Much ado has been made about the prevalence of violent combat in games, how it is a much-trodden space with an overabundance of focus on the damaging and killing of enemies in games. It’s worth interrogating how we make games and what the systems we put in place represent. ‘Combat’, as a gameplay system takes the form of abstract tasks meant to represent a conflict. Conflict doesn’t have to be violent, or even involve fighting. When you think about it, a lot of the standards and practices that are common for designing ‘combat’ conflict in games can be abstractly applied to a wide variety of real-world situations that don’t directly involve violence. There’s an adage that action or fight scenes in narrative is like a conversation, and I think this broadly applies to all sorts of interpersonal conflict. All this to say that Undertale takes extremely familiar RPG combat design traditions in an extremely nontraditional way to represent its conflict, which can take the form of violent struggle or extremely peaceful, yet tense conversation. I want to talk about this, in particular, the space where the bulk of Undertale‘s gameplay can be found, in the peaceful ‘pacifist’ style of playing Undertale.

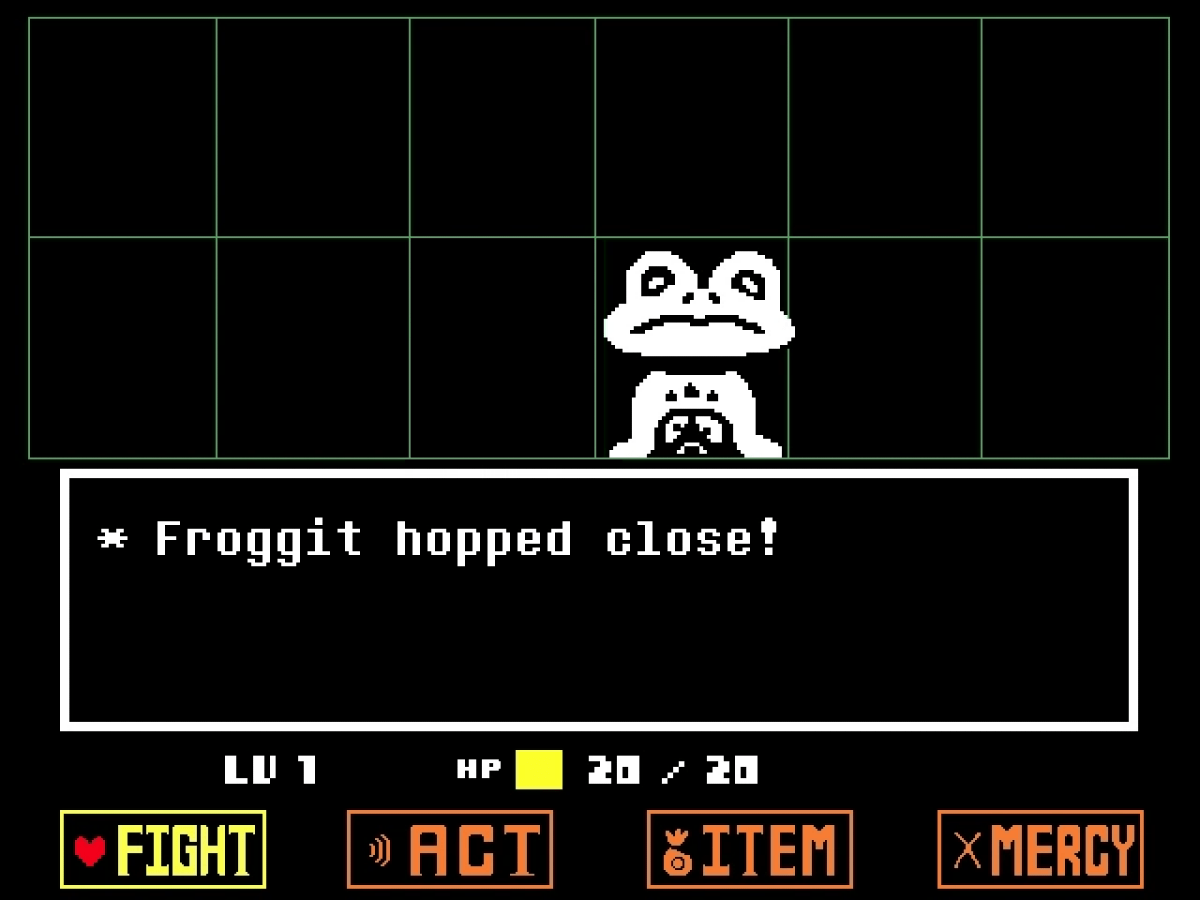

A similarly large quantity of ‘ado’ has been made of Undertale‘s underlying morality system, which allows the game to read and react to player actions across save files to drastically alter the story and how characters react. I’m sure there’s not much more I could add to that well-worn conversation, but what I don’t see talked about near as much is the actual mechanics that make up Undertale‘s combat system. Undertale is ostensibly a turn-based RPG, and it has many of the trappings you’d expect of traditional RPG combat. The player and AI take turns taking actions, there are character statistics such as health or defense, and there are the usual available actions such as attacking or fleeing. Compared to the traditional turn-based RPG formula, however, Undertale leans a lot less on strategy, which is to say forethought and formulating a plan of attack. Success in combat in Undertale is much more contingent on one’s ability to navigate enemy attacks, which take the form of ‘bullet’ patterns in a shoot em’ up or shmup styled dodging sequence. Now, that all sounds rather violent, but all this really means is the player must move around a little icon representing themselves (in this case a heart) so it doesn’t collide with any objects on screen. In this way, Undertale works to make defending, in other words passivity, a more engaging and fun mechanic than attacking. Undertale also loves to borrow from genres outside of RPGs to accomplish this, like incorporating elements of text-based adventure games.

