I found myself hardly ever using what used to be my favorite move in the speedster hedgehog playbook.

Sonic The Hedgehog from 2006, colloquially Sonic 06 is infamous for its disagreeable player interface and wonky movement systems, but how does its spin dash handle? Well, not great. Like everything else in this game, it is so bizarrely disconnected from every other component of Sonic’s moveset, it hardly has a use case. It is based on the Adventure mechanic, but it does not fulfill the same advantages. For one, you cannot jump while dashing out of a spin dash. The game simply will not allow it. The jump button does nothing while Sonic rolls around (at the speed of sound). Rotary function has been restored, turning Sonic while he revs up the spin is no longer painfully slow, but the dash itself doesn’t reach a particularly impressive top speed. So the poor mechanic is still missing its once great utility.

Starting with Sonic Unleashed, the series begins to de-emphasize traditional precision platforming in favor of high speed, almost race car-like tracks of long linear terrain, with a peppering of obstacles, but very little of the exploration that characterized the Adventure Games in favor of a more narrow approach. No disrespect. What these games, the “boost games” do, they do very well, usually. They’re not platform games in the same way traditional Sonic games are though, and as such the spin dash simply didn’t fit. There’s no real reason to ever stop, or sharply pivot in these games. Forward is your chief concern. They handle the maintaining of momentum in their own way. Some of the less standardized Sonic titles such as Sonic Lost World would continue to feature the spin dash, and its position in the 2D and ‘classic’ Sonic games is quite enshrined. Sonic Colors, Sonic Generations, and Sonic Forces however, essentially follow Unleashed‘s lead and decentralize the need for a spin dash in any 3D settings. They are all mechanically competent games, though focused away from certain qualities of Sonic I’d like to see return. On the other hand, it leaves Sonic the character in an odd place where he lacks one of his most memorable abilities which stylistically played off his status as a rodent that rolls into a ball. Sonic has spikes on his back, but in these boost games he mainly dispatches enemies by running headlong face-first into them. Mega Man has a cannon on his arm, so it’d be a bit odd if he never used it to shoot anything, and it’s a bit odd that while Sonic can roll into a ball and go fast, he can’t roll into a ball to go fast.

I cannot hide that the apparent lack of the spin dash in Sonic Frontiers is deeply disappointing to me. One would think, in a game that apes so much from its open world contemporaries, that interesting and nuanced methods of exploration would be a chief concern in designing Sonic’s move system for this game. The boost games don’t care much for physics-based momentum or complex acrobatics, and they seem to be the blueprint for Sonic Frontiers as well. There’s a fundamental incongruence, though, in dropping a move system designed for running down long, straight corridors into an open world map. There’s a lot that concerns me about that game to tell the truth. The spin dash in particular though was such a natural fit to the expansion of Sonic’s field of traversal to three dimensions that any iteration upon it since Sonic Adventure 2 has only served to make Sonic less suited to his environment. By the time Frontiers began development, the spin dash was so far fallen from its former importance to the hedgehog’s gameplay that I’m not sure it was even in a position to be executed well were it included. In an ‘open zone’ concept game, as they’re calling it, I cannot help but feel as though the ability to stop and start with a precision speed boost on a dime would be invaluable for a game that puts increased emphasis on exploration. “Imagine if you could just see a landscape on the horizon, and run straight there” I’d see people say day after day, every time the speculative discussion of open-world Sonic came up. That’s the appeal. Do you want to know what the Sonic game mechanic is for fulfilling such an experience? You know already it’s the spin dash. After such a long time of distancing Sonic’s more exploration-heavy roots, I had truly hoped that an open-world Sonic would reconsider the design context of this once-ubiquitous ability. Perhaps the spin dash can be unlocked in some capacity, but that still leaves it as a niche in the design, not a central defining mechanic like it used to be. Sure a regular old dash is still present, but hopefully I’ve illustrated to you why the spin dash is so much more than that.

Rolling around at the speed of sound…