When monsters randomly encounter the player, as they’re wont to do in RPGs, the monsters will be naturally on the defensive around you, a human, a member of the vile people that attacked and banished monsters underground. The goal for a pacifist player will be to simply exit the encounter unharmed so they can reach their next story chapter. You see, when it comes to the player’s form of ‘attack’, their agency in all of this, the problem Undertale faced was making the act of de-escalation as interesting and satisfying as the act of chopping dudes in the face with a sword. The solution to this problem was found in three ways. First, the act of defending is made into a compelling game in and of itself. Secondly, the player is given short-term and long-term goals in every encounter. Finally, the incentive for the player to not perform acts of violence is made to take the form of exploration into interesting characters.

We’ve touched on that first item. Undertale’s defense or ‘bullet hell’ sections involve dodging the magical attacks of your opponents. The conceit here is simple, but a time-tested one, utilized in tons of classic games like Galaga or Space Invaders. The player is represented by a small heart, and obstacles will move around the screen which the player has to avoid by moving freely in two dimensions. It’s among the barest, simplest forms of spacial and temporal awareness as gameplay one could think of, but that’s why it’s so effective. Some of the best games are those that start with an extremely simple base that can be built upon, and Undertale certainly builds upon it. Bullet patterns become increasingly elaborate and difficult towards the end of the game. Bullet patterns can take the form of obstacles that are abstract shapes, obstacles shaped like characters, obstacles along vector lines, any of which can move in a variety of patterns. The game will also iterate on these basic designs using new rules and wrinkles that change up the variety, such as adding gravity to the player’s avatar, a controllable shield, or a controllable projectile to destroy obstacles.

This makes up the player’s short-term goal in every combat encounter. Each turn, the player has to focus on the imminent danger of enemy bullet patterns. Lots of RPGs have incorporated real-time gameplay into turn-based actions. Integrating short-term goals like this sort of action gameplay with longer-term goals keeps the player’s attention engaged and the tension subsequently high. There will always be something in the back of your mind that you’re working toward, while immediate concerns keep you constantly engaged. In Undertale‘s case, the long-term goal for each monster encounter is trying to figure out how to make them passive, and amenable to ending their attack against the player. Each one is different, and like a little puzzle or text adventure encounter where the player has to figure out how to spare their opponents. The need for dodging enemy attacks, is essentially your payment ticket for each attempt made to pacify the opponent. A wrong answer means needing to dodge more attacks. There is some strategy in Undertale’s combat in how you approach multiple opponents. Sometimes more than one monster cannot be pacified in the same turn, so a consideration of the order in which they are tackled is added to the player’s long term goal achieving process.

The final and I think most important of how Undertale solved for nonviolent ‘combat’ is its methods of incentivizing the player. The typical pattern for any game with combat is to reward the player for killing or defeating enemies, increasing the player’s power as they accumulate more and more victories. So it is with Undertale, when you choose to kill. When sparing foes, however, the game goes out of its way to makes sure there is no direct material reward of in terms of player power. Undertale did not have to do this. In a vacuum, there’s no reason a nonviolent victory cannot reward and empower the player. In Undertale it was very important that external rewards like player ‘LV’ be tied exclusively to killing. Undertale is trying to justify its thesis of pacifism by making that path entirely implicitly motivated by narrative elements, or in other words the process of pacifism itself. ‘Not killing things can be fun too, no reward needed’ it seems to say.

The ‘bullets’ players must dodge can take a wide variety of forms from the tear drops of a depressed ghosts, to the flexing muscles of a pompous weight-lifting horse. If those sound odd to you, it’s by design. Undertale‘s first boss throws magical flames at you, but very little afterward will ever be so typical. Undertale uses the contrivance of ‘magic’, a power which monsters can use to express their emotions as power, to explore the character of the enemies you fight, as you fight them. In what other game can you expect to be attacked by the excited barks of an overstimulated puppy? These attacks are used as subtle characterization of each and every monster you encounter. The act of play is characterization in and of itself. In the world of Undertale magic is an outward expression of emotion, and this carries through gameplay as well. It’s not always a direct metaphor, and it’s often subtle, as reading emotion is in real life, but the attack conveys the emotional state of the monster which used it. You can get a sense of monster personalities just by playing. The dialogue does heavy lifting in this department as well, through hilariously absurd and weird scenarios. In this way, your ‘prize’ for victory is often a hearty joke, or an emotional catharsis. It can engender an intense curiosity to see more out of these monsters, more you won’t get to see if you kill them.

The player is ideally motivated by the desire to explore interesting and compelling characters. This, entwined with the short and long-term goals I mentioned earlier. The player’s long-term goal is usually discovering exactly how new monsters will react to their various actions. The monster Shyren loves to sing but is too timid, needing gentle encouragement from the player humming along. The monster Woshua is obsessed with washing things, so asking for a cleanup and successfully intercepting its healing water will make it very happy. The monster Aaron will become so swept up in out-flexing you if you try to match his style, that he’ll flex himself right out of combat. Keying in on visual indicators like the enemy’s emotional state, the personality in their dialogue, and the queues of their overall physical appearance all work as hints to solving the ‘puzzle’ of connecting with them socially and deescalating conflict. One can trace subtle changes in expression even, in certain encounters. The game, as it were, becomes one of determining your conversation partner’s wants and needs. It becomes a game that teaches empathy.

Combat, as it is typically designed, in all of its many forms, is fun. That’s just simply true, and it’s probably the biggest reason violent conflict remains so prevalent in games, as it’s the most obvious way to explore this form of play. This form of play was invented to represent violence, after all. Undertale is refreshing in how it explores a world where such play can be representative of all manner of other forms of conflict. Lots of conflict occurs in our daily lives every day that doesn’t end in death or grievous injury. There’s clearly a lot of space yet to explore how to adapt our design conventions to the task of representing these nonviolent forms of conflict in fun and interesting ways. I think part of the reason Undertale made such waves is that there’s a huge appetite for that as-yet only slightly explored space.

Even when you ran away, you did it with a smile